Practicing daily kaizen powerfully drives the heart of any serious lean effort to learn and improve, a topic that will be addressed in the Virtual Lean Learning Experience by several process improvement leaders from Amadeus Hospitality. This technology company serving the hospitality industry uses kaizen to push transformation from isolated projects to new sustainable ways of working daily. This includes spreading ownership of improvement down to the lowest level, and designing the work so that the process owners develop ownership of the kaizen work.

The Lean Lexicon defines kaizen as the “continuous improvement of an entire value stream or an individual process to create more value with less waste,” and notes that in Learning to See two levels of kaizen are identified:

- System or flow kaizen focusing on the overall value stream; or kaizen for management.

- Process kaizen focusing on individual processes; which is kaizen for work teams and team leaders.

It’s crucial to see kaizen as both the specific grounded efforts to continuously improve tangible work elements, and the “Adopting lean through a kaizen ‘learn-by-doing’ approach is radically different—a ‘doing’ activity as opposed to a ‘planning” activity.'” underlying managerial mindset engaging every worker in every improvement every day. Perhaps no better example of this first aspect can be found in Feeling the Gemba Magic, in which CEO Nicolas Chartier takes us along with him on a gemba walk of his company’s auto refurbishing factory.

There, Chartier compares his hypothesis about substandard quality regarding the appraisal step of evaluating used cars to sell, with that of factory manager Remi. And when the two discuss this issue with the team leader at the floor, they both discover the key flaw: nobody is managing the conditions closely—i.e. closely observing the work elements creating the observable results.

A Fundamentally Different Approach to Problem-Solving

It’s this underlying shift in mindset that is tested by consistent kaizen. As Art Byrne notes in Kaizen Learning vs. Traditional Learning, “Lean offers a fundamentally different approach to problem-solving than most traditional companies practice. It’s a ‘learn-by-doing’ method that involves the people doing the work in improving the work right now.” Conventional wisdom argues that teams formed by salaried employees who meet weekly represent the ideal approach to tackling problems. Byrne says lean companies tackle key problems immediately with a hands-on, experimental mindset. “Adopting lean through a kaizen “learn-by-doing” approach is radically different—a “doing” activity as opposed to the “planning” activity described above.”

One seldom-discussed element of this discipline is that Kaizen Means You Care, argues Dan Markovitz. He touts the benefits of starting kaizen by simply asking people doing the work to talk about what bugs them, with the aim of identifying meaningful improvement targets. He shares the story of humble efforts at one gemba, and notes: “We want people to know that they have the power to make things better and easier for themselves. We often forget that’s the real first step in establishing a culture of kaizen—just knowing that you’re allowed to improve things.”/p>

The tangible benefits of kaizen can never be understated in terms of pulling every individual into a shared purpose of improvement—a common goal that boosts results by focusing effort on clear, do-able investment efforts, notes Michael Balle in Kaizen Power. It’s also a powerful exercise in focusing finance on the right areas. “Kaizen, it turns out, is also a powerful way to identify and frame investment decisions while orienting senior leaders away from rent-seeking path of least resistance choices towards real value-seeking explorations.”/p>

Speaking of the tangible benefits from kaizen, in Kaizen or Rework, Jim Womack reminds us that the more that organizations create robust processes at the beginning, the less “kaizen”—which might better be called “rework” in many instances—is needed. Companies that demonstrate a great skill for after-the-fact kaizen, he notes, might be seen as masters of improvement. But perhaps they would have benefitted more from designing better processes at the earliest stage of development. “Was the organization’s skill in after-the-fact kaizen—that is, its talent process rework—actually reducing the pressure for hard conversations about lean process development that ought to be taking place during product development instead?” His detailed essay shares a wealth of suggestions for designing great processes upstream.

Kaizen Must Be Lived, Felt, Breathed, Seen, and Experienced

Yet one can never forget the sustained daily involvement required for effective kaizen. As Tracey Richardson argues in these two excellent Posts, a sustainable culture of problem-solving emerges when leaders are grasping the situation daily. This involves everything from going to see, to getting the solution, to getting to standard—a series of group efforts that becomes self-reinforcing over time.

It is helpful to heed Tracey’s advice closely when it comes to creating both the conditions for kaizen to occur, as well as for disciplined daily actions to succeed. “Lean has to be lived, felt, breathed, seen, and experienced. It must be reinforced by senior leaders who walk the walk and set high expectations for team members.”/p>

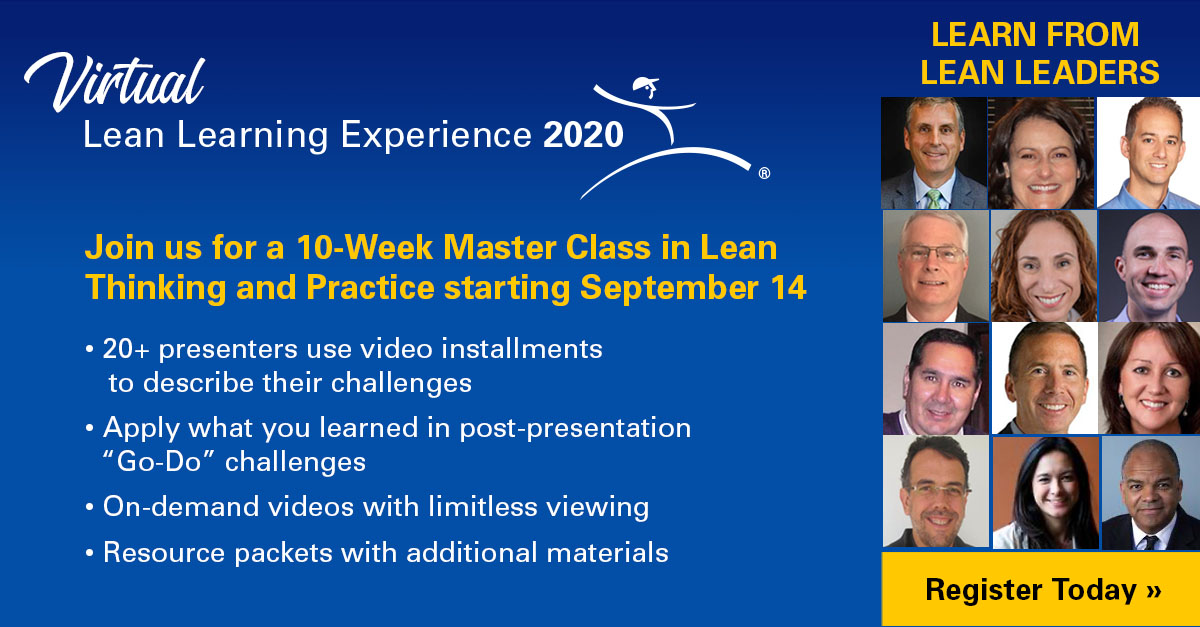

To learn more about the Virtual Lean Learning Experience (VLX), click here for details and to sign up.