My son’s sixth open-heart surgery, a heart transplant, took place just after his third birthday. The recovery was terrible, keeping him in the cardiac ICU for several weeks as his body struggled to adapt and heal. As with each previous hospital stay, either my wife or I was always present to comfort him and contribute to his care. Neither of us had a medical background, but three years spent navigating one crisis after another had helped us grow the ability to play a major role in care planning and execution.

This time we found ourselves struggling to contribute, as our deep knowledge of his congenital heart condition had been rendered irrelevant by his transition into the unfamiliar world of transplant medicine. I felt like I’d been set back three years, no longer of any value in his clinicians’ technical discussions, relegated to making feeble efforts to comfort a partially sedated toddler.

Like so many in our healthcare system, I felt helpless, like being carried down a rushing river in a raft with no oar – all I could do was brace for the next rock.

Despite this feeling, my training as a lean practitioner had ingrained the paradigm that any process can be improved, and that improvement works best when driven by an empowered process owner iterating toward their goal with a Plan-Do-Study-Adjust (PDSA) mindset. Longing for the old feeling of having a meaningful role in my son’s care, a process where I still saw myself as the process owner, I searched for a goal for our time in the CICU. I needed something tangible and important, yet achievable, despite my limited knowledge.

Finding an oar

In the months leading up to the transplant, my son’s feeding intolerance (i.e., vomiting) had become severe. To enable him to keep growing the medical team had placed a “J-tube,” a feeding tube that entered through his abdomen into his stomach, traveling far enough down his digestive tract that any formula delivered couldn’t be… returned. This J-tube did help him grow, but it also caused problems that affected his quality of life. Part of the thinking in the decision to transplant was the expectation (or hope) that a new heart would help resolve his feeding intolerance, allowing him to keep down food eaten normally.

So I proposed to my son’s cardiologist a goal of removing the J-tube by the time he was ready to leave the CICU. I think she chuckled. She certainly thought I was a little crazy. She agreed that this would be desirable, but this sort of project just wasn’t a priority in an ICU – especially with the challenges my son was facing. He was taking no food by mouth at that point, and the medical team had no practical way to work on this. When I assured her that my wife and I would do the work needed to get there, she agreed that we could propose steps to the team.

The first step, proposed in rounds the next day, was that my wife and I would try giving our son very small sips of his favorite nutritional shake. The plan was to give one teaspoon at a time, using an oral syringe, up to a total of two ounces for the day. The expectation was that he would be able to keep it down. The team agreed that this was safe to try.

It worked. So the next step, proposed the next day, was to give two teaspoons at a time, up to a total of three ounces for the day. The team agreed that this was safe to try, and it also worked. I had initially worried that these feeding trials might be a disaster, but it looked like we were onto something.

The power of experimentation

The project to remove my son’s J-tube required no medical interventions, no peer-reviewed protocols. The experts contributed a negligible amount of their time, adding little more than agreement that our steps were safe. The project simply required a parent’s knowledge of their child, plus the ability to iterate experimentally toward a goal.This experimentation continued for a few weeks, with my wife or I each day proposing to the team a small step that we would conduct. We learned that his gut was, as hoped, in dramatically better shape than before. As confidence grew, we moved beyond the sugary drink and began experimenting with more nutritious food – like fresh fruit, greens, and whole grains – pureed in a blender and tube-fed into his stomach. It started to seem like he could take anything we gave him, and eventually we completely stopped using his J-tube. A few days before he transferred out of the CICU, the team agreed that the J-tube should be removed.

This was a profoundly satisfying win, yet only a small part of this feeling was from having met the actual goal. Removal of the J-tube was a relatively small improvement in the big picture, and probably could have waited. The success of these experiments, though a huge relief, was not a huge surprise. Another small part of my satisfaction came from having proven to myself that I could still find ways to contribute, and I felt reassured that I would be able to grow into my new role managing the care of a kid with a transplant. A far greater amount of satisfaction came from something stumbled upon along the way.

When the experiments had started, my son was on severe fluid restrictions due to acute kidney injury. This left him perpetually thirsty – desperately thirsty. Being told “no” when he asked for a drink was crushing to him, and his spirit had sunk lower than I’d ever seen. While the team was worried about his survival for medical reasons, I was terrified by what looked like his eroding will to fight.

With the first experimental steps we learned that the tiny doses of his favorite drink seemed to lift his spirits. Although we had to deny his requests for more, we saw that he was comforted by knowing that he could have another syringe-full pretty soon. This discovery led us to focus our early experiments on increasing how much we could let him drink.

We were able to gradually give him more and more by mouth, balancing his fluid volume by pumping less and less formula into his J-tube, helping him ride-out the days until his kidney function recovered and the fluid restrictions were eased. Along the way we saw more and more of the funny, happy, resilient little boy that we had sent into surgery, and before long no one was concerned about whether he would make it home. Although it was impossible to know, I took deep satisfaction from the possibility that this modest campaign to remove a J-tube – motivated simply by a need to do something– may have unexpectedly discovered a key to his recovery.

Improvement is improvement

My son is now six years old and thriving in kindergarten, and managing his care while growing professionally as a lean practitioner over the past several years has left me convinced me that there are deep similarities in improvement successes or struggles in business and in an individual’s healthcare.

In every healthcare system and most of the lean implementations I’ve encountered over the past several years, I’ve seen essentially the same improvement model at work. It’s an expert-centered model where improvement itself is the purview of designated technical experts, and processes tend to be guided by business-as-usual thinking when the experts aren’t present.

Parallel roles in business and healthcare

|

|

Improving a process in a business |

Improving an individual’s health |

|

Technical expert |

Lean practitioner |

Physician, or other clinicians |

|

Process owner |

Responsible manager, team lead, etc. |

Patient, or a responsible loved one |

In both settings, this expert-centered improvement model seems to struggle at achieving transformational impact and sustaining results over time. Of course lean’s thought leaders have been recognizing failure modes in this model for some time, and there are a variety of proposals that in some way suggest greater responsibility and capability for process owners. Interestingly, I think a parallel awakening is happening in healthcare, where there are also a variety of initiatives around somehow leveraging patient engagement for better results.

Healthcare and lean seem to be exploring the same frontier: transforming to an improvement model centered on process owners. I’ve seen a number of lean implementations that attempt this in various ways, for example with broad employee training on tools or ubiquitous employee idea systems. Many organizations in healthcare are also taking steps to empower patients, particularly in the form of IT-based offerings.

Necessary but not sufficient

These stories seem to share a common theme of empowering process owners by giving them tools or information to support their improvement effort. This feels like a huge step forward, but I think something more is needed if these movements are to reach their desired tipping point of broad, transformational impact such that engaged process owners become the norm.

The success of these experiments was satisfying on several levels: they proved to myself that I could still find ways to contribute, and I felt reassured that I would be able to grow into my new role managing the care of a kid with a transplant.In my work as a lean practitioner, I’ve repeatedly seen that the vast majority of us are just plain unlikely to independently take awareness of a new concept or access to a tool and convert it into sustained, meaningful change (I include my own failed attempts here). That’s just not how people work: no matter how great the book, video, class, or suggestion, when we get back into the environment of our daily routines our existing habits tend to kick in and override our fleeting intention to do something different.

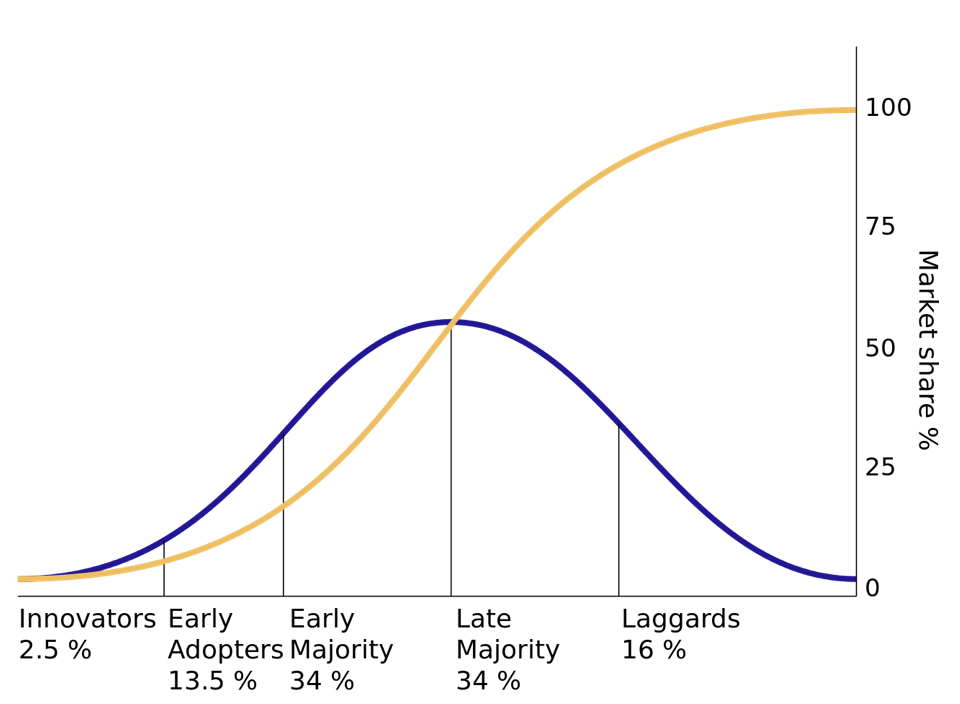

Reflecting on when I’ve taught people tools or concepts, it’s been a very small handful of outliers – the innovators and some early adopters, if you will (figure below) – who were truly helped by the exposure alone. Adding real value for people further into the population curve seems to require something more. That is, how to truly empower any given process owner to become an effective driver of improvement in their work seems to me the big question in both lean and healthcare.

Cars don’t think

A few months before my son’s transplant I suggested to my favorite cardiologist the possibility that emerging concepts in lean may be useful in my son’s care – or that of other patients. His response was crushing, as he dropped on me what I assume to be the refrain dreaded by every lean practitioner in healthcare: “people are not cars.”

Although this disconnect was frustrating in the moment, I have come to suspect that it actually hides some useful insights – including “how” to better empower process owners in general. Presumably, the refrain points out that people are varied and sentient. No two of us are alike, but each of us has rights, and the ability to think and act autonomously. Thus truly empowered process owners would need to think and act in a manner that produces improvement without a crippling dependence on experts.

The project to remove my son’s J-tube illustrates what this can look like. It required no medical interventions (i.e., no improvement tools). It involved no peer-reviewed protocols (i.e., no technical expertise). The experts contributed a negligible amount of their time, adding little more than agreement that our steps were safe. The project simply required a parent’s knowledge of their child, plus the ability to iterate experimentally toward a goal. Although the project had a modest goal, relying on the experts to tend to the bigger picture, it ultimately produced much greater value. These “pleasant surprises” seem to be a wonderfully common side-effect of good experimentation.

This ability to iterate – to think and act with a PDSA mindset – doesn’t seem to be something we’re born with. For me it was grown intentionally by my lean training, driven by an exceptional manager. This training involved repetitive practice and corrective coaching at a level of time, effort, and vulnerability that would seem absurd in most notions of workplace training. Yet the outcome – a truly empowered process owner – was well worth the investment.

No, people are not cars. They have the potential to contribute to better outcomes, lower costs, and fulfilling experiences in a way that cars cannot. Realizing this potential may boil down to finding ways to grow their ability to think and act with a PDSA mindset.