For a distributor, when your company slogan is “Everything Under the Sun,” you better be able to deliver. But what does being able to deliver actually mean when it comes to measuring day-to-day performance? The answer to that question offers a glimpse into the lean journey of Plumbers Supply Company.

Plumbers Supply At-a-Glance

- Headquarters: Louisville, Kentucky

- 13 locations in Kentucky and Indiana

- Serves plumbing, fire protection, and HVAC contractors and industrial/institutional customers

- Employs 100 at headquarters and six to 30 at each branch

- Family-owned

Based in Louisville, Kentucky, Plumbers Supply has 13 branches in Kentucky and Indiana that stock parts and supplies for plumbing, fire protection, and HVAC contractors, as well as industrial and institutional customers and facility managers. Several years ago, with an average line-item fill rate of over 95 percent, the company’s fire protection department was achieving best-in-class performance, at least according to the standard industry benchmark. Unhappy customers, however, had a different opinion. That’s because not having four or five out of every 100 items needed for a construction project could stop them from starting or completing a job.

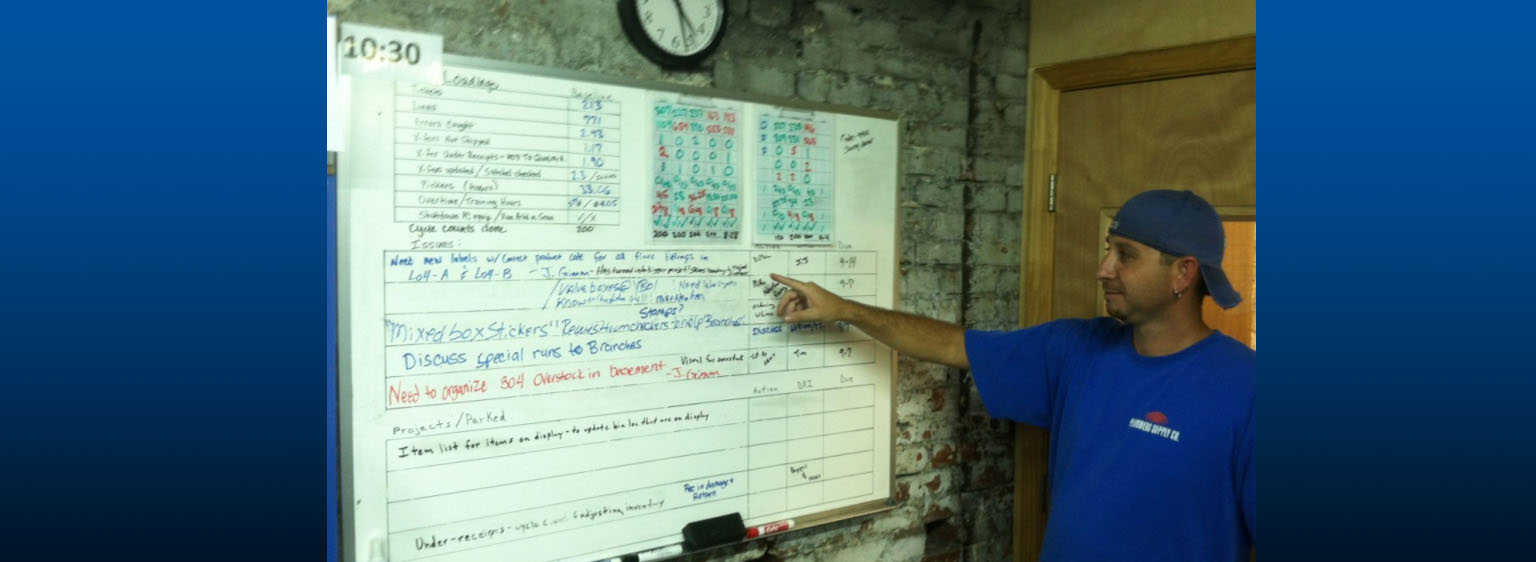

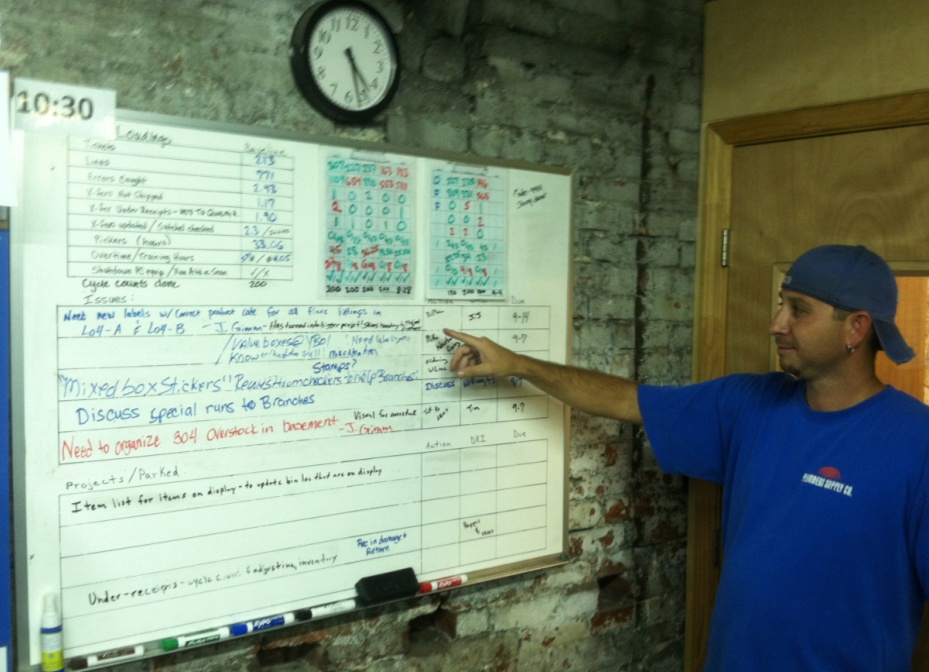

The issue came to the attention of Jay Johnson, the company’s president, during the daily management “walkabout” that he implemented two years ago at the very beginning of the company’s lean initiative. “I’d be in that department three days per week, and every day it was the same issue,” Johnson recalls.

For a month, they tracked performance on the department’s walkabout review (WAR) board, a visual management tool that the Louisville branch uses to monitor expectations, performance, and issues as they come up. “Then we completely changed how we measure service performance at the department, branch and company levels to a 100% complete order fill rate…, and we were able to focus on improving performance for particular categories of product.”

Changing to a more customer-oriented measure of order fulfillment is just one indicator of the progress Plumbers Supply has made in a relatively short time. This Lean Enterprise Institute case study explores how lean can take root and transform the performance of a small (less than 250 employees), privately-held distribution business that bears very little resemblance to the automotive assembly line typically associated with lean management.

The Building Is Paid For

The original structure at the Plumbers Supply headquarters in Louisville dates back to 1898. Expanded regularly over the years, today it’s a warren of 31 rooms and storage zones with varying weight and height restrictions spread across four levels — accessible by stairs and freight elevator — plus 11 additional storage locations outside. Here employees use shopping carts and flatbeds to pick orders for some 45,000 stock-keeping units (SKUs) — every kind of plumbing and HVAC product and part you can imagine, including a selection of identical items made in the U.S., as preferred by some customers, or imported.

After they’ve picked the orders, the company delivers some directly to job sites. Customers can also pick up their orders at a will-call drive-through or go inside to the service counter. As part of an attempt to better forecast customer demand, a historical SKU study found that some 70 percent of the company’s product demand is unpredictable. Add in some dramatic seasonal fluctuations and nightly transfer shipments between locations, and you can start to get a feel for the procurement and inventory management challenges at Plumbers Supply.

Given the physical constraints of the facility and an uncompromising commitment to customer service, when it comes to making improvements, the company has one significant advantage over larger, more corporate organizations: a strong, family-oriented culture with a flat hierarchy and accessible leaders. It employs roughly 100 people at its headquarters in Louisville and six to 30 people at each other branch location. The company and its leaders have a reputation for treating both its customers and employees with respect and promoting from within. As one manager shared during our visit, “When I was having trouble with an employee’s performance, my boss asked me how I’d manage the situation if she was my aunt, for example, because that’s how we treat people.”

A Local Source of Inspiration

So why and where would a family-owned distribution business begin its lean journey? Through a local business group, Jay Johnson became friends with Jim Lancaster, CEO and owner of Lantech. Headquartered in Louisville, Lantech manufactures and markets pallet stretch-wrapping equipment, which Jim Lancaster’s father invented in the early 1970s. LEI’s James Womack and Daniel Jones featured the company’s early lean efforts in an entire chapter of their popular book, Lean Thinking (Free Press, 1996).

The main issue in a lot of businesses is that management isn’t connected to what’s happening in the business every day.

“The place to start [with lean] in any business is where your problems are. The main issue in a lot of businesses is that management isn’t connected to what’s happening in the business every day,” said Lancaster when asked about how Plumbers Supply got started. “What you’re trying to do is make changes in the business and convert people’s thinking, and give them a successful experience.”

Walking the floor of Lantech with Jim Lancaster in 2009, Jay Johnson recalls being impressed by the work cells, material flow, and cleanliness, even though it bore little resemblance to the workflow in his distribution operation. But as they walked from one area of the factory to the next, he was really struck by how Lancaster worked with the company’s employees to address and solve problems on the spot. It wasn’t a loose, management-by-wandering-around exercise.

“When I saw the decisions being made,” says Johnson, “and the fact that Jim had the rest of the afternoon to improve and work on strategic planning [that is, all of the things he couldn’t spend as much time doing in the past because he was firefighting and getting bombarded at his desk with issues and problems], I knew the daily walk was the place to start.”

Before the daily management walkabout, with 18 direct reports, Johnson wouldn’t have a chance to talk to some people for weeks. And he devoted a good chunk of every day toward addressing all of the issues that popped up that day, he recalls. So, today, if something needs management attention, everyone knows that the president and his team will be there later that day or tomorrow; they will be able to see the issue for themselves firsthand and address it.

“I’ve gone from having 10 to 20 gotta-minute meetings a day, to a one-and-a-half hour walkabout, with opportunities to see what’s going on, to see the gaps, and provide coaching then and there,” Johnson says.

Depending upon who’s on-site, the daily walkabout includes the president, operations manager, and CFO visiting each functional area of the business. The walks were awkward in the beginning, Johnson reports, and it took some time to get the cadence down. People often used the opportunity to point the finger at failures in other departments. However, over time the focus on process failures and improving the process, not what any individual might have done wrong, has slowly changed the culture. Everyone is less worried about defending their turf, says Johnson, and is even excited about fixing what’s wrong and improving the business.

“It takes guts for a company leader to do this, and to be ok with making mistakes,” Lancaster adds. “It’s not always where people think a CEO should be spending time.”

The Golden Triangle

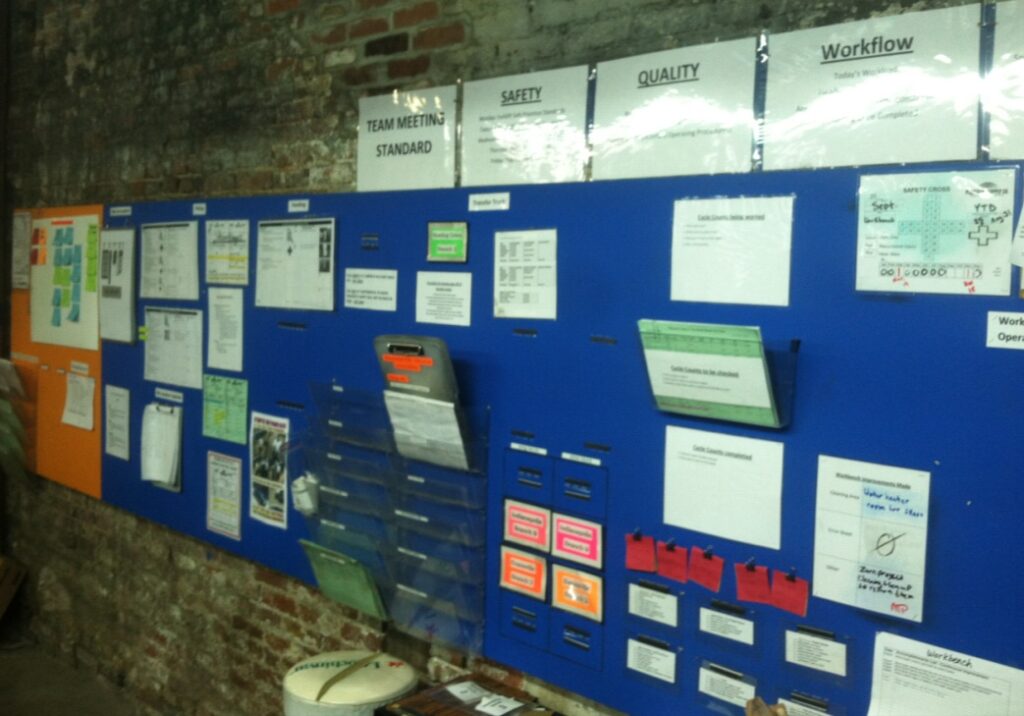

The daily walkabout spotlighted some of the opportunities and barriers for improving service quality, which has always been the number one goal of the lean initiatives at Plumbers Supply. These opportunities included multiple handoffs, excessive travel and handling, and poor coordination between departments.

“There are differences between mapping a rack and pinion gear facility versus a warehousing and distribution business. They are obviously very different processes,” Johnson adds. “That’s been a struggle [for us], how to value-stream map our business and processes to identify the waste.”

At the same time that they began the management walks, the company introduced lean tools in an ongoing series of kaizen workshops designed to train leaders on how to use the lean tools effectively. For help, they pulled in Mike Garland, currently an independent lean consultant with 25 years of experience using lean tools to transform large and small businesses. Garland is on-site roughly one week each month, coaching and leading workshops.

For a distribution operation — or any business really — it’s important to have an experienced advisor, or “sensei,” as they are known in the lean world. In addition to teaching the fundamental principles, they can help figure out solutions when you run into a wall, says Lancaster. “It’s like anything. It’s all about depth and levels of knowledge and understanding,” he adds.

Garland’s initial focus at Plumbers Supply was helping to implement standardized work. This effort wasn’t just about documenting optimal procedures or creating checklists but incorporating visual cues within the work that indicate that it has been done — and done correctly.

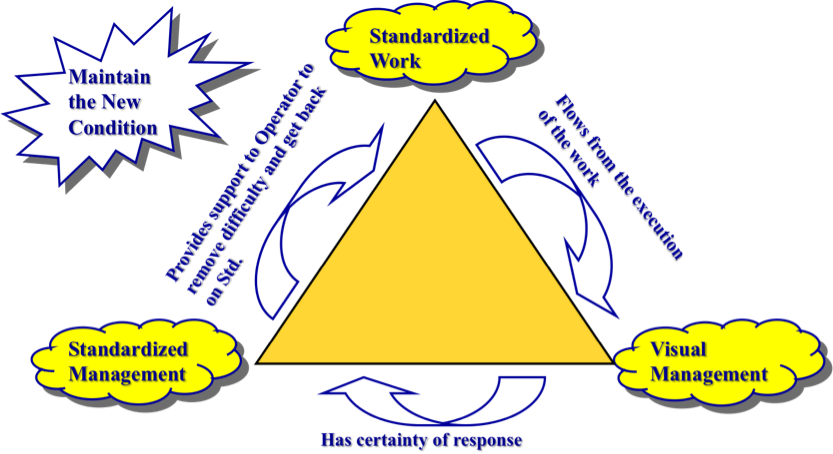

“For improvements to hold,” explains Garland, “there has to be a standard. When the standard is followed, the work itself leaves a visual signal behind so support people (team leaders, supervisors, etc.) can see that the work was done correctly. If it’s not done correctly, they don’t beat up the operator, they explore what occurred that caused the work to be done out of standard.”

Garland describes this virtuous cycle of improvement and reinforcement as the Golden Triangle (see diagram below). For example, at Plumbers, the first area where they applied the concepts and tools was—logically enough—the main point of customer value creation: the order picking process. Here standardized work has reduced the time it takes new employees to learn all the storage locations and processes and become real contributors to the organization, from six months to three weeks. In addition, the changes reduced by half the employee walking distance per day for packing and staging orders.

As John Skees, Louisville’s operation manager, states, “creating standardized work should be done alongside the employee you are trying to support and the focus should be on making their job easier.” John says that Golden-Triangle thinking allows managers to create a standard that can be built into the work environment, so it is easier to do the work correctly than to do it incorrectly. “This provides a better-quality service to our customers and a better work environment for our employees,” he adds.

The Golden Triangle: How Improvements are Maintained

Source: Mike Garland, Excellence in Lean, LLC

Leadership Skill Development

The picking process at Plumbers Supply begins and ends at the “workbench” area. This order dispatch area is the heart of the business in terms of fulfillment and has been the subject of multiple kaizen workshops. One of the process changes here, for example, was re-prioritizing the sequence of orders, which previously were cherry-picked at random, to being organized by customer priority and picking efficiency.

“People pick better and faster now,” says Shaina Smith, warehouse manager. “Before, 10 to 20 errors in a day were normal. Now, five to six picking errors is a bad day.”

In addition to the major process changes and making everything visual, including the work of supervisors, Smith stresses that making improvements is just as much about the small things as the grand design. She says the key is to do something, make some improvement, every day.

Making such incremental progress — as other companies on their lean journeys have discovered — depends in large part on how supervisors manage the people who report to them. At Plumbers Supply, that has meant a renewed understanding that the primary job of leaders, especially on the floor, is to make everyone’s job easier and safer. When something goes wrong, as Johnson puts it, they try to conduct “autopsies without blame.” Walking the floor daily gives him a better understanding of how the supervisors manage the people who report to them.

“Lean gives us the vocabulary for how we should react to problems,” he says. “Now I can see if managers are adequately supporting people and the work they need to do.”

Beyond the Warehouse

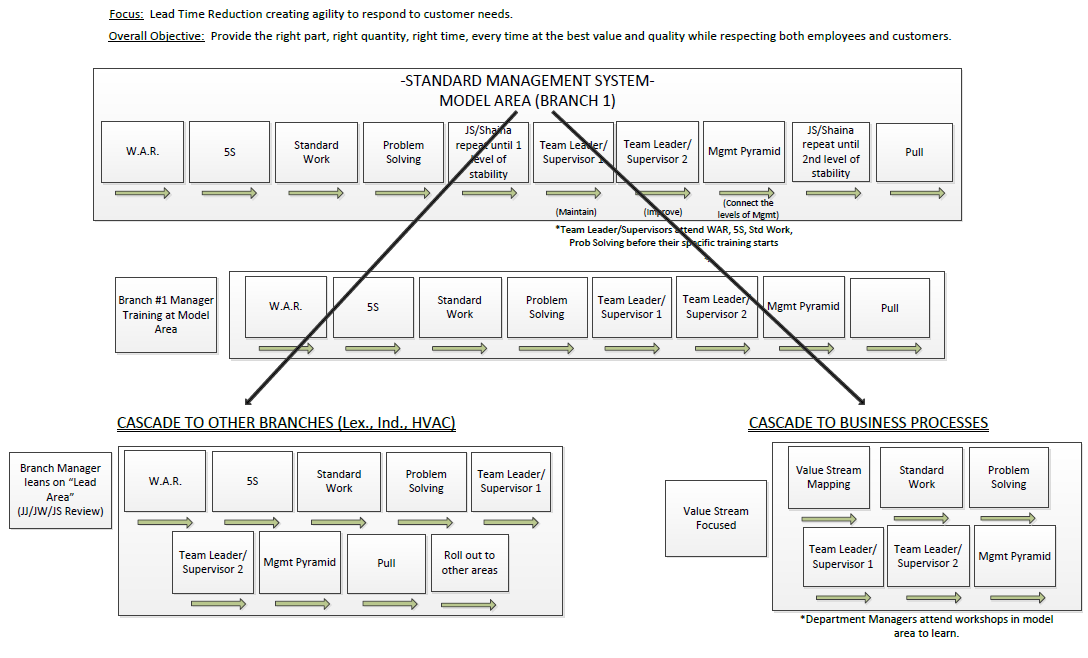

Building on the management walkabout, the lean game plan at Plumbers Supply started with performance reporting on the WAR boards and standardized work, which was soon followed by 5S practices, problem-solving methods, team leader/supervisor training, and basic pull techniques. Kaizen workshops using these tools have tackled the warehouse and administrative areas, such as accounting. For example, Melanie Leasher, the controller at the time, first applied 5S to her office to set an example.

“I had cabinets in there from the previous controller that I’d never even looked in,” she recalls.

Leasher then helped the people in her department apply 5S to their work areas. Such changes can be threatening, because they generally mess with how everyone does their work, and the visual cues—like dedicated locations for everyone’s stapler—can seem pointless. But the benefit, in this case, became immediately obvious when they had to locate an important document at the desk of an employee who was out on vacation. Because of the 5S work, it was easy to see each stage of the work. And finding the document only took a minute. Next, Leasher applied 5S to the supply room, which hadn’t had a good cleanout in decades.

Supply Closet Before 5S

Supply Closet After 5S

Concurrent with the lean-related activities, Leasher and Jay Wilson, the company’s CFO, implemented a series of process changes and improvements to the company’s accounting and finance department that, over time, eliminated much of the need for a full-time controller. As a result, her old position was eliminated, and she was promoted to director of Continuous Improvement.

“In year two of our lean effort the struggle has been having the resources and talent after kaizens are done to do some of the follow-up work and having the structure to maintain and continue the improvements that we’ve put in place,” Johnson explains. With the limited resources of a small company, the strain on managers to make improvements, maintain the gains, and keep up with all of their other responsibilities, was slowing implementation. “We were still getting things done but the speed was just not at the level that I’d like to see.”

Leasher now works full-time planning and supporting the execution of kaizen workshops, with a particular focus on developing more line leaders who can use the lean tools to make their jobs easier. This will, the thinking goes, allow them more time to make daily improvements as a regular part of their job. She will also ensure all of the follow-up work is completed and support the company’s 12 other branches as lean is more fully introduced in those locations(see the Rollout Plan below). This process, management expects, should free up even more resources the company can dedicate to supporting the transformation process across the company.

Plumbers Supply Rollout Plan

Building Momentum

So far, Plumbers Supply hasn’t tried to tie the results of its lean efforts to any specific financial metrics. Such is the luxury of a private, family-owned business. Still, margin percentages are up because of lean cost savings and more consistent pricing. Leadership knowledge and development have also benefitted from the initiative.

On the operations side, productivity has increased by over 20% as revenues have grown. In addition, with the switch from a line item to the more customer-oriented 100% complete order fill rate metric, the company now has an actionable standard that will drive further service quality improvement. Dead inventory has also been cleared out.

It’s obvious from the significant progress achieved in a relatively short time and the push into the branch locations this year that Plumbers Supply is in it for the long haul, and the gains will continue to add up. As Johnson often says, “If you can improve at a faster rate than your competition, they become irrelevant over time.

Keep learning with the Leadership Q&A with Jay Johnson, president.

Editor’s Note: This Lean Post is an updated version of an article published on November 29, 2012, one of the most popular posts about this vital lean practice.

Lean Warehousing and Distribution Operations

Improve a distribution center's efficiency, quality, safety, and space utilization.