Many organizations face the challenge of balancing the exploitation of their existing business model and value streams with exploring potentially new value streams. To do that, many have sought me out to bring a combination of design thinking, product design, and Lean Thinking. Their goal is to increase organizational capabilities around the design and delivery of products that solve customer problems with new or simply better existing products. This is sometimes called the fuzzy front-end, or the moment of customer pull. To do this requires that we return to two fundamental questions:

- Who is the customer?

- What is the problem? (or what is the job-to-be-done?, in Clayton Christensen’s words).

Many of these organizations have trouble answering these two questions with any degree of confidence. Most people have their own tacit understanding of who the customer is and what problem they have, but there isn’t a shared understanding across the product innovation or product development teams – everyone is literally on a different page. What some consider a rather straight-forward process of writing a well-formed problem statement is problematic for many people. When I’ve ask for a few paragraphs explaining the nature of the problem, who has the problem, and the context in which the problem arises, what I often receive back is a solution statement describing the future state or target condition – making it difficult to generate new potential solution concepts for new products.

As [inquirers] frame the problem of the situation, they determine the features to which they will attend, the order they will attempt to impose on the situation, the directions in which they will try to change it. In this process, they identify both the ends to be sought and the means to be employed.

– Donald Schön

To help with this, I recently developed the 4W method with the 4W Problem Canvas for teams and organizations to create a shared understanding of the problem domain, and to write a clearly defined problem statement. This is so they can begin the collaborative ideation process to envision new product and service solutions and use PDSA to test them, before iteration and scaling. (I find organizations and teams often jump immediately to solutioning, iteration, and scaling).

I’ll begin with a brief overview of 4W and A3 used in Lean Thinking and discuss how I believe they may actually be complementary, not competing, methods when teams are at the beginning of exploring a new horizon, product, or service to create new value streams. I’ll finish by unpacking, step-by-step, the 4Ws Method.

The 4Ws, A3, and Lean Thinking

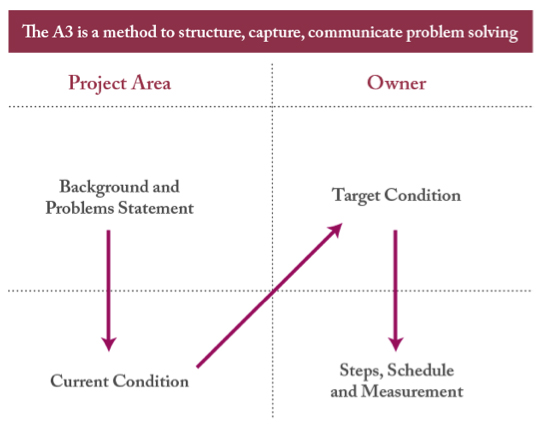

In the past few years, I’ve employed A3 in many different contexts to help teams understand the current condition, map dependencies and causal relations, posit a new future state or target condition, and define how success will be measured. This is incredibly powerful stuff.

One downside is that for people in knowledge organizations (like software design) with little experience with Lean Thinking, A3 requires some training. Often times, I just need teams to arrive at a shared understanding of the problem and surface their tacit assumptions. The other issue I’ve found with A3 is the format itself. An A3 sized sheet of paper is not necessarily conducive to true collaboration across a number of people within a team. Its big enough for one person to fill in, but even when a few people are working on an A3, the probability of premature convergence around the ideas of the one person with the pencil is high.

I originally thought of the 4W method as a light-weight, watered-down version of A3, but these days I think it can be used as a gateway drug to A3, or even better, to help drive a clear definition of the problem statement and current state to be written into the A3. If you think about the flow: from problem statement to current condition, to target condition, to countermeasures and how to measure success or failure – it begins with a clear, unambiguous, shared understanding of the current problem.

Unlike product innovation in knowledge work, within the context of deterministic systems, like manufacturing, it’s relatively easy to state the problem, current condition, and posit some target condition that is better than the current situation. This is the ordered domain of known knowns, or at least known unknowns – where there is at least a knowable causal relationship between things in the system. This is where I believe A3 excels, because this is the context in which this method arose.

In knowledge work, sometimes the target condition is some better future state that is both unknown and perhaps even unknowable. This is because many aspects of knowledge work like software design often exists in a more complex domain. So instead of generating one potential target condition, we create and test many possible options because we simply don’t know how the system will react to our intervention or probe. This is where combining A3 with other methods, like 4Ws and Design Studio, may help people leverage A3 as an overarching framework for problem discovery and problem solving, while applying other techniques within the A3 method for problem framing and concept creation.

I hope you find this method useful, and welcome any feedback you might have, especially if you try it in your organization.

Process for Facilitating the 4Ws

Materials for Success

- Post-its: multiple colors, multiple sizes

- Index cards: multiple colors, large size

- Sharpies: multiple colors

- Large-format easel pads with adhesive

You will also need:

- A quick 5-minute introductory presentation explaining 4Ws (PPT or PDF)

- Lean Personas (or Empathy Boards*)

- Research: any video, audio, interviews, contextual inquiry, or design ethnography to better understand the people for whom the designed solution should work, as well as any research which includes qualitative and quantitative data around the nature of the problem to be solved – the What that needs to be defined.

The 4W technique works best when a number of stakeholders who will be involved in designing, testing, and releasing a new product are participating. The key is having at least 6 people, to as many as 24, divided into teams no larger than 4.

Round One

Using the large format easel paper, draw with a sharpie 4 quadrants, and label each one with Who, What, Where, and Why, clockwise (link to PowerPoint again here). You will want to timebox this exercise. I have provided some recommendations at each stage of the process.

First, have individuals explore each quadrant by themselves silently. Each person writes at least 2 ideas that answer each of the 4Ws on 3×3 post-its. This should take about 10 minutes.

The 4Ws are:

- WHO: Who has this problem? Is it the customer? What do you know about the customer? Be as explicit as possible (sometimes people come up with more than one customer, and that’s okay to start).

- WHAT: What is the nature of the problem? Can it be explained simply? How do you know it’s a problem? What is the evidence to support that the problem exists?

- WHERE: Where does this problem arise? In which context does the customer experience the problem? Has it been observed? Can that context be described simply?

- WHY: Why do you believe this is a problem worth solving? Is it an acute problem? How acute?

After people finish and there are at least 2 post-its per quadrant, have the team spend 10 minutes presenting each post-it to other team members, and then place their post-its on the 4W Problem Canvas. After all team members do this, give teams 10 minutes to discuss all of the ideas. Ask them to notice, but not remove duplications, and to highlight and discuss contradictory insights. The point is not to drive consensus, but to have the conversation so that a shared understanding emerges – this is collaborative sense-making.

Sense-making is simply the collaborative activity that enables us to turn the ongoing complexity of the world into a “situation that is comprehended explicitly in words and that serves as a springboard into action” (Weick, Sutcliffe, & Obstfeld, 2005, p. 409). Thus sense-making involves—and indeed requires—an exploration of unknown problem landscapes, because sometimes trying to explain the problem is the only way to know how much you understand it.One downside is that for people in knowledge organizations (like software design) with little experience with Lean Thinking, A3 requires some training. Often times, I just need teams to arrive at a shared understanding of the problem and surface their tacit assumptions. The other issue I’ve found with A3 is the format itself. An A3 sized sheet of paper is not necessarily conducive to true collaboration across a number of people within a team. It’s big enough for one person to fill in, but even when a few people are working on an A3, the probability of premature convergence around the ideas of the one person with the pencil is high.

Round Two

Each team member takes a large format index card and spends 10 minutes writing a problem statement by themselves. The paragraph must explicitly reference the Who, What, Where, and Why as presented on the 4W Problem Canvas. The constraints are that problem statements can’t be more than 6 sentences, 150 words, and shouldn’t use more than 3 semi-colons (this is arbitrary, but sometimes people ask for this level of detail with constraints).

At the end of 10 minutes, each person reads their problem statements to the rest of their team. Each person gets 1 vote. The strongest one or two problem statements emerge. Teams then have another 10 minutes to re-write their problem statement based on the strongest 2 from the previous round, but again are constrained by keeping statements to two paragraphs max.

Round Three

In the final round, teams present their problem statements to other teams participating in the activity, or to external stakeholders who haven’t been part of the process. At this step, teams are checking their problem statements for clarity and coherence. You may use a formal critique method, but it can be just as effective to interrogate the problem statements to make sure they clearly articulate the Who, What, Where, and Why while also ensuring that no notion of a solution is embedded within them. If it is, it must be removed.

That’s the 4Ws. Simple.

The entire method, even with 24 people, should take under an hour. The benefit is that teams gain a shared understanding of the problem and leave with a clearly articulated problem statement. As a result, two things happen. First, when a team’s thinking process is transparent they can reach agreement faster. Many arguments and disagreements about the nature of the problem are actually disagreements about assumptions tacitly held. If we can’t make our assumptions visible, then they can’t be discussed. Second, making the thinking visible about the problem and customer enables coaching. You can’t coach outcomes. If someone just showed you that they’ve failed to define their problem, you don’t know why unless you can see their thought process.

Many organizations, even ones that are successfully practicing Lean Thinking, sometimes find it difficult to create a shared understanding of a problem and clearly articulate a problem statement. While A3 is a very powerful method, I believe that for some teams and organizations, there is value in trying the 4Ws method to collaboratively understand the nature of the problem to be solved, or the job-to-be-done. For organizations just becoming exposed to Lean Thinking, 4Ws may provide a light-weight, gentle slope introduction to PDSA. For more mature organizations, it may offer just one more tool in the toolkit.

I hope you give it a try in your team or organization and send some feedback so that we can iterate this method forward.

References & Resources

- Better Together: The Practice of successful creative collaboration

- Sensemaking: Framing and acting in the unknown

- Sensemaking and Framing: A Theoretical Reflection on Perspective in Design Synthesis

- Introduction to Design Studio Method

- Donald Schön Reflection-in-Action

- LEANUX: Problem Exploration Using the 4Ws

Problem Framing Skills

Improve your ability to break down problems into their specific, actionable parts.