Part three of a seven-part series, The Real Secret to Success with the A3 Process. Learn how the A3 process is about more than problem-solving and the other facets of the practice that you should understand. Check back every two or three weeks for the next article in the series. Read the other posts:

- Part one: It is as Much a Social Process as a Technical Problem-Solving One

- Part two: PDCA is Really CA-PDCA — And it’s the CA that Makes the PD Work

_____

One of the biggest barriers to A3 problem-solving in many North American companies is that, typically, there are few if any performance measures and standards at the process level. Most companies have KPIs (Key Performance Indicators), but these are generally operational output or end-of-process measures. They also are “lagging indicators” because they show the result of the work performed but not how smoothly and efficiently the work is flowing in the process–unless they fail to achieve output KPIs. With no process or work standards, those completing the process have no way to evaluate how they are performing or where to focus problem-solving when there are problems in output results.

The situation at Toyota, where the A3 process originated, is quite different. They have a saying, “No standard; no problem,” which for them, is true. If there is a point where the company needs to measure performance to manage or improve it, they have standards for what should be happening. They have performance measures that start at the individual operation level, including defined processes and procedures. And there is tracking based on these standards that rolls up from the team to the group, area, department, operation, and company level. In the manufacturing operations area, for example, digital signs display the number of vehicles produced compared to plan at any point during a shift.

No standard may not be a problem for Toyota because they have or will create performance standards and work standards where they need them. But, for many companies I’ve worked with, that’s not the case–it is a problem, a big one. Without a standard, there is no way to see what improvements need to be made to improve performance or see the impact of changes that have been made. It’s hard to improve on a base of chaos. You can make changes, but with the confusion, disorder, and instability, how can you tell that you’re moving in the right direction? How would you know that you’re making a difference in a chaotic, unstable situation?

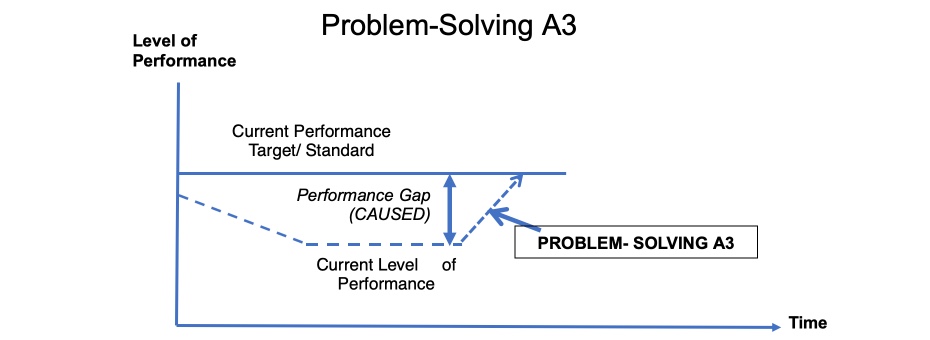

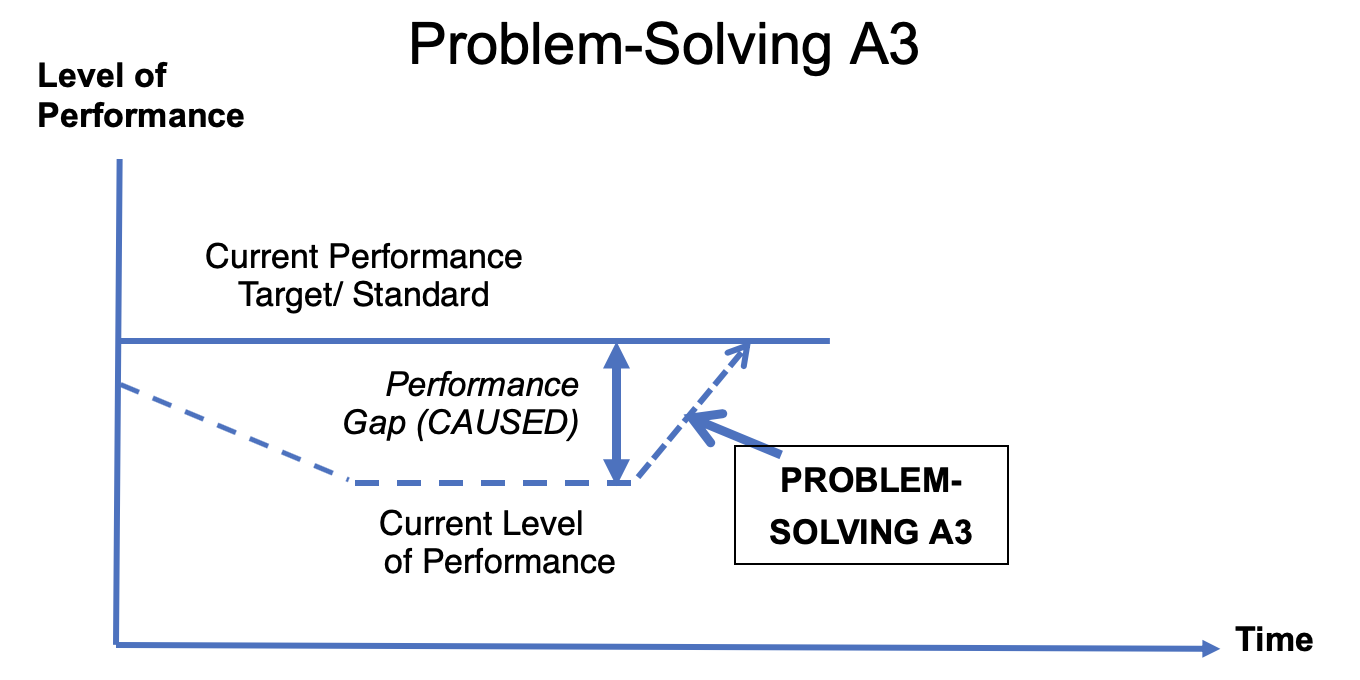

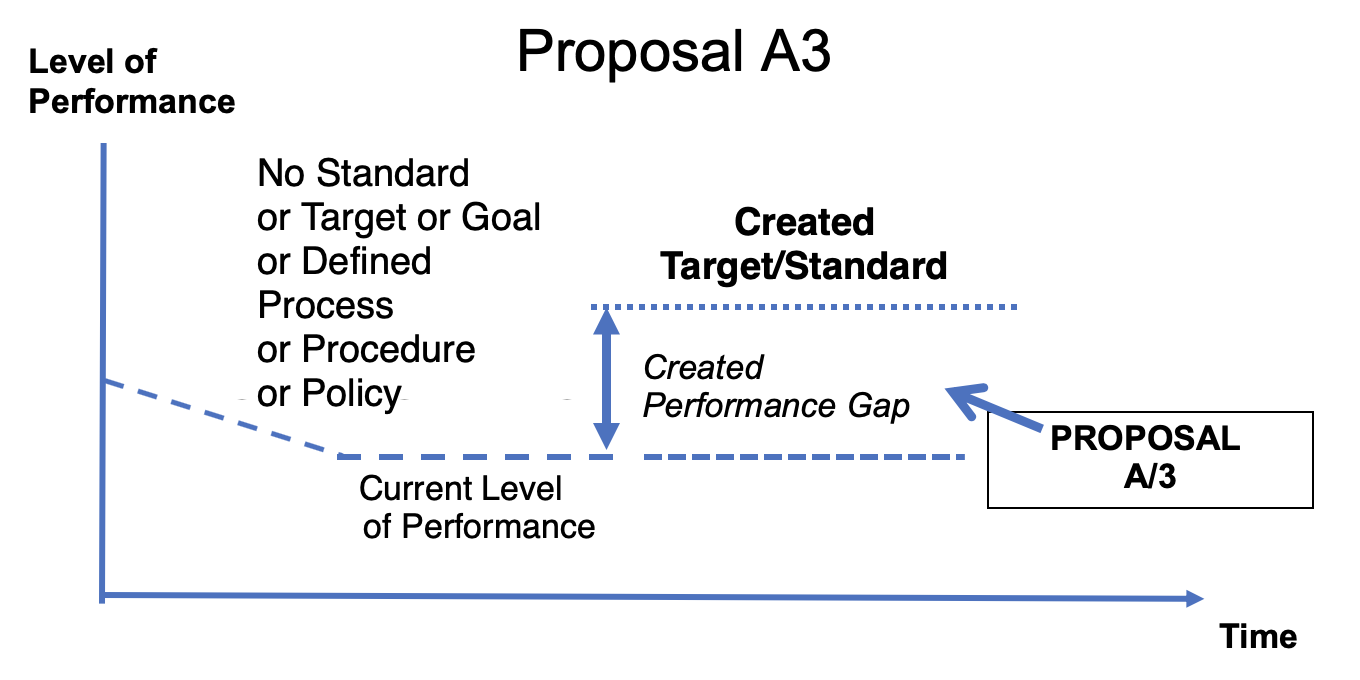

In situations where there is performance target or standard that is not being achieved, a Problem-Solving A3 is used to close the gap. In situations where a problem or need is recognized but there is not a performance target or standard, a Proposal A3 is used to set one.

An improvement in an unstable situation is like a drop in the ocean. It makes a splash but disappears very quickly. The fundamental principle of lean thinking, continuous improvement, and performance improvement that I have learned over the years is to stabilize as best you can first, standardize as much as possible, and then work on improving.

I recently saw an example of the confusion caused by unclear standards when I was coaching an engineering manager. He was the lead on a big project developing a new product for a client. He was frustrated with his engineers over their handling of engineering changes. After the product’s design was set in the original plan, the engineers learned things in developing it that made changes necessary. The manager’s problem was that the project engineers were frequently late submitting those changes to the client. And late changes meant penalties for his company.

The contract specified timing in the schedule by which engineering changes had to be submitted to the client. When changes weren’t approved on time, the original cost was applied, and the production company had to absorb the difference, which was generally higher. The engineering manager had reminded his engineers of this frequently and couldn’t understand why changes were often late. I suggested that we walk the process and talk to the engineers to find out what was going on.

We started at the end of the process, where engineers submitted the changes to a team that coordinated the master schedule and sent them to the client company. We learned from the person responsible for forwarding the changes that over 50% were late, which created extra work for her. I asked about the work process, and she said the engineers have many different responsibilities in the project, and they all know this is one of the things they’re supposed to do.

I suggested we talk to the engineers. We discovered that most of the engineers given the task of doing engineering changes were young, relatively inexperienced, and new to the company. They had not been trained or given guidelines on how to do the engineering changes. Most importantly, they needed information about the costs of the changes that they didn’t have the experience to calculate. And they weren’t told where they could get that information from the estimating department. Many of them said they were stuck because they didn’t want to get the estimates wrong. That’s why they were often slow in submitting the change requests.

In lean, we talk about the importance of standards and how they’re needed to clarify problems and manage performance. And we usually think of standards as targets, goals, and KPIs. But processes, procedures, and defined workflow are standards also; they are work standards. Toyota’s Standardized Work is a tightly defined example. If you set targets and don’t give people a well-defined path they can follow to achieve those results, you aren’t making them capable of the performance you want. You don’t have a target or a standard. You are just hoping they will get the results by their effort.

The engineering manager realized he was responsible for developing the processes he wanted his people to follow and training them to be sure they knew how to use them.

Achieving Agreement on a Standard

Fundamentally, a standard is a statement that says we agree on how things should be, or how we need them to be, in a performance situation. It specifies what is expected in a particular work situation. But a standard is not effective as an expectation that will guide behavior unless it is agreed to, documented, and communicated. Whenever possible, agreement on a standard or target needs to be reached with those who are expected to meet it.

I saw an example of this in a Human Resources department where I was consulting. I was asked to coach a recently hired HR specialist who was struggling with his first major project. He was to conduct training for supervisors on a revised policy they had to implement, and attendance so far was very low.

A standard is not effective as an expectation that will guide behavior unless it is agreed to, documented, and communicated.

Though relatively new to the company, he was responsible for updating an important employee benefits policy and educating managers and supervisors on how to perform their role in executing the policy. This young specialist was bright and had done sound research into the policy changes required by recent legislation. He had also created an effective program to inform leaders of the changes and show them how to help employees that qualify for the benefits. He had even done his first A3 and laid out a plan for implementing the training. He walked me through the left-side of the A3, and I understood what he was trying to accomplish.

When he described the right side of his plan, I asked if he had agreement to the schedule he’d laid out on there. His response was, yes, his manager and the vice president had approved it. I asked whether the management of the supervisors who needed to attend the training, particularly the managers in production, had agreed to the plan. And he said, yeah, I’m sure they do. That was a red flag for me. I looked at the training schedule and walked through it with him. I observed he had enough sessions to cover all the supervisors with one makeup session. And in the “Responsible” column, he had listed the other department’s managers as responsible along with himself.

I asked how he got their support with preparation for launching the new model that was going on at the same time. He replied he was sure they would do their part and support the training. It’s their responsibility, he said. My question was if he had their agreement on the training schedule. Well, not directly, he said. The executive committee approved the training.

I asked whether they had seen the schedule, and he said they hadn’t; it wasn’t ready when they reviewed the policy. So, I asked how he planned to get the managers’ support to improve participation, now that he’s doing the training and getting very few to attend.

The response was silence for two or three minutes. Then, he told me he’d sent them an email a month before the sessions started, telling them the training is mandatory and it was their responsibility to make sure their people attended. He added that he’d remind them that the law requires that they complete the training, and that the executives approved it.

I suggested that he needed to test the idea that they agreed to the schedule. I asked him to go to each department head or manager he listed as responsible, who had people who needed to attend, with an updated plan with additional sessions. I asked him to have them initial the responsibility column to indicate they will support it by scheduling their people to attend.

I didn’t hear from him again for about three weeks. I hoped he was out in the plant talking to people and that he was learning two things. First, you can’t just drop responsibility for something on people. You must make sure it works with their situation and priorities if you expect them to follow through on it. And second, you have to understand the broader context of what else is going in the company when you ask for agreement to a plan.

There is a term in Japanese, Nemawashi, that translates “to prepare the ground for planting.” Nemawashi is standard practice in Toyota for building a foundation of agreement to purpose, process, plan, and responsibility to get support for an improvement initiative, project, or problem-solving A3. The next week the HR specialist told me he had reached an agreement with the managers to a revised schedule that would start after the model change.

A3 is not just a tool for reporting problem-solving activity and seeking approval of countermeasures and executing a plan.

The A3 is not just a tool for reporting problem-solving activity and seeking approval of countermeasures and executing a plan. At Toyota, it is part of the process for leading change to address the operation and the business’s needs. It is a tool for documenting what is learned about how to improve performance and getting agreement and support for the necessary changes.

The A3 process is a technical problem-solving process based on the Plan-Do-Check-Adjust cycle. It is also a social process of engaging with and listening to others and incorporating their knowledge and thinking in developing a plan for change. The key to the entire process is that through it, the change leader gains agreement and support because it reflects the best options, methods, and timing available for everybody’s situation.

The A3 process works because Toyota trains its leaders in using it, and everyone knows it is how to address problems and make improvements for the good of the business. In other words, it is Toyota’s standard work for solving problems, initiating improvements, and leading change.

Managing to Learn with the A3 Process

Learn how to solve problems and develop problem solvers.