An interview with Tim Benshoof, vice president – Finance and Strategy, Wonderful Pistachios and Almonds, offers updates on how the company continues to extend lean thinking and practice to more Finance and Accounting processes.

Mike: We featured Wonderful Pistachios and Almonds (WP&A) in our March 2020 newsletter with a description of the work you did to reduce waste and level-load the work in Accounts Payable, which in turn reduced staff overburden and improved the timeliness of payments. I know your lean practices are much more widespread in Finance and Accounting, so I would like to highlight those for our readers. Let’s start with the improvements you’ve made in the order-to-cash cycle. Please tell us about those and how they have benefitted your customers, your staff, and the company overall?

Tim: Order-to-cash was a priority for us because our processes didn’t support payments being consistently applied in a timely fashion, which could lead to customer frustration if customer accounts weren’t clear in terms of status — invoices and amounts outstanding. This issue had been a source of aggravation for many years for staff and the organization. And growth compounded the problem; WP&A has tripled in size over the past two decades.

Since our processes weren’t as effective as they needed to be, staff “made things work” — ensuring payments were applied correctly and timely as much as possible — through individual heroics. This situation seems to be typical in pre-lean organizations: relying on individual heroics to compensate for process deficiencies. Then when we first introduced lean and PDCA (plan-do-check-act), problem-solving teams (accounting, sales, customer service) worked separately on improvements, which helped to some degree. Still, a siloed approach doesn’t optimize the process overall. In fact, we learned that sometimes siloed improvements can actually make the overall process worse.

Through our hoshin (strategic planning) process a few years ago, we decided to focus on administrative functions, in addition to operations. It’s easy to see and pursue opportunities for improvement in manufacturing, but administrative processes can also have a significant impact on customer value and company results. In Finance, we selected order-to-cash as our focus and involved teams from customer service, customer credit, accounting/revenue, and IT.

In our first improvement cycle, we developed and implemented best practices in applying cash that became standard work across the teams. We also established cross-functional team huddles. These practices are beneficial because they ensure the teams have a consistent opportunity to raise issues and questions and have them addressed in real time because the right people are there. For example, in the case of a problem with a customer payment, there’s always someone in the huddle who has more information, and the team can resolve it right then and there or come up with a plan to fix it within 15 minutes. Without the huddles, these issues often would result in a string of 20 back-and-forth e-mails involving five or more people.

It’s important to measure the process: the team looked at the percent of unapplied payments and the time it took to resolve issues.

It’s important to measure the process: the team looked at the percent of unapplied payments and the time it took to resolve issues. The results of this first improvement cycle included a material reduction of unapplied cash and unresolved customer accounts and measurable reductions of process waste, such as streamlining the bank report process. We also reduced customer set-up issues; if the customer master isn’t correct, there can be challenges downstream with invoicing and cash application. For accounts with pre-payments, the team created a simple signal system — a message every time there’s an invoice with pre-payment terms to an order that hasn’t been invoiced or shipped yet. The signal allows the revenue team to see the pre-payment and move the account out of a problem status.

We started a new improvement cycle last summer with a similar cross-functional group. They mapped the end-to-end process to create visibility to connections to the customer-order process and prioritized and began work on the next series of improvements.

Early in your application of lean practices in Accounting and Finance, you implemented a box score — why did you decide to do this, what did you learn, and how has it helped?

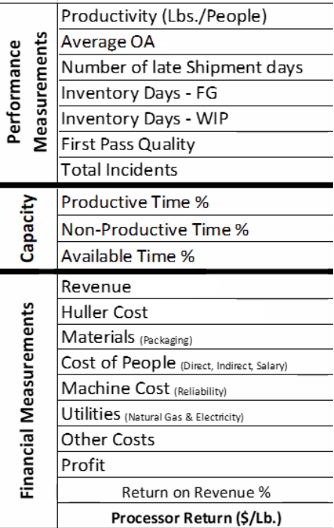

We piloted the box score starting in 2015 at one of our plants, a single, isolated value stream. Measuring and managing the value stream instead of department-by-department resulted in significant learnings and improvements in efficiency. The management team at the plant continues to use the box score weekly when Operations and Finance meet to discuss current performance. It provides them with weekly feedback to manage cost as well as improve production and inventory measures, such as maintaining low inventory aging. They have also used it to inform and monitor their work on level-loading. In the financial portion of the box score, plant management reports costs as period costs which simplified and improved the ability to set targets and manage labor and other line items.

We’re now working on producing value-stream profit-and-loss statements, which give us more reliable information to manage overall value-stream performance. The value-stream P&Ls will be monthly; our next steps are to share them with a broader audience to build an understanding of what they’re telling us and engage on how to use them to manage and improve performance.

You’ve also developed and implemented a rolling forecast to inform financial planning. In what ways has this improved financial planning and control?

The rolling forecast improved the efficiency and effectiveness of our financial planning processes. Previously we had separate financial plans done discretely by different people: a fiscal year budget, a calendar year budget, and a physical crop plan. Each was based on its own set of assumptions — some of which were different — and the process required a lot of discussions to align on interpretation and how to use them. Now we have one unified rolling forecast, and we can use snapshots in time for any purpose. For example, a fiscal year snapshot is used for audit, tax, and corporate-level planning. In addition, the forecast is organized by value stream and looks 18 months into the future.

We continue to work on identifying and refining forecast drivers and assumptions. We’re also exploring how to improve the use of the forecast structure — the operational drivers — and the forecast process to inform production planning. These next steps can create better visibility into opportunities to level-load.

… our improvements in financial planning have made jobs more rewarding and ensure we’re making the best use of staff’s skills and capabilities.

In addition to improving the effectiveness of the tools in supporting organizational planning and decision-making, our improvements in financial planning have made jobs more rewarding and ensure we’re making the best use of staff’s skills and capabilities. In the past, there was frustration with the sheer volume of reports the FP&A team produced, along with the constant reconciliation between them and the uncertainty that they were being used effectively, if at all. Now, the volume of reports is 30% of what it used to be, but the value they’re providing is significantly higher. The reports are designed with the end-user in mind, with clarity on what the information means and how it can inform the decision that needs to be made or the action that needs to be taken. Ultimately, for any lean accounting practices we’ve implemented, it comes down to ensuring the company has the reliable information and processes it needs to continue serving customers better.

Virtual Lean Learning Experience (VLX)

A continuing education service offering the latest in lean leadership and management.