I don’t like broccoli. And no matter how much “it’s good for you” prodding I get from my wife or mother (sometimes conspiring together!), broccoli never tastes any better. While eating lunch today (yep, my wife snuck broccoli into my salad again), I realized that lean thinking is often a lot like broccoli – “do it because it’s good for you.”

Whether it’s eating healthy, saving for retirement, or pursuing Lean, we are all biased towards maximizing the here and now as opposed to working towards a better future payout. Behavioral economists call this the “Present Bias” and it’s a big factor in individuals’ and companies’ resistance to change that we all bemoan.

The way I see it, we’ve got a lot work to do to make Lean simpler, easier, and more successful for the masses. There is a bias towards discussing present success (Toyota, etc.) rather than experimenting and learning our way into a better tasting future state. With that said, let me offer an example of one successful experiment in simplifying Hoshin Kanri / Strategy Deployment.

Years ago I managed a global systems business in the automotive components industry. Our company was pursuing Lean function by function, but it was up to my team to figure out how it fit in with our overall business. Each division had a balanced scorecard with 15 overall metrics and 50 functional initiatives, and each individual business was to be “managed” according to 27 different measurements. I’m sure that many of you share similar pain! So we griped for a while but then decided that we needed to try something very different. You see, an organization is a system and any system can only be optimized for 1 output. Yes, a business has more than one output, but past a reasonable point (something far less than 15 + 50 + 27), adding more metrics and initiatives confuses priorities, overburdens employees, and reduces organizational output significantly.

We decided to experiment with Hoshin Kanri to help us create and manage a more focused, efficient, and effective business planning process. In Hoshin we pick the few critical changes that will really transform our business, tie projects to those changes, engage everyone in creating achievable “Hows,” and then leverage PDCA to keep it all on track. Our model looked like this:

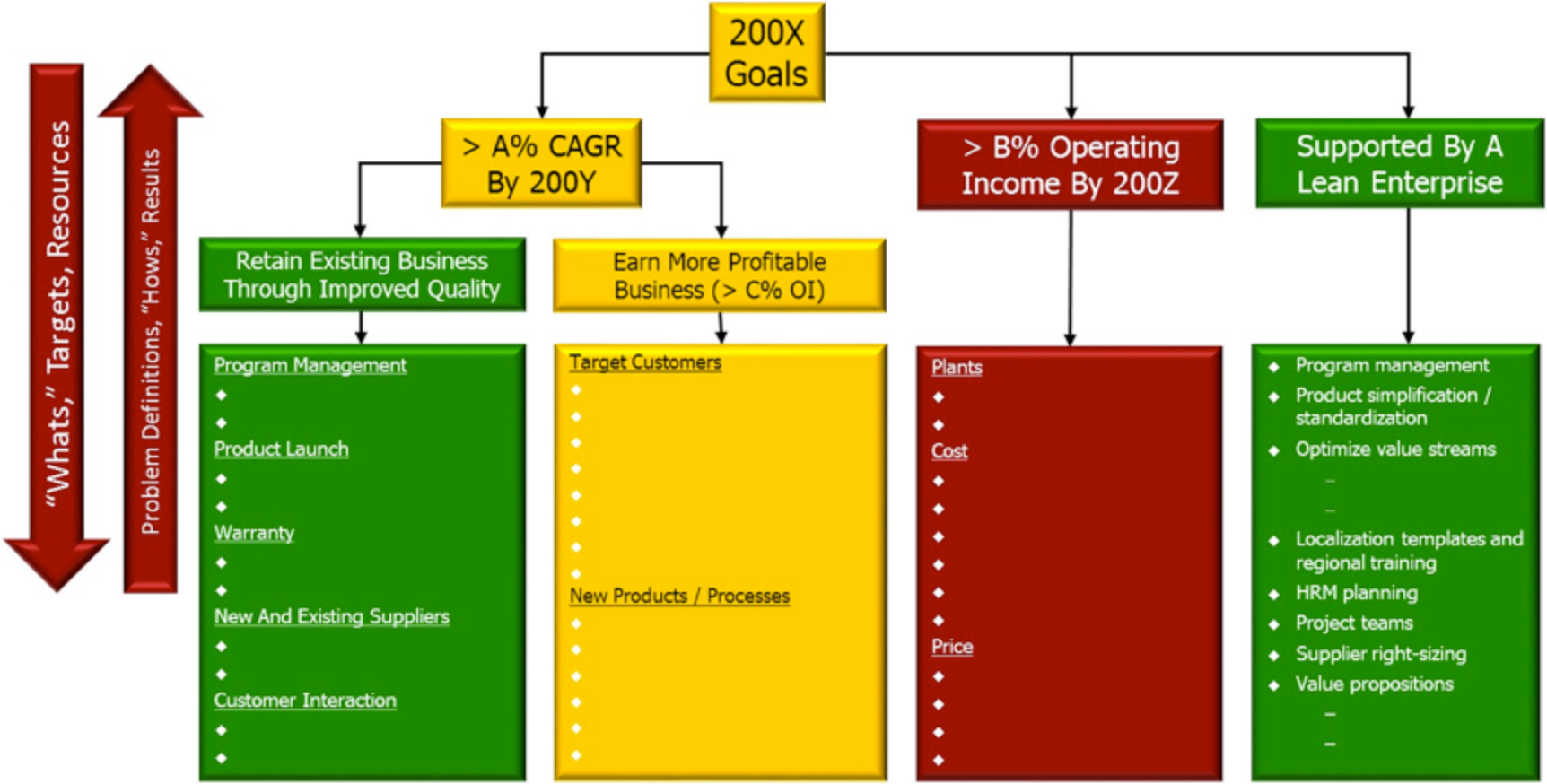

And our first business plan looked something like this (details changed):

Now before you purists have a fit that this looks nothing like the traditional Hoshin “X Matrix,” realize that our goal was not to implement Hoshin, but to create a better, 1 page business plan that everyone could point to what they were working on and readily see how it all rolled up to our shared, value stream-focused definition of success. We used colors for visual management and each project had its own A3 to further detail the exact business problem being solved.

And then came “The Great Lean Epiphany”: Success = Why + Opportunity + How Experiments

Our two major goals of growth and profit were pretty self-explanatory, but hanging “Lean Enterprise” off the end didn’t feel right. It was too focused on “doing Lean” because it was “good for us.” But then we had a major thought breakthrough: we needed to leverage Lean and whatever solutions we devised (How Experiments) to solve important (Why) and well-defined business problems (Opportunity). In doing so, we prevented Lean from becoming just another set of tasks and let it emerge uniquely to us as we went about solving our problems.

For example, we chose target customers that aligned with our particular value creation skills, and then generated specific products, processes, and value streams to support delivering that value per a necessary timeline. Lean Product Development became our solution to developing those products in ½ the time and 30% less total cost, and that led to another huge round of experiments to define what Lean Product Development had to be. We also needed lower cost / investment / volume manufacturing cells for emerging markets because that’s where the major growth opportunities were for our target customers. Rather than applying lean concepts to whatever manufacturing systems we already had, we used them to create smaller cellular concepts that required 30% less capital per unit production and could be deployed in ½ the time. Through this better focus and alignment, we were able to capture business with 10 of 10 target customers in 7 of 7 target markets, and overall, improve operating income by double digits.

Was all of that success only due to our bastardized version of Hoshin? Hardly, but it was one interconnected set of very helpful experiments for making lean concepts better support us in our particular situation. It also hanged how we approached Lean – making it simpler, easier, and therefore more useful. And in case you are wondering, I’ve changed my focus from eating broccoli as my end goal to experimenting with it as an ingredient. That made a lot of difference, too.