In 23 years at Toyota, I had many assignments and different bosses, I managed many people, but a constant part of the culture was what I’ve come to call “personal PDCA” – a kind of mentored self-development cycle. When it comes to personal PDCA, my first problem solving experience during my first ever assignment in Japan stands out for me.

On my first day at the office (in 1988), I was assigned both a mentor and a problem to solve. The organization I worked in was responsible for new model planning for global overseas markets – design input, grades, and specifications for Camrys, Corollas, and many other models headed to the U.S., Europe, other areas in Asia, the whole world. And within that Department, my group was responsible for Competitive Analysis. When planning a new Camry for example, we studied what Honda was doing with its new Accord along with all other competitors in that market.

Remember this was 1988 – the days before the internet or even personal computers. We relied a lot on magazine subscriptions for that analysis. During my first week, my manager called me over to his desk and said, “We are spending too much on these magazines and we’re not getting enough out of the analysis. Why don’t you put together an A3 on that?”

It sounded like a good idea to me, though I had no idea what an A3 was. I asked a couple people, learned it was a paper size, and started looking at what magazines we had. I talked to a few people about them, heard a couple of differing opinions, and a couple of weeks later set up a meeting to share my thoughts with my manager.

“I see two big problems: We are not getting the right magazines, so we should get more. And our people don’t seem to be doing effective analysis. We should consider hiring an analyst.”

He stared at my nearly blank A3 for a good 10 seconds and let out a long breath. “Have you confirmed how the magazines are really used? What is the problem you are trying to solve? It’s best to start over.” He turned over the A3.

Needless to say, my reaction was not good. “I thought you told me the problem,” I said. “Why didn’t you tell me what you wanted in the first place?” He just stared at me.

“Please find out more facts.”

So over the next several months, I rewrote that A3 about 10 times. By hand, in pencil. Toyota did not yet have a lot of computers, but they had plenty of erasers! I grasped the facts about how magazines were actually used by my co-workers and identified more specific problems. Each team member was using the magazines for his or her own reference and not sharing information. There were no guidelines on what competitive points to analyze. I created and implemented countermeasures for all of these items. As I wrote and rewrote, my manager provided guidance that pointed me in the right direction (which was usually in the pursuit of more facts).

After this experience of my first A3, I went back to my manager and told him, “I feel like I’ve added no value to this process. You’ve held my hand the whole time.”

“You’re right!” he said, and he wasn’t upset.

Many things flashed through my mind at that point. What strange company had I come to work for?! How could I continue to not add value on an even greater scale? This was definitely not the Toyota model of efficiency and effectiveness I’d heard about.

My manager continued, “Your first three years you will add little value. This is our investment in you. We will get our return.”

Some of my reflections at the time were: a manager should be clear on what he wants and communicate that. Toyota is an inefficient company that spends a lot of time solving one problem. My job is to find quick solutions to perceived problems in the workplace. My manager’s role is to give direction and let me do the job. Interestingly, looking back now, and most importantly – I see that my reflections then were all external. They were about how my manager should work, how the company should work, what was wrong with the situation I was put in.

They weren’t about:

- How I can improve the process next time

- How I can develop my capability to do better by reflecting on what I learned

Eventually, I became a manager in Toyota and by then, I was in the position of mentoring others. These experiences changed my perspective and helped me to develop my own thinking around personal PDCA – how to do it better myself and how to coach it.

In his book Workplace Management, Taiichi Ohno, a key architect in the development of the Toyota Production System, writes, “When you give an order or instruction to a subordinate, you have to think as if you were given that order or instruction yourself.” There’s more than meets the eye that quote. What he’s really saying is that a manager first needs to ask:

- How would he or she feel if given this assignment?

- How do we go about accomplishing this assignment?

- What is the work of this assignment?

- What capabilities are needed?

- Does the Team Member have those capabilities?

- How do I bridge that gap?

Recently I was at a large healthcare organization that has done a lot of good work to build a lean culture, particularly around their management system, using strategy deployment. But they were struggling with the basic building blocks of a lean transformation: daily problem solving and continuous improvement. As a consequence, they wondered if the improvements they were making would really stick. This is a real concern of many organizations and rightly so. Personal PDCA is the best way I know to close that gap.

A fundamental part of true lean culture is that everyone every day will improve their job. But that means the job will change every day, and therefore the team member’s capabilities will also need to be continuously developed. A manager must take responsibility to continuously develop his or her people, and both team member and manager must take responsibility for personal PDCA.

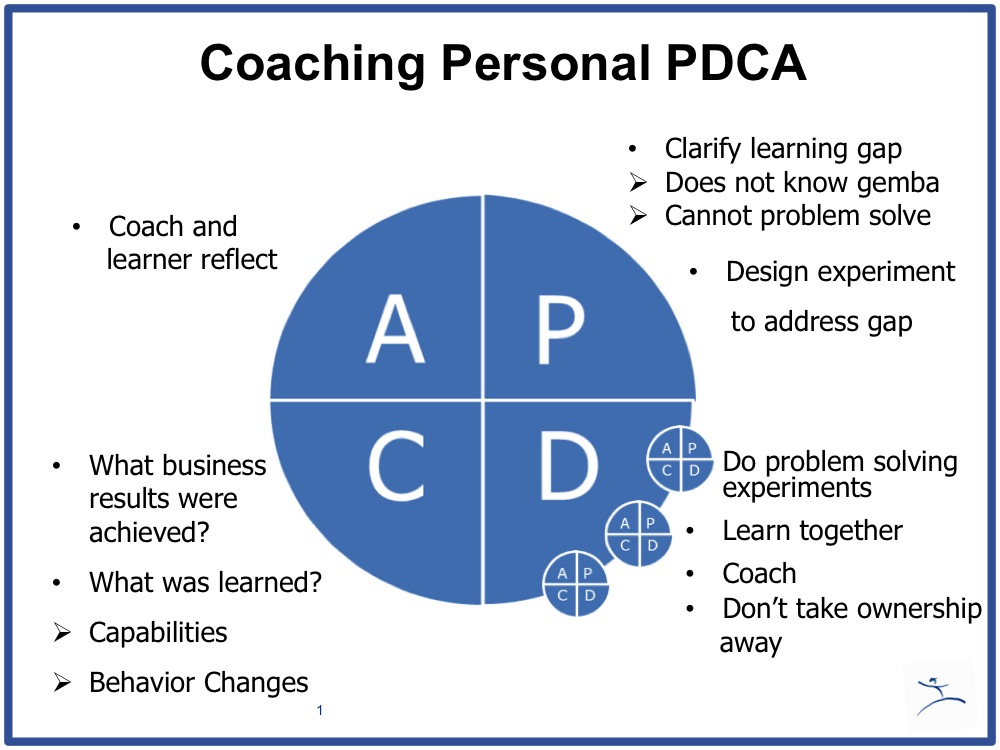

Here’s a visual I use and share with others to develop personal PDCA. Feel free to use it and let us know what you think!