Photo courtesy of navy.com

The US Navy may not be recognized as a “lean” organization, and yet it was there that I began my career in lean thinking. I served as a Civil Engineer Corps (Seabee) officer and Navy diver. The Seabees have a distinguished history of process and management innovation beginning in World War II. Their rapid mobilization and construction abilities were arguably one of the more important enablers of the successful “island-hopping” strategy in the Pacific theatre. I learned a lot from being immersed in the Seabee culture.

Here are some of the things I learned:

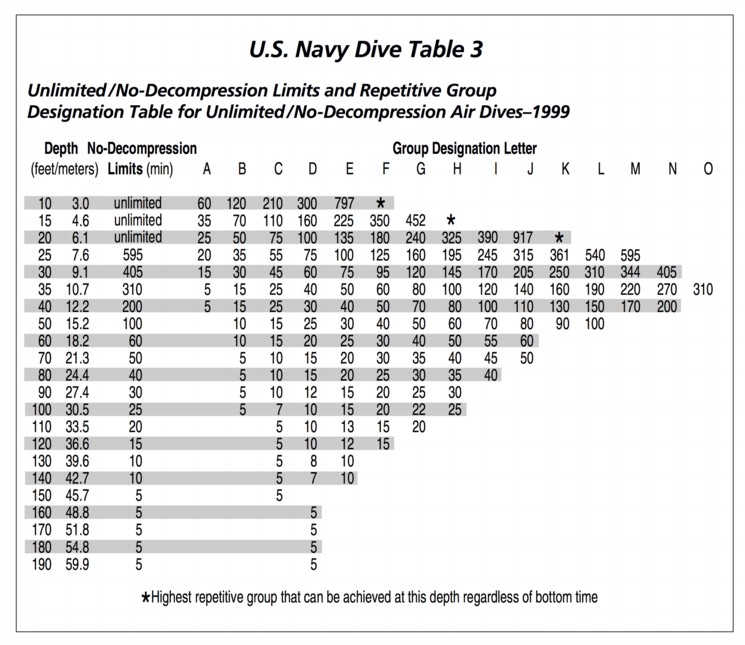

Set standards to provide stability and enable learning. Most activities in the Navy are dictated by standard operating procedures. Through blood, sweat, and tears, better ways have been found to accomplish all kinds of critical tasks that are needed for a unit to achieve its mission. There were standards for how gear and equipment was to be maintained, for how operations were to be conducted, for how people should be trained. Standards were the starting point for what to do, but they weren’t static. Sure, the learning loops may have taken longer or been a bit slower and measured than the most innovative companies in the world, but learning and evolution was a constant. Navy diving tables and procedures are a great example of this. Standards were created based on the best understanding of safe and efficient diving parameters but also with the very explicit acknowledgement that those standards were open to revision based on new information. As more information on diving operations was collected over time, the diving community would update their standards. The net result was both a stability of operations so actual results could be measured against expectations and an inevitable, never-ending march to improvements in safety and efficiency.

Set standards to provide stability and enable learning. Most activities in the Navy are dictated by standard operating procedures. Through blood, sweat, and tears, better ways have been found to accomplish all kinds of critical tasks that are needed for a unit to achieve its mission. There were standards for how gear and equipment was to be maintained, for how operations were to be conducted, for how people should be trained. Standards were the starting point for what to do, but they weren’t static. Sure, the learning loops may have taken longer or been a bit slower and measured than the most innovative companies in the world, but learning and evolution was a constant. Navy diving tables and procedures are a great example of this. Standards were created based on the best understanding of safe and efficient diving parameters but also with the very explicit acknowledgement that those standards were open to revision based on new information. As more information on diving operations was collected over time, the diving community would update their standards. The net result was both a stability of operations so actual results could be measured against expectations and an inevitable, never-ending march to improvements in safety and efficiency.

Focus on eliminating waste to achieve many different goals. Implicit in so much of my work in the Civil Engineer Corps was a focus on efficient use of limited resources and time. As part of logistics units moving thousands of tons of gear from sea to shore, time is of the essence. Bottlenecks in the supply chain can present themselves at any time. In one instance, my unit had to assemble a special pier to help the Army move their equipment ashore. Through teamwork and a relentless focus on identifying and eliminating waste in construction processes, that pier was installed in less than two weeks – quite a feat considering the massive equipment and engineering challenges involved. Our mindset was not to rush, which may have created the conditions for deadly accidents, but to create a steady flow of work with minimal waste. That was the path to safety, efficiency, and mission accomplishment. I’ve found that to be true in many business settings as well.

Respect and take care of your people above all else. Above and beyond the technical aspects of accomplishing a mission, I learned that work only gets done through motivated and skilled people. I learned that the role of a leader is to foster the conditions that allow people to understand and believe in the goals of the organization, remove or minimize motivational distractors, and attain the skills necessary to play their role well. I learned this in the most practical ways by observing the selfless leadership styles of a couple of senior enlisted men (Chief Petty Officers) in my unit. As my unit geared up for a deployment, these chiefs took extra time and care to make sure the personal matters of rag tag bunch of Seabees were in order and that their training and qualifications were up-to-date. To the extent that the purpose and details of our mission could be shared, they were diligent in communicating what people needed to hear. The net result was a unit that was at maximum readiness for its mission. And to me, these chiefs were unbelievably patient coaches – supportive of me experimenting with my own leadership style but clear about how my choices affected others. I’m grateful for the self-awareness they helped me develop.

What’s stuck most with me through those and other Navy experiences is that leadership is an energetic and selfless process.

A process of ensuring people’s basic needs are met so they can be their full, creative selves.

A process of clarifying high level goals and people’s roles in achieving those goals.

A process of coaching people and ensuring they have access to the feedback and more formal training needed to succeed and advance.

While I’m a decade removed from any formal role in the Navy and have learned so much more about lean management from leading lean thinkers and organizations, I frequently reach back to my early Navy experiences for insight and inspiration in my current lean work.