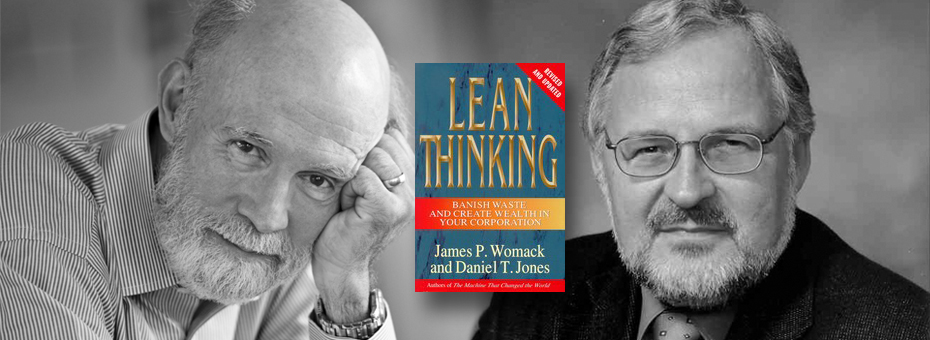

This month marks the 20th anniversary of the publication of Lean Thinking, the book that helped popularize what many of us today know as “lean.” Over the next two days on the Lean Post, authors Jim Womack and Dan Jones will discuss how their thinking has evolved since its publication. Keeping in spirit with past roundups of other lean topics, here’s a recap of the book, as well as a look at several resources giving context to this thing called lean.

Lean Thinking followed up on the influential The Machine That Changed the World, which was the first book to present a comprehensive depiction of a lean enterprise — including product design and development, coordinating the supply chain, and managing in a way that sustained the gains. As Dan Jones notes in this reflection by the two on the making of the book, “we wanted to build on the platform Machine gave us and show the opportunity for organizations to go down a different path.”

Lean Thinking accomplished this — and more. It helped launch countless corporate lean initiatives, spawned numerous lean books and consultants and further study, and laid the basis for both LEI and the Lean Global Network. Perhaps most importantly, the book established the fundamental way that many people understood and discussed lean for the years to come: as a better way to organize, manage, and above all, think about enterprise–a way of getting better outcomes (higher quality) through a more resourceful use of people, materials, finance, and more. Lean thinking “provides a way to do more and more with less and less — less human effort, less equipment, less time, and less space — while coming closer and closer to providing customers with exactly what they want,” said the authors.

Womack and Jones shaped a compelling narrative by in essence creating a villain (waste, or to use the Japanese phrase, muda), and introducing a cast of characters fighting the war on waste in the service of better value to customers.

Drawing from years of observation at the shop floors of companies such as Wiremold, Lantech, Porsche, and Pratt & Whitney, the authors showed how companies (most of them coached by consultants steeped in the Toyota Production System methods) made the lean leap from thinking to action. Today many of the characters in this book are lean legends.

It’s important to note that the ideas shared in this book are derived from close observation of actual practice. The authors were not seeking to impose a synthetic framework they invented to build a business; their work was deeply informed by their academic background, and they were building on what they had learned directly about lean and TPS by going to visit companies earnestly seeking to put these ideas to work. They sifted through what they learned and organized these findings into a simple framework for others to learn and apply. With Lean Thinking they were seeking to help people convert the concepts of lean (which were becoming well-known) into successful practice (which was uncommon then). “A lot of these lean ideas were out there but nobody knew how to do them,” says Womack.

I vividly recall reading Lean Thinking for the first time and being struck by its powerful application of what Taichi Ohno might call common sense. Unlike most popular business books, this carefully-researched resource shared a way to deliver on the promise of improvement. Womack and Jones did not exhort managers to “empower” employees vaguely nor did they shout enthusiastically about excellence. Womack and Jones codified five principles closely linked to the Toyota Production System that were adapted by the companies in the book.

The five basic principles are relatively simple:

- Specify value from the standpoint of the end customer by product family

- Identify all the steps in the value stream for each product family, eliminating those steps that do not create value

- Allow the product to flow smoothly towards the customer by arranging the value-creating steps in a tight sequence

- Create flow between process steps whenever you can and pull (not push) when you can’t

- Begin the process again and continue it until a state of perfection is reached in which perfect value is created with no waste

The book was an ambitious effort to grow the lean community by creating more lean thinkers through providing a way forward. “Our aim was to give people a license to try something new,” says Womack. Hence the 3-part structure comprised of 1) an explanation with principles, 2) examples in different industries and countries, and 3) an action plan to get folks started. Both the original and the 2003 reissue came with action plans proposing ways for people and organizations to start the lean voyage. This goal, as Womack notes in a recent column, faces the same basic challenge that all big ideas do — it takes a deep investment of time, must be undertaken at many levels, and calls for shifts not just in what people do but in what they believe:

“Lean management, which requires managers not only to change their methods but to change their fundamental ideas about what managers do…is surely not the hardest idea ever diffused but it is certainly plenty hard. Hence our steady but very slow progress.”

Today one can trace the spread of lean in countless industries around the world, in everything from healthcare to government services, from running a school to tending a farm. And while there will always be endless debate over matters such as whether “lean” is the best name for this rigorous process thinking approach, or over “inside baseball” topics of orthodoxy, it’s a great time to remember what Womack and Jones accomplished with this book:

Above all they created a language to discuss improvement, shared a set of principles (not necessarily THE method mind you) to navigate one’s course, and reported a set of examples to learn from — all in the service of giving folks a way to plan their practice; and above all to give permission to get started — what both authors frequently refer to as courage.