“Lean isn’t a religion or a cost-cutting measure.” This has become my mantra.

I’ve learned that Lean is a comprehensive managerial system—and the best way to create value for customers, the company, and employees. Lean companies tend to better engage and empower their employees. Their facilities have many visual boards showing goals, trends, and assigned responsibilities. They usually share their plans and strategies. So you might ask yourself: “Why do those companies in the U.S. who are using lean thinking feel so afraid to openly discuss profitability and Lean?”

I recently got some very illuminating insight to this perplexing question by going to the gemba in Japan. I went on my first Japanese lean tour that included visits to a Toyota assembly plant and three Toyota supplier plants. In addition to seeing their legendary operations, I particularly wanted to discover if profit is part of the open dialogue within Toyota.

I understand why most U.S. companies avoid talking about profit and cost to their employees. It’s because, at an ever-increasing rate since the 1980s, we have implemented a horrible and for some a default tradition of “cutting costs,” which translates into laying off people just to make a profit target set by…. set by… well, set by someone. When we speak of “cost reduction”, we actually mean “driving down costs” without providing any context into the key related measures such as growth or customer demand.

In some organizations, we have gotten so far from the real value creation algorithms that we just speak in accounting terms based on standard cost like “variances”, “cost per unit”, and other cost lingo that is incomplete, short term, and basically not simple to understand or improve. We isolate these numbers from the holistic system with assumptions that eliminating variances will magically lead to healthier profits. All that the plant managers know how to do is just “make their numbers”. Often this means they will carry out irrational cost–reducing decisions, or they will manufacture more inventory to hide the manufacturing costs of the organization on the balance sheet. Making the numbers is equated with eliminating variance, regardless of the impact to production, employee suffering or inventory bloating. If you are not familiar with the issues with standard cost accounting, please read the book Real Numbers that I co-authored with Orry Fiume.

Given this current state stateside and my wildly disagreeing with it, I hoped that as part of my Japan trip I could learn more about how Toyota communicates its financial goals and targets since I was going to meet with a former top Toyota finance executive. Just like the people from operations who go to Toyota in Japan and return newly inspired by the promise of lean thinking (i.e. Toyota thinking), I was hoping to find some answers to my questions of how Toyota thinks about and presents financial information.

After all, it is not only in manufacturing that they are a superstar. As has been widely reported in the lean world, Toyota’s market capitalization has routinely far outstripped all other auto manufacturers. At this writing, Toyota’s market cap is $180 Billion, more than twice that of Volkswagen who is second in market cap ($80 Billion), despite Toyota and Volkswagen having nearly equal sales volume. And Toyota has a huge stash of cash. It is abidingly committed to the long-term employment of its employees and has strong, intimate connections to its suppliers. Toyota must be doing something right financially! But does it talk about finances? Does it talk about variance and standard costing? What could I learn?

After visiting one of the Toyota brand assembly plants and three tier-two suppliers, I can unequivocally say that Toyota very clearly talks about cost management. I never once heard any mention of variances or standards or any of the foolishness I hear routinely in U.S. traditionally managed plants. But, cost management and productivity improvement were on the lips of every executive that we met with at each of the four companies.

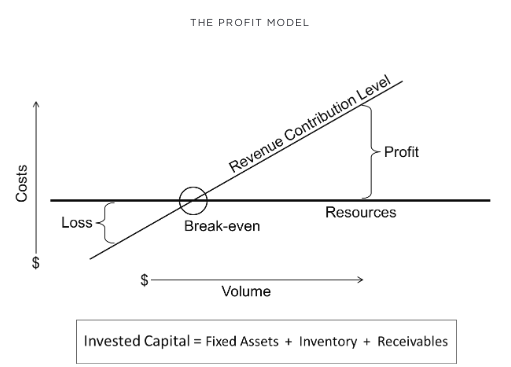

There was mention of the need to reduce manufacturing costs by a set percentage compared to the prior year’s actual (I heard 2-5%) at each location. The targets for both the assembly plant and for the suppliers was described as cost reduction as it relates to volume. Total cost based on shipped volume. Very high level, very specific and very long term. Every year. Always.

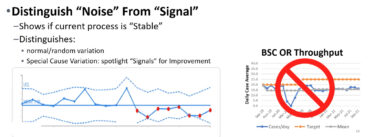

I did not get to see the exact components of the cost productivity measurement, but the measure was on the walls in many areas of the plant and offices. The chart was typically displayed as a total cost measure as a bar chart with several years and the downward cost trend/metric reducing each year. It showed this over several years, not just the current year. The context was clear: this is an ongoing expectation.

Not only was the goal of boosting cost productivity reinforced everywhere by these shared visual boards, but it was a given that achieving this would be done without any layoffs of permanent employees. And, safety and quality were the twin drivers of success to meet the cost reduction goals.

I was able to discover a bit about the components of this measure by asking questions and receiving general answers. Here is what I learned:

- The overall cost measure includes materials cost, not only labor and overhead. I found this interesting as the cost of materials was not determined at the plant level but through central purchasing areas.

- Not all employees are permanent. In fact, there is a labor shortage in Japan. So, there was a significantly high percentage of temporary workers, including many immigrant workers from various countries. It was obvious that the temporary workers were not relegated to less important work. In fact, one of the most impressive acts of change-overs, done in an almost ballet-like manner at a supplier plant, was performed by workers imported from Vietnam.

- The cost of capital additions is included in the cost measure. Whether it was the depreciation or the actual cost of capital purchased was not clear. I would guess it was capital purchased. By including capital cost, it rewards improved utilization of existing capital rather than just buying more equipment.

- It was not clear to me how changes in inventory were included in the cost, but I received an affirmative answer when asked if inventory levels were part of the cost. This was logical but a bit confusing to traditional accountant thinking. Inventory in U.S. accounting statements is considered to be an “asset” rather than a cost. I would have liked to learn more about how cost and asset intermingle in this metric. Is it a simple cost of capital or actual inventory reduction? By including inventory as part of the measure, hiding manufacturing costs in inventory is rewarded.

- Expenses of the plant included all costs including costs and benefits of improvement activities. Actual costs were used, not allocations. There was no effort to parse costs between different areas. The entire plant succeeded or failed together.

I wondered that given there are no layoffs at Toyota, how does it manage to reduce costs year upon year? I identified a few key elements.

- Use disciplined jidoka to aggressively reduce the costs of defects continuously. Actual cost reduction, particularly as it related to any types of defects: Defects were the highest level of unacceptability to my eye. By focusing on defect reduction, it lowered external cost and the cost of defect identification, rework, and problem solving.

- Reduce the costs of labor by boosting individual productivity and then reallocate those people to other activities. People capacity creation through waste reduction and then deploying that capacity to volume: Let me say this another way. When someone’s time to do a task is reduced by waste reduction, that person’s freed up time was utilized on a different value-adding task. Training was a normal part of preparing a worker to a new task. Work is rebalanced every 3 months at the assembly plant which enables the rapid utilization of capacity created from kaizen improvements. Workers did not stand by equipment waiting for it to complete. They moved from task to task in a takt rotation in every work sequence.

- Boost the capacity of existing equipment to fuel growth with existing—not newly purchased—equipment. Equipment capacity creation through machine maintenance: In four plants, we did not once see a piece of equipment stopped due to a maintenance issue. This is very unusual to many U.S. companies and indicates a very high capacity utilization is available for all resources at the plants we toured. Consider the amount of freed up equipment capacity from the norm that this implies. First, there is the capacity of the individual machine. But in Toyota’s pull system, the capacity of every other piece of equipment that is in the value stream must also be added. This capacity creation means that growth can be handled with existing equipment.

- Leverage ongoing kaizen gains relentlessly for ongoing cost reduction. Equipment capacity creation through waste elimination: Each piece of equipment ran independent of the worker, and the cycle was timed to ensure equipment was available at all times for the relevant task. Setup reduction was a key element in some of the suppliers. Use of standard work as well as standard equipment and standard tooling led to amazingly low setup times enabling the equipment to be changed over frequently to meet the mixed model demands in every plant.

- Every cost element is a target in both product and process development. Optimization and reduction of expendable costs: A very interesting example was karakuri devices that both removed human time as well as capital costs and utility costs. The thinking was always reduction, but not at the cost of quality and safety.

My visit reinforced my conviction that the lean profit model is the most comprehensive means to use when thinking about and presenting the financial benefits of lean thinking. (I expand on this theme in my book The Value Add Accountant.) Utilizing artificial numbers from standard cost accounting, focusing on meaningless short-term cost reductions, and managing profit by increasing inventory are all harmful and very much anti-lean thinking. Providing information that is difficult for all workers to understand does not respect people. Keeping profit (revenue and cost) information private or secret does not enable workers to fully understand the impact of an organization’s improvement efforts and the outcomes of their experiments.

Let’s learn the language of financial outcomes. Let’s learn how to unleash the financial promise of lean by identifying and utilizing freed up capacity. Let’s conserve energy and benefit from the environmental improvements that lean offers by reducing waste of all kinds.

I returned from Japan more convinced than ever, that lean thinking is the cornerstone of responsible management where the outcome is improved customer satisfaction, employee development and empowerment, and organization results.