No matter how successfully a company employs lean processes, pockets of idle inventory and barriers to flow can blend into the background of daily operations until someone points out the obvious. It’s a prolific—albeit painful—moment for many lean companies. For heavy-equipment manufacturer Vermeer, one of these moments came during an annual meeting of its industrial dealers in 2005.

“Vermeer had been on the lean journey for many years, and at the end-of-the-year dealer meetings we would talk about how lean is benefitting us, and how we can now manufacture a brush chipper in a few days from raw materials to finished good,” explains Chad Vander Wilt, manager of transportation and logistics at Vermeer (read a Q&A with Vander Wilt on sustaining lean gains). “And they sat and listened for several years, and then they said, ‘You know, you talk about how you can manufacture that brush chipper in a few days, but it takes us anywhere from 90 to 120 days to get that chipper. So how is this helping the dealers and distribution network?’

“No. 1, we found that we incentivized the dealers to order monthly even though they sold product daily. So the first thing we needed to do was to change that to tie it more closely to point-of-sale.”– Chad Vander Wilt, manager of transportation and logistics

|

“That was a great wake-up call to us that, yes, we can manufacture something quickly, but if we can’t get it to our dealers and then the end customer faster, lean is only going to get us so far. That’s when the light bulb went off.”

The light bulb became a program to plan the best way to replace batch ordering in the domestic industrial-line distribution network with replenishment. During the next two years, the Pella, Iowa-based company’s 20-plus domestic dealers would become heavily involved in the replenishment planning and, in some cases, further their own lean transformations because of it.

Today, the program has become a process that automatically triggers an order for a new piece of equipment from Vermeer’s top-selling industrial line each time a dealer closes a sale at his store.

Aligning Orders to Sales Reduces Inventory

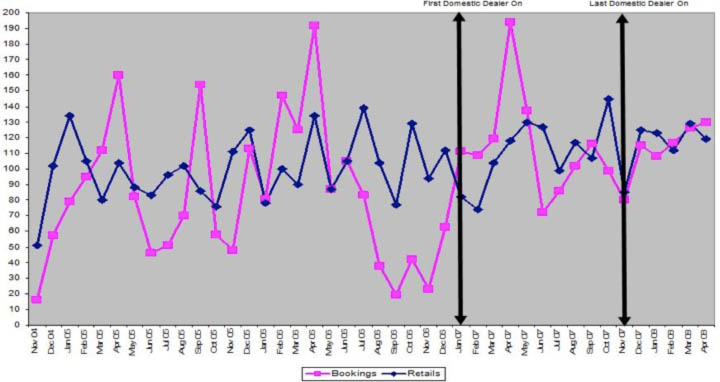

When Vermeer began putting its industrial line of equipment on pull replenishment with domestic dealers in January of 2007, the number of orders the dealers placed (pink) was widely disconnected from actual sales (blue). As more dealers started using the replenishment process, sales and orders for new equipment became more tightly aligned, which reduced inventory across the value stream: raw materials, work-in-process, and finished-goods at the dealer sites.

Source: Vermeer

Although Vermeer, a family-owned company, does not reveal current total inventory or inventory turns, the replenishment process has returned numerous quantifiable benefits to Vermeer, its dealer network, and its end customers, including:

- Cost reduction for dealers; and faster fulfillment of customer orders. Dealers estimate they spent eight to 20 hours a month placing orders manually before lean replenishment. They also would have one or two employees documenting inventory each month, which took at least one full workday. Additionally, because dealers often own multiple stores in different states, they sometimes had the right piece of equipment at the wrong location. Now they can better manage inventory to avoid this.

“If we were out of a model, we’d miss a sale,” says Stephen Farrens operations manager and partner at distributor Vermeer Heartland in Washington Courthouse, OH. “We’d do all we could to get a piece if we didn’t have it. So if a customer ordered a piece I didn’t have, first thing I would do is get on the phone and start calling other dealers to see what they had. I’m sending a guy eight hours one way and eight hours back to pick up a model—35 to 45 man hours to get the right inventory in the right place.”

If a desired model was not within Farrens’ inventory, he might have to wait as long as 120 days to fill the order, close the sale, and receive payment. And then Vermeer would not know about the sale until if and when the buyer mailed in a registration card.

- Improved cash flow for Vermeer and its dealers. Farrens says before replenishment, he would keep three-to-four turns of a piece of equipment on hand. So if he sold 12 brush chippers a year on average, he would keep three to four in his yards. He no longer needs to do this because with replenishment, he’s assured Vermeer will deliver a replacement after a sale within 30 days; and in reality, that delivery comes much sooner, often in fewer than 10 days. This frees up cash for dealers and provides fresher goods for customers faster. Dealers say it has helped them to remain competitive as one of many ways to control costs.

Inventory Reduction: Key to Sustainable Growth

Vander Wilt says once the dealer side of the process was working, Vermeer funneled the heightened visibility provided by replenishment upstream to its supply chain, so it is ordering in quantities and frequencies more closely matched to demand; and it was able to streamline transportation and logistics for all domestic finished goods by combining the delivery of its industrial line products with delivery of its forage line. This gets all finished goods to market faster and controls costs by maximizing loads.

“We have less inventory in our entire value stream for these products, and the inventory for these products turns much faster than our other products,” Vander Wilt says. “These are our A products, our highest volume and most consistently manufactured in terms of their configuration.”

Vermeer uses policy deployment to identify performance goals five-years out and then cascade those goals down and across its operations through daily problem solving and continuous-improvement projects at all levels and functions. Lean tools and language are omnipresent across Vermeer, and all new employees learn about lean as part of their training. Some of the company’s process-improvement goals focus on traditional challenges, such as doing things faster or at higher quality levels. But Vermeer uses lean principles in nearly every effort it undertakes, including such things as increasing recycling efforts, running an employee-wellness program, and cross-training for language and international culture skills.

CEO Mary Andringa has never lost focus on inventory reduction, though. It’s what caught her attention more than 15 years ago when she introduced lean to Vermeer.

“In the ’90s we were growing the business, but I started looking at how much inventory we were running, and how many people we were adding. For every 10 percent of growth, we grew 7 percent in inventory and 7 percent in people. That’s not sustainable.”

The company reversed course and began using a “creativity-before-capital” approach to growth, which continues today. Before solving a problem with an outside investment, team members look for the solution internally through observation, planning, experimentation, and execution. The formula has worked well: From 2006 to 2011, Vermeer doubled inventory turns—after 10 years of already using lean principles to drastically reduce inventory and improve efficiency.

“Lean has enabled us to acquire new product lines and manufacturing facilities,” Andringa says. “This gives us growth opportunities in more markets. By continuing to reduce various kinds of waste, we also reduce costs. These cost reductions have helped to counteract some of the inflation, wage and benefit increases, and especially material cost increases. But I continue to believe that one of the most important benefits is improving the balance sheet by being able to reduce inventory and increase cash, which can then be used for more value-added opportunities.”

First Step toward Replenishment: Observing and Learning

After the “ah-ha” moment at the 2005 dealer meeting, Vermeer began doing exactly what a lean company should: talking to its customers—the dealers —about what was happening.

“No. 1, we found that we incentivized the dealers to order monthly even though they sold product daily,” Vander Wilt says. “So the first thing we needed to do was to change that to tie it more closely to point-of-sale. The second thing we found was that there was no correlation between a dealer selling a piece of equipment and placing an order for another piece of that equipment. The third thing we found was that as soon as something like a hurricane brewing on the East Coast hit the news, our dealers on the West Coast would start placing orders because they knew that if they didn’t have their name on a spot, they wouldn’t be able to get [brush] chippers for a while because of the hurricane. So we would have a backlog of orders even though there was no real demand.”

Internally, the monthly batch ordering and panic buying would feed into Vermeer’s MRP system, driving materials replenishment from the supply chain that was disconnected from true demand. On the other end of production, the domestic industrial dealers had to manage their own shipments, and so their major transportation-and-logistics goal was keeping costs down by managing load sizes, instead of managing at the inventory level to match demand. To make full loads, they’d sometimes order more than they needed; or other times make customers wait longer for their equipment so they could fill a load.

Once Vermeer managers had all of this documented as the current state, they held kaizen events with dealers to begin planning a future-state model of replenishment. They decided that the program would be limited to some domestic industrial-line models (about 20 out of over 100) manufactured to a uniform configuration.

|

About Vermeer The family-owned company was one of the first in the United States to introduce value-stream management, lean product design, and policy deployment at its operation, which today includes seven sites around the globe and almost 600 industrial and forage equipment dealers. According to CEO Mary Andringa, lean has made Vermeer’s growth over the past dozen years profitable and sustainable. Since 2000, Vermeer’s revenue has grown by 47%, but the company employs 10% fewer people. (This has been through attrition mainly. During the 2007-2009 recession, Vermeer had no layoffs.) Vermeer’s industrial line of equipment includes machinery used for construction, surface mining, tree care, and waste management and recycling. |

“What we did with the dealers was figure out the best configuration for each model across the network,” Vander Wilt says. “So they looked at their sales last year, and if 80 percent of the models had floatation tires, we made floatation tires standard across the U.S. and Canada. And we agreed that would be part of the standard. These are the models that if you walk into a Vermeer dealership in California or Colorado or British Columbia, you should always see them. If you want a special configuration from Vermeer, you can order that, too, but you might have to wait. If you want the standard model, you can have it today.”

The process requires each dealer to send a report on inventory to Vermeer daily (this is an automated task at most dealerships). Vander Wilt says they knew that disparate business systems across the network could be a problem because even if two dealers use the same business-management software, they use it differently. Therefore, Vermeer accepts the daily report as any type of flat file (spreadsheet, .txt file, .csv file, etc.) as long as the dealer uses Vermeer-assigned nomenclature and codes.

If a dealer’s report shows a model has been sold the previous day, a new one is ordered for the dealer. (Vermeer’s production ordering team monitors the replenishment process by tracking dealer inventory, what’s on order for the dealer, and equipment ready-to-ship or in route to the dealer. These add up to a total inventory goal. That number is what determines when production begins.) The replenishment orders are used to help forecast demand as well, so Vermeer buyers can purchase raw material in smaller lots more closely aligned to true demand.

Pull Signals and Promises

After establishing standard configuration for each model, Vermeer worked with individual dealers to set min/max levels for the models based on historic sales at their locations. These are the levels that trigger a replenishment signal in the process, and they can be adjusted at any time if a dealer’s conditions change.

Vermeer also made the promise that every order would be filled within 30 days, a purposefully conservative estimate. “We really wanted to overpromise,” Vander Wilt says. “The way it’s set up, we can replenish much faster than that, and we usually do.”

When the plan was ready for rollout, Vermeer managers chose two models to put on replenishment and started working with two to three dealers a month. They would use that month to trouble-shoot, identify potential problems, and make sure the dealers knew how to execute the system. As the program expanded to the entire domestic dealer network through 2007, more models within the industrial line were added until all 100 were on replenishment. (Models continue to be added or removed as designs are updated and as models meet sales and configurability criteria that make them good candidates for replenishment.)

Next, it made sense to review how the finished products were delivered to dealers. Vander Wilt says the company had to shift its thinking here. Vermeer’s domestic products are divided into two lines: industrial and forage. Vermeer managed transportation and logistics for the forage line only. Industrial dealers were on their own to get their orders delivered.

“We would have a half load of equipment here for a forage dealer in Oklahoma. Our industrial dealer in Oklahoma would have a half load of equipment here, too, but neither of us was shipping because our loads weren’t full. Once our industrial dealers allowed us to take over managing the freight, we could then focus on building full loads of product to all our dealers.”

The industrial dealers welcomed this change.

“Now Vermeer delivers and builds its own truck loads, and we don’t need to wait until we are ordering a full truck load,” says Kyle Pieratt, a dealer principle at Vermeer Sales Southwest Inc., which has three sites in Arizona. “Vermeer has more control and can negotiate better prices.”

Getting Buy-In from Dealers

Before the replenishment project, Vermeer had already been offering lean guidance to interested dealers. Vermeer Sales Southwest, for example, held its first lean event in 2005, spaghetti mapping of the shopfloor that revealed multiple improvement opportunities. Pieratt says today his business is much more efficient, employs visual signals in multiple functions, and has conducted business-process kaizens for warranty management, accounts payable, and materials ordering. His 35-employee company continues to hold kaizen events.

Despite lean success stories such as Pieratt’s, some dealers worried that replenishment would cause them to miss sales due to lack of inventory. As Vander Wilt actively discussed the pros and cons of replenishment across the network, Andringa was also talking to dealers and inviting them to participate. Pieratt and Farrens were eager to give it a try, and as pilot sites, helped to prove that the pros of replenishment outweighed the cons.

“Once we did replenishment for about a year, Vermeer opened it up to all dealers within the network,” Farrens says. “People were skeptical at first, but once dealers started having successes and sharing them, more dealers got involved. The buy-in has been really good. The dealers are asking for more now.”

Mother Nature conducted her own test of Vermeer’s replenishment process as Hurricane Sandy moved up the East Coast … Brush chippers were in high demand along the East Coast, but inventory across Vermeer’s domestic industrial network remained balanced

|

In October of 2012, Mother Nature conducted her own test of Vermeer’s replenishment process as Hurricane Sandy moved up the East Coast and, pushed inland by other storm fronts, caused extensive damage in states that rarely experience hurricanes. Hundreds of thousands of people were without electricity due to downed trees that took out power lines. Brush chippers were in high demand along the East Coast, but inventory across Vermeer’s domestic industrial network remained balanced.

“From the day the hurricane hit up until December 2012, we shipped well over 200 brush chippers to the affected dealers,” Vander Wilt says. “And nearly all of the other dealers not affected were able to get what they needed.”

The Start of a Lean Sales Model?

In addition to taking out cost and filling customer orders faster, the replenishment process has given Vermeer valuable knowledge that it never had before: real-time point-of-sale data—demand in as pure a measure as possible. Before replenishment, Vermeer would track sales by equipment registration cards, an inconsistent and unreliable source of sales data. A dealer could sell five units in a day, and it could take 30 days for all of the registration cards to come in.

“The best thing we learned is to let the data make the decisions for us,” Vander Wilt says. “In the past, we’d look at a lot of historical data and call up our dealers and say, What do you think is going to happen? and then base a business plan on that. Now on these models, a majority of our plan is based on what is happening today.”

Although Vermeer doesn’t officially have a “lean sales model,” replenishment has moved the sales process much closer to lean. Teaching salespeople to think differently, though, was a major challenge, Vander Wilt says.

“Our biggest challenge was not our dealer network. Our biggest challenge has been internal. For many years, our sales mindset was focused on selling to the dealers. If we needed to make a sale, we got on the phone with a dealer and offered a deal. Replenishment ties sales to the end customers, and our sales force was not used to that. But when you think about it, in the old way, we were selling dealers things they didn’t need.”

Vander Wilt says this culture change is an ongoing challenge that is being addressed by teaching sales professionals new ways of creating demand. For example, they are going on sales calls with dealers and talking to end customers about their needs. This creates demand in two ways: First, if the Vermeer representative can help the dealer close a sale on a domestic industrial model, that representative is assured an in-turn sale to the dealer because of replenishment; second, Vermeer representatives can help to identify sales opportunities on other equipment (different models or customized) that Vermeer sells.

Extended Advantage in a Global Economy

Although Vermeer’s replenishment process is limited to the industrial line and domestic dealers, it is helping Vermeer to remain competitive on a global scale. The pressures of globalization are affecting even the most localized of businesses. Having a strong, successful distribution network in its largest market for its highest-volume products helps to “level load” the competitive pressures of globalization across Vermeer’s global footprint. It also helps dealers themselves to be more competitive. Dealers can work on more sophisticated marketing and sales plans for higher-complexity Vermeer products because they now devote less time to managing standard core products.

“As dealers, we experience first-hand the pressures of remaining competitive in our maturing core markets,” Pieratt says. “We, too, must look hard internally to reduce non-value-add processes and eliminate waste to remain competitive as margin erodes. The replenishment program has enabled us to reduce our inventory footprints on core products and in turn freed up capital to deploy elsewhere.”

About Vermeer

Vermeer’s lean culture is one of the longest surviving in North America, having started in 1998.

The family-owned company was one of the first in the United States to introduce value-stream management, lean product design, and policy deployment at its operation, which today includes seven sites around the globe and almost 600 industrial and forage equipment dealers.

According to CEO Mary Andringa, lean has made Vermeer’s growth over the past dozen years profitable and sustainable. Since 2000, Vermeer’s revenue has grown by 47%, but the company employs 10% fewer people. (This has been through attrition mainly. During the 2007-2009 recession, Vermeer had no layoffs.)

Vermeer’s industrial line of equipment includes machinery used for construction, surface mining, tree care, and waste management and recycling.

Next steps for you …

- Read a Q&A with Chad Vander Wilt, manager of transportation and logistics at Vermeer on sustaining lean gains.

- Learn about applying lean concepts to sales and marketing

- Extend your lean effort to the supply chain