I recently attended a program to help me learn to see and hear nature. It reminded this factory rat of going to a workplace gemba – maybe doing a Value Stream Map, which as a first stage representation is closer to reality than more abstract cost models.

The program, called Earth-Honoring Faith, also had another purpose, learning to see and hear minority women (and others) who are usually ignored. This reminded me of the human side of Lean. Without easing a multi-generational accumulation of resentments, the disaffected cannot emotionally engage. Results oriented managers have a tough time sensing this; it’s not measureable. Leaders who do see this gravitate to a “full stakeholder” view of their company and move away from an investor-centered one.

Seeing in this way powerfully affects what we measure. Understanding what to measure is key for any lean company. In Compression Thinking, we say the following:

- Limitations on growth are multiple and interrelated

- Quality over quantity always

- Organize for economy of learning (not scale)

- Heed physical measures before monetary valuations

- Learn by scientific methods, abide by all the facts

- Think holistically, deeply, broadly, and long-term

Lean has led me to question core business models, period. But while Lean focuses on improving a company’s existing business model, in part by improving its supply chain, I’m interested in how a company can help communities of people, in all their messiness, live better while using much less.

Compression Thinking is intended to do exactly this. It is intended to cope with the world and its resources being finite. (Think of it as Lean on steroids). If doing better using far less indeed matters to us, as leaders we must ask ourselves: does our company contribute to all of us all doing better with less, or is it still part of the problem by selling more and more? Even in a service industry like healthcare, are we also encouraging more consumption?

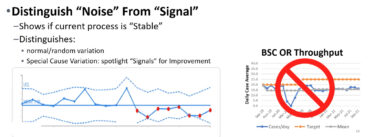

Lean relies on physical measurements. Lean accounting arose because too few cost models closely symbolize the actual flow of operations. Cost figures that do not relate to what operations leaders can see are ignored or stir up nonsense manipulating goofy numbers. However, finance and accounting issues run deeper than this:

Monetization:

The chief reason to monetize values is for market prices and for costs that promise taking in more money than we spend. But flaws inherent in monetization make costs and prices insufficient forms of learning to guide 21st century work.

- First, flaky humans assign money multipliers. The value of water depends on whether one is drowning in it or dying of thirst. Bubble busting has characterized stock markets forever.

- Second, we easily mistake symbols for reality, presuming that money is the value it represents. Money is merely a reference marker for value, both for exchange and for assessing wealth.

- Third, our confusion with symbols deepens as abstract models become more complex. For example, can traders in the heat of trading regard arcane derivative instruments that they trade as more than markers of bets on future income streams?

- Fourth, monetization confers false precision. Multiplying a rough estimate by a cost coefficient carried to six decimal places implies a certainty that does not exist.

- Fifth, monetization confers mystique, a sense of obligation because money is our reward system. But this mystique also clouds judgment. Scientists who would snicker at a sloppy non-monetized model suspend critical thinking if their rewards are at stake.

For all these reasons, we should trust physical models more than financial ones. When energy and materials have restraints on them, physical reality must guide us. Money models are just for markets, which remain necessary. Attitude is crucial. With discipline, we can regard cost margins like engineering specs, somewhat like target costing today, but not as the guiding objective. This changes everything.

No Model is Complete

This applies to all models, and financial reports are one kind of model. (Were models complete, they would be reality, not models!) We need models, including cost models, but by definition a model strips away detail. Ascertaining “truth” through these filters takes constant awareness, first that these filters exist, and second that all models have structural quirks.

Models are contextual. My cost accounting professor 50 years ago wisely refused to develop a cost estimate without knowing two things: who wants to know, and why do they want to know it? He understood that numbers have meaning only within the context within which they are interpreted, and interpretation depends on the breadth and depth of the interpreter’s external knowledge.

For example, suppose we must decide on sources of both fossil fuel and alternative energy to exploit. Return on investment models factor in markets, costs, and taxation, but may neglect physical reality. On the other hand return on energy invested (joules out versus joules in) is a consistent physical measurement with much less human subjectivity. However, return on energy depends on identifying all major steps of a total process to find and produce energy. This is not easy. Financial analyses asking only if projects pay off may deliberately “externalize” costs by omitting parts of the process.

We can hide process steps from ourselves; we can’t hide them from Mother Nature.

System Boundaries

Many issues of model incompleteness involve system boundaries. We live in a transactional economy. For nearly all organizations, not just businesses, transactional boundaries define entities for profit and loss bookkeeping. Transactions record the passage of payments in and out of these artificial boundaries – legalized fiction. Only humans pay attention to them. Nature doesn’t.

Within the rules of Generally Accepted Accounting Principle – maybe – shifting system boundaries allows us to manipulate earnings claimed. For example, shift the timing of payment recognition or hide losses in “special purpose vehicle” subsidiaries.

Fragmentation

Measurement issues take off in all directions, affecting everything. However, its key influence is that it subdivides our economy into transactional boxes, directing our vision toward the inside of these boxes. We need much more integration of thought – and operations. We assume that if everyone is making money – and more of it – surely we are better off. But are we?

It all comes back to what we see and don’t see. Our current assumptions about how to do business provide us with a limited, hobbled vision for the future that that leaves out being connected to each other and being connected to the earth that supports us all. If we think that making money is the main purpose of our company, our little box, whatever it may be (puny even if multi-billions of dollars flow into it), of course we’ll see the outside world only as something to feed our box.

I want to pose an alternative. We are tiny inhabitants of a very big universe, intent on learning more than we can ever know, including things invisible to direct vision. If we want to do right by each other and the land, we must learn to see things out of our direct line of vision. It’s time to expand our peripheral vision to see things we have formerly ignored, physical restraints and measures being just a couple of those things. In the Earth-Honoring Faith workshop I attended, this is not unlike us learning how to listen to the insights of Native American elders and of women.

So Lean is a great starting point. Lean gets you to lift-off, but to really soar you will need more life cycle analysis. Only through this kind of deeper thinking will we learn how to live well while using much less in a very different world.