The sound of the last bell of the day became slightly less piercing over the course of my four years teaching Biology. But only slightly so. Now, you might think that the last bell of the day meant the end of the workday. To the contrary, this tone mobilized a herd of students who, moments later, would come flooding into my classroom for the officially sanctioned ‘Extra Help’ period. This last 30 minutes of the day was a sprint to the finish, during which students would revise lab reports, correct tests, and conduct make-up lab experiments among other things (including attempting to cajole me into revealing any tricky questions they might find on the next quiz!). Overwhelmingly though, these students were in my classroom because they needed to review topics they had not fully understood during the lesson, and they often realized they needed this extra help only after they received what they viewed as an unsatisfactory grade.

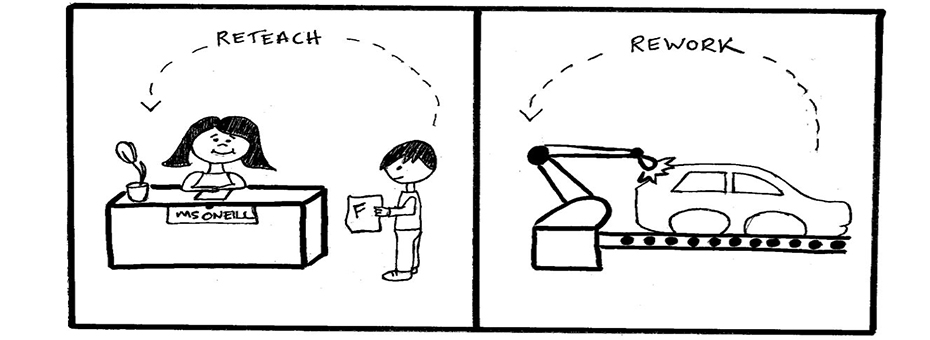

These students needed reteaching, or “rework,” and the number of students in my classroom was, to some extent, an indication of how effective a particular lesson had been. Unfortunately, because of the cadence of the course and the traditional way in which I had organized content and unit assessments, the students and I were often “reworking” concepts that had been presented weeks prior. Just as the sound of the last bell became less jarring over time, I developed new processes, through trial and error, in an attempt to address this problem that I now refer to as “rework.”

Over the course of the last year I began an MBA program where I was introduced to the ideas of lean thinking. As in most business schools, the ideas of lean were introduced to our class through the lens of manufacturing. Now, with a few B-school semesters under my belt, I am an intern at the Lean Enterprise Institute. I am taking a deep dive into the world of lean thinking and practice, in an environment where lean is being applied in contexts far outside the realm of manufacturing, and I can’t help but reflect on my time in the classroom. I find myself at once identifying parallels between good teaching practices and lean practice, and at the same time questioning the work of teaching through a lean lens.

As is customary in lean thinking, I’ll start with purpose, which, in the case of education, is to develop not only content knowledge, but also to develop in the student the skills and capabilities she will need in subsequent classes and years (the next steps in the process).

Once purpose has been defined, we must think about the ways in which the process speaks to purpose. Traditionally, classrooms and curriculum have a particular rhythm: content presentation, followed by activities designed to reinforce concepts and develop skills, followed by assessment. Either luckily or not so, I was given very little guidance in this respect, so I began to develop both the lessons and the cadence from scratch, iterating and adapting as I learned more about my role as teacher, and about my students as learners. This lack of direction and standards enabled (forced) me to embrace iteration and the “C and A” parts of the PDCA cycle.

In the earliest days, I would spend hours planning lessons, only to discover that the reality of both execution and the student outcomes and learnings from these lessons was often very different than what I had planned. I had planned new content without fully understanding the students’ current status and adjusting the next lesson plan accordingly. As a result, I spent a lot of time doing “rework,” reviewing concepts and reteaching one-on-one. While my main goal was to ensure that each student got the individualized attention he or she needed to succeed, accomplishing this through “rework” or additional hours of individual student meetings, diminished the time I had to plan, revise, and adjust subsequent lessons plans. Now, looking at it through my lean lens, I find myself wondering if this revision and one-on-one review is simply waste, or part of the value-creating process itself? Is there a way to make the assessment and the “rework” more deliberately a part of the value-creating process?

As I gained experience, I found my cadence for assessment and my tactics slowly changing, increasingly incorporating practices we typically associate with lean (though I couldn’t have named it that at the time); a phenomenon that speaks to the simplicity and the relevance of lean practice in all endeavors. I began assessing students’ understanding periodically throughout the lesson and requiring a quick check-in for understanding before they left the classroom for the day. We started grading smaller, simpler assessments together in the classroom. As the students graded their own work, it created time for them to reflect on what they had gotten wrong or misunderstood, and afforded them the opportunity to ask questions in the moment.

I am not the first person to think about this question of lean in the classroom, and there is certainly more thinking to be done. I have found, however, that many of the conversations have a slightly different focus. Many authors emphasize facetime with students as the value-creating work, while administrative work, assessment, grading, etc., is all considered incidental, or nonvalue creating. These authors often consider the teacher’s time in their efforts to drive change, focusing on improving the work for teachers, often by adjusting school schedules and rethinking the traditional organization of the school day. While this is important (providing more time for the C and A parts of the cycle to improve curriculum delivery is valuable), it does diminish the role of the student. The student is an active and influential part of the process; not simply the customer or the product, but an active participant. (Any teacher can tell you that the same lesson, delivered to two different classes, can feel very different depending on the students sitting in the room!)

These processes, rapid assessment, revision, and reflection, which help the student recognize their weaknesses, reflect on the method of preparation and learning style, and acknowledge their own gaps, are in fact skills we would like them to have moving forward! So this “rework” process, if done well, can serve both teacher and student. The teacher identifies common gaps across the class, making note so that the next days lesson can address misunderstanding, and so that the same lesson can be more effective on the next iteration, and the students learn to do personal PDCA while filling in the gaps that lead them to “rework” in the first place.

To the second point especially, I find myself considering this process in the context of lean leadership. One central goal of the leader practicing lean is to develop the capability of the people within their organization, to develop problem solvers. You can consider the work of a teacher in the same way. I realize now that while the more rapid assessment cycles I had begun to incorporate into my curriculum were a necessary step toward identifying whether students were ahead or behind daily and improving my own work, helping students to identify that for themselves is equally if not more important, and the process could be improved yet. I am itching to get back to the classroom to apply what I’m learning in lean in a more deliberate and intentional way… and to run some experiments!

I would like to understand how her lean training turned out in education. I worked in lean environments for 21 years and entered the education field in the last Democratic administration due to the last down turn in the economy.