Q&A with Art Smalley, Author of Four Types of Problems

When faced with a problem many business leaders and teams mechanically reach for a familiar and standard problem-solving methodology — whether it’s brainstorming, fishbone diagraming, failure mode effects analysis, value-stream mapping, kaizen events, design of experiments, A3s, 5 whys, 6 sigma, or the 8Ds.

The problem is that the methodology is often mismatched with the problem, creating unnecessary struggle, frustration, delay, and ineffectiveness in solving the problem — if it is ever solved at all.

In this Q&A with LEI Communications Director Chet Marchwinski, veteran lean practitioner Art Smalley, author of the new book Four Types of Problems: from reactive troubleshooting to creative innovation, explains why settling on a favorite problem-solving technique or two is a mistake.

Most importantly, he explains how to slip the “hammer-and-nail” trap by understanding that most business problems fall into four main categories.

Art was one of the first Americans to work for Toyota Motor Corporation in Japan, learning the principles of its vaunted Toyota Production System (TPS) at the historic Kamigo engine plant, where TPS architect Taiicho Ohno was the founding plant manager. Art learned directly about problem solving from Tomoo Harada, who led the maintenance activities that created the stability that enabled Ohno’s innovations in flow production to succeed.

Q: What is the purpose of the book? What problem will it help people solve?

Art: Well the problem is that people try to apply one problem-solving approach to all types of problems. But not every problem requires a multi-step A3 approach to find the root cause. Sometimes you just have to contain a problem and get the production line back running.

The book is about different types of problem-solving routines and why they are necessary. Successful companies like Toyota employ more than one approach in reality. The problem the book addresses is finding a reasonable balance between using a one-size-fits-all approach and a hundred different techniques. I see companies falling into both traps, unfortunately.

Q: The term “lean” doesn’t appear in the title of your book. Was that a purposeful choice?

Art: Definitely. We started off with the working title “Lean Problem Solving,” and I don’t think anyone particularly liked it – especially me. I mean, what is “lean problem solving”? Are we inventing something new here? Not exactly. Problem-solving routines basically derive from the scientific method of plan, do, study, act. It also relies on many specific contributions by different people over the past 100 or so years.

There’s a tendency in the lean management movement to put “lean” in front of everything: lean product development, lean thinking, blah, blah, blah. It gets to be overkill after a while.

During development of the book, we thought about what lean problem solving refers to and said, “What if we talked about several different problem-solving methodologies and also referenced what Toyota does as an example?” After all, Toyota doesn’t problem solve just one way – and yet the average company often falls into this trap.

Q: Who will benefit from reading the book?

Art: Anyone and everyone. I problem solve all day especially with what we call type one routines, which are quick reaction and troubleshooting. It starts at the morning breakfast table with the family and making small adjustments to our daily routine.

I practice it in jiujutsu class for example with how to escape from bad positions or submission attempts, etc. At clients, we search for root causes to recurring problems etc. or to attain new target states. I’ve used the four types in service, healthcare, sports, industry, and national laboratories. It should fit everywhere if you grasp the fundamental concepts.

Q: Can you briefly describe the 4 types of problem solving?“Not every problem requires a multi-step A3 approach to find the root cause. Sometimes you just have to contain a problem and get the production line back running.”

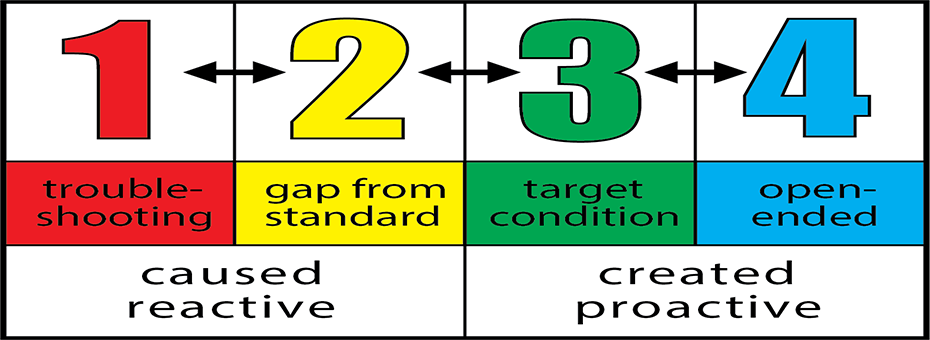

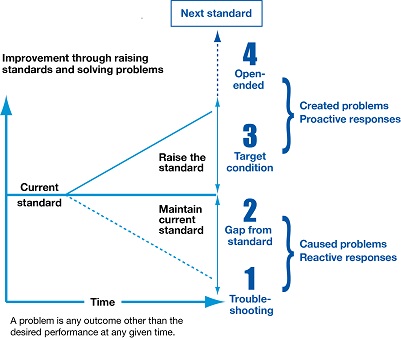

Art: First, you have type one or troubleshooting. In this type, an andon signal is triggered or any type of alarm or concern occurs and an employee responds. If necessary, a supervisor responds too. You try to fix the problem in a few minutes. There’s no A3 report written up or six-sigma team responding. You’re not creating a ton of documentation

So that’s why we have type two or gap-from-standard problem solving, which is a more disciplined and deliberate approach for problems that either recur or are more serious in nature. The key here is that we recognize there’s a gap from a standard in the problem definition, and it persists, or is severe and can’t be ignored. It also can’t be solved by troubleshooting; something deeper and more deliberative must occur. We usually must slow down and focus more to solve it at a more fundamental level. Type two uses a convergent thinking process and extremely critical thinking aimed at cause and effect relationships.

Type three is what in you or I would call kaizen. It’s also called target-state problem solving. So much confusion exists over the Japanese term I thought it was clearer to use the English phrase in order to make people think about it. In this third type, technically we are at a very stable and consistent level of operation so there is no problem, per se. For example, I’m shipping at 100% on-time delivery. Great, so no problem! However, I can still shorten the lead-time through the system to the customer. In sports, for example, the bar is always being raised each season due to competition. Last year’s playbook will not necessarily work as well again this next season. In Toyota, we called this a “created gap” and solving this new problem uses somewhat different thinking skills. It is more divergent and more creative in nature when compared to the previous types.

Then type four is just bigger, better, and even more future-state oriented than the others. It’s commonly called innovation, or we also use the term open ended in the book. It generally spans a longer time frame, involves a bigger change in the product, process, or system, or is entirely new. It starts with a clean slate and reconsiders the fundamental value proposition. Think of breakthroughs in history like penicillin or radar or the internet, etc. and you get the idea.

I like to say that you and your organization must learn to juggle four balls in problem-solving. Mastering just one kind can make you slightly better, but if you can tackle all four effectively as an organization while developing people then you will far outpace the competition.

Q: Why is it important to define a problem type before trying to solve it?

It goes back almost a century to the observation by American philosopher, psychologist, and educational reformer John Dewey that “a problem well-put is half-solved.” Different versions have been restated by various parties over the years.

In general, though individuals and teams simply can’t get traction without a clearly framed problem. Efforts get confused and muddled down as people go in different directions. An important step in the basic process, especially for Type 2 problems, is to clearly define the problem before jumping into the next steps.

Q: Where do popular problem-solving methodologies like A3, 5 whys, 6 sigma fit within the four types – does each methodology correspond to one type?

Most modern popular problem-solving methods like the ones mentioned are some form of Type 2 or gap from standard methodologies.

They can be used in other ways but the original intent for those was to frame problems in a step-by-step manner, get to the root cause (e.g. 5-why technique) and prevent the problem from recurring. Most popular routines involve logic and steps while true six sigma invokes more rigorous statistics.

The new book Four Types of Problems is now on sale in the LEI bookstore here.