Be among the first to get the latest insights from LEI’s Lean Product and Process Development (LPPD) thought leaders and practitioners. This article was delivered to subscribers of The Design Brief, LEI’s newsletter devoted to improving organizations’ innovation capability. It is the first of four in a series on process development entitled “Making Things Well.”

Have you ever launched a new process only to find it riddled with old problems, either problems encountered during a previous product launch or problems that had been solved once before? In the fall of 2021, we published our book, The Power of Process: A Story of Innovative Lean Process Development. The impetus for writing it is that much of what we call “kaizen” is actually touzen1 — kaizen that should not have been necessary. In other words, engineering rework.

Process development is the work of finalizing the value stream that ultimately generates customer value. In our conclusion to better process development, we suggest “pick something and get started.” We realize that can be daunting, especially with the variety of tools and techniques that may weave together to yield a newly designed process.

In the spirit of this month’s Design Brief theme, “Making Things Well,” below we highlight nine key concepts or tips to aid in starting better process development. We wanted these tips to provide new process development insights to the reader, so we have purposely steered away from some of the basic lean concepts such as waste, standard work, etc.

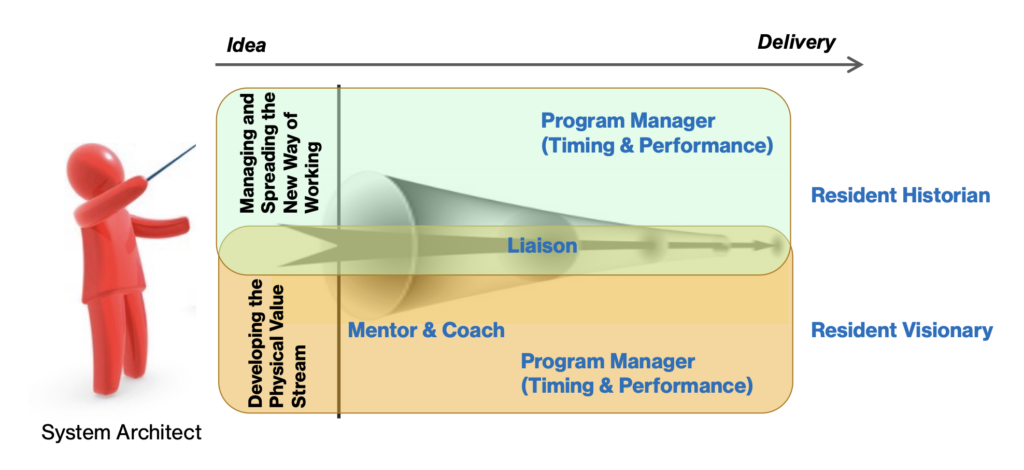

1. Appoint a system architect.

A critical early step is to find a champion or change agent to lead this new way of thinking about lean process development. The system architect must simultaneously look at the big picture of the value stream and scrutinize the details of every work element while experimenting and evaluating along the way. The system architect has two areas of focus: (1) Piloting better process development on an actual project and (2) Linking this new way of working and thinking to a management system and standardizing the work.

2. Develop a successful value stream, not merely a process.

Often, process development efforts fall short of meeting the organization’s expectations. But when development’s scope is limited to “the new line” or “the new piece of software,” poor business performance should not be surprising.

In 2007, Al Ward defined the role of development as “producing profitable operational value streams.”2 In 2019, Jim Morgan and Jeff Liker expanded the definition from profitable to successful, as defined by the organization and its stakeholders.3 The primary focus of development should be defining “good” from the perspective of all key stakeholders (customers, employees, shareholders, etc.). Then, it should design a value stream that satisfies their needs. The value stream consists of all the elements necessary to create value for the customer, including material flow, information flow, and processing.

Although the term “process development” is widely used, you need to think about value stream development.

3. Define “good” by translating the organizational needs into an operational vision.

Take the idea of a successful value stream one step further by creating a detailed vision for how it will achieve its goals. Critical assessment is vital. Are there assumptions you must declare based on operational capabilities or best practices you should utilize?

Start with proven value stream standards. Where none exist, establish them. Are supplier parts self-certified? How will you handle defects? Where will you locate inventory markets? How much inventory will be at the cell? Establish answers to such questions among others. Like any standard, if someone has a better idea, test it to see if it is truly better, resulting in an improved standard.

The system architect is responsible for creating this vision. As an analogy, consider the concept paper by the chief engineer, but focused on the value stream vision. Similar to a concept paper, much of an operational declaration’s value comes from the development, socialization, and resulting alignment around the vision.

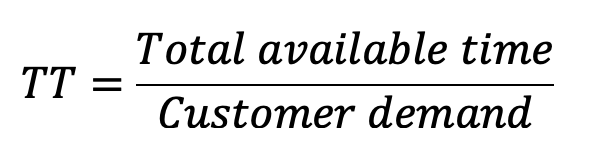

4. Manage to takt time, but do not design to it.

Okay. Calm down. We are not suggesting abandoning takt time. But for all the talk about takt time, it is still very misunderstood and misused. Most are familiar with the takt time formula:

People who develop new processes are comfortable with numbers. They think, “Take one number, divide it by another, and that new number is my target. Now get out of my way.” The problem with this thinking in process development is that neither the numerator nor denominator is clear. A new product’s demand and its process’s capability, however well planned, are unknown. So, when you calculate a takt time for designing a value stream, what are you actually targeting?

Our suggestion is to design to a natural cycle time (NCT). NCT considers the product characteristics, process knowledge, and more to suggest a least common multiple as a target for processes and work balances. You want NCT to be as low as reasonable. Let that soak in. The lower the NCT, the smaller the increments of process times you will have to mix and match to meet varying takt times. It is like having smaller Lego bricks that can be assembled into larger brick shapes versus having only large bricks that limit flexibility. Ultimately, you manage to takt time but do not hard-design processes to it because takt time is variable.

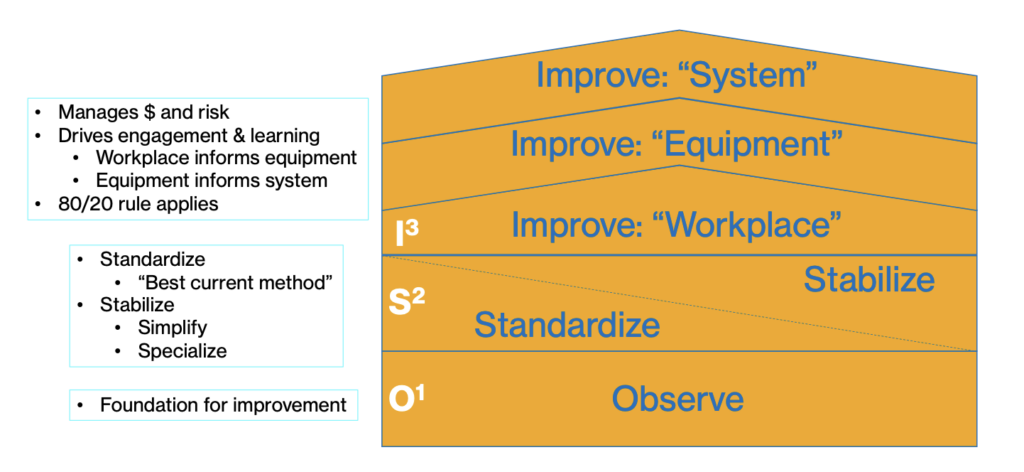

5. Put creativity before capital with O1S2I3 model.

When it comes to process development, organizations too often attempt to achieve their goals by prematurely jumping to expensive and risky solutions without understanding the basic work. Leaders commonly think success lies in new technology, machines, IT systems, or even rearranging whole facilities — the list goes on.

O1S2I3 is a simple yet powerful mental model to overcome this trap. It stands for Observe, Standardize and Stabilize, and three levels of Improvement:

- Observe the current conditions before making improvements;

- Establish a Stable Standard to create a baseline for improvement;

- Finally, start Improvements.

The improvement levels focus on methods, equipment, and the total system — in that order. This approach can help you better manage costs, risks, and lead time. Additionally, the lessons learned can inform subsequent improvements, which is especially valuable as costs and risks increase.

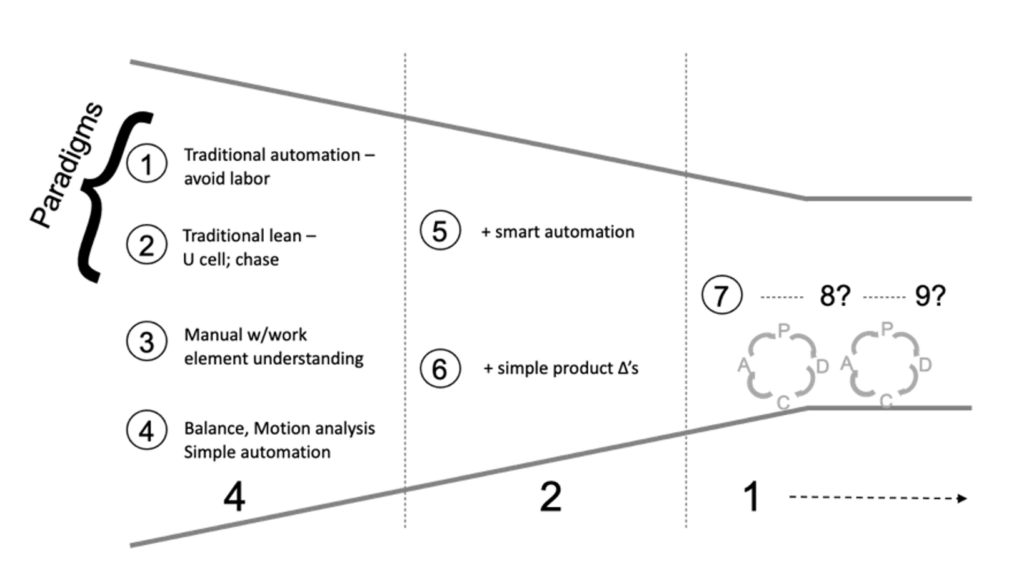

6. Explore multiple alternatives early, then converge on the best solution with a 4-2-1 approach.

Lean Product and Process Development has three basic stages: (1) upfront learning, (2) alignment around product and/or process vision, and (3) execution. During the learning phase, brainstorm multiple processing options. This forces you to break existing paradigms.

As a starting point, try developing four options, then utilize the learning to develop two new options, and so on. This is known as a 4-2-1 approach. It’s only a rule of thumb — you can start with a higher number than four. The purpose is to test several ideas at the start, converge on increasingly better designs through learning over multiple cycles, and then narrow down to the best design. Evaluating diverse ideas results in better designs than locking in and iterating on a single concept too early.

7. View automation as a tool not a goal.

If you follow tip five, O1S2I3, this may seem redundant. Nevertheless, it is important to reiterate. There are various degrees of automation. The challenge for each process is to select the appropriate degree based on your unique situation. Is it helping you achieve a quality level that is otherwise unobtainable? Are there safety issues that automation eliminates?

Automation is not inherently good or bad but should have a clear, achievable benefit.

8. Find Success (not the devil) in the details.

After aligning on a macro-level process design to meet the goals for the successful value stream, the team needs to get down to the micro-level at each step of the work. You must deeply understand details such as the individual operation motion, material flows, search patterns, and equipment motion. Once you fix the process design, you could lock in any remaining waste for the lifecycle of the product, potentially requiring large, unplanned operational spend or “touzen” to get it back to an acceptable level.

9. Complete the Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) cycle.

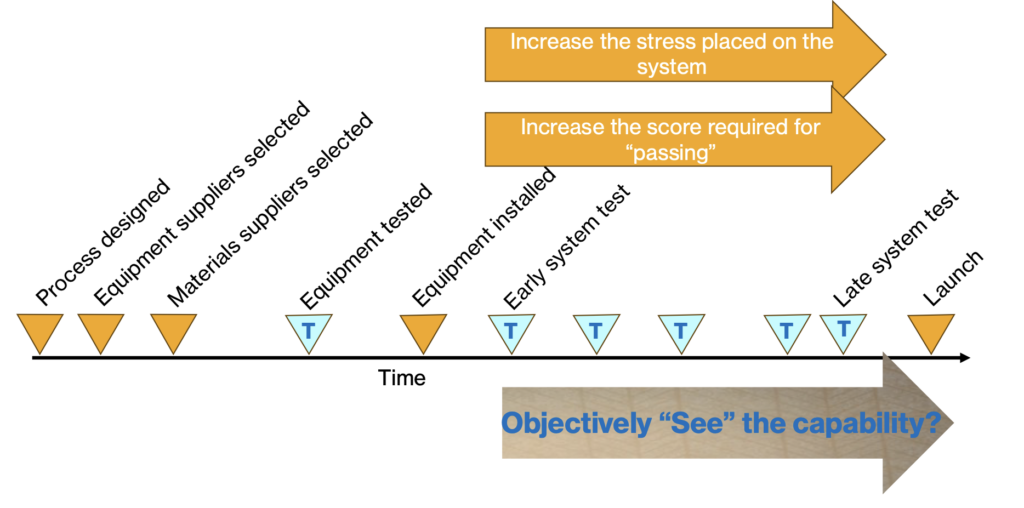

The only way to confirm that the value stream will be successful is to test and measure the entire value stream as launch approaches. You want to find the hidden problems and then learn by addressing them. To do that, you need to align on a test plan that leverages natural milestones in the development flow.

Another thing to consider when developing a test plan is to increase the stress placed on the value stream as launch approaches. An early test may run the value stream for one hour with experienced employees. A later test may run the value stream for eight hours while introducing multiple dimensions of variation (e.g., rotating employees, varying cases, parts, etc.) As you do this, you will find problems. — lots of them. That is the point. It is cheaper and easier to find the problems now versus waiting for the customer to breathe down your neck.

Unlike many lists, these tips flow sequentially. They follow a PDCA cycle, which should not be surprising, as this is Lean Process Development. Will these tips help? Yes. Do they cover everything you need to know about Lean Process Development? No. But if you pick something and get started, with a dose of humility and a desire to learn, you can swing the pendulum away from touzen and back to real kaizen with your next value stream launch.

If you’d like to learn more about improving process development, read our book, The Power of Process: A Story of Innovative Lean Process Development.

Download the latest issue of the Design Brief.

- Jim Womack, Gemba Walks (Cambridge: Lean Enterprise Institute, Inc., 2013), 73. ↩︎

- Allen C. Ward, Lean Product and Process Development (Cambridge: Lean Enterprise Institute, Inc., 2014), 10. ↩︎

- Jeffrey Liker and Jim Morgan, Designing the Future (New York: McGraw-Hill Education, 2018). ↩︎

Designing the Future

An Introduction to Lean Product and Process Development.