It’s not unusual for North American hospitals to try lean for processes where patient flow most impacts costs or revenue. These efforts, if successful, often result in improved but isolated lean islands surrounded by healthcare status quo. Hôtel-Dieu Grace Hospital in Windsor, Ontario, also started in a common problem area (the emergency room), but with thoughtful rollout and eye-opening results has been able to expand improvements throughout the hospital, creating a “pull” from other departments that desire lean. As lean departments connect with other lean departments, a new way of thinking is satiating Hôtel-Dieu Grace and moving it toward a goal of improving the end-to-end patient experience.

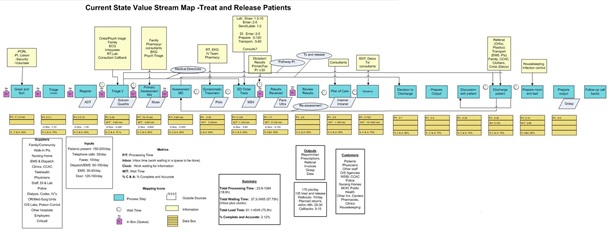

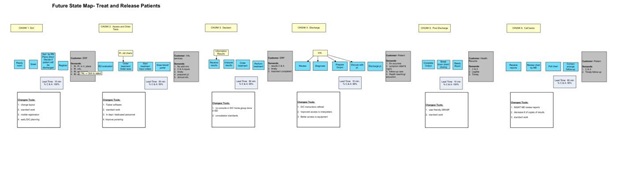

Since fall 2005, when the 278-bed hospital held a lean workshop for the emergency room (ER), five other departments have kicked off their own lean implementations — diagnostic imaging, clinical teaching unit, central sterilizing and reprocessing, mental health, and orthopedics. In each three-day workshop, cross-functional teams of participants constructed current- and future-state maps, highlighted gaps that represented the biggest problems or opportunities, and then collectively earmarked kaizen projects to tackle critical issues. From workshop to workshop, teams fought through traditional departmental boundaries, faced up to their problems, and found new ways to communicate and improve.

Lean has provided an approach that cuts across departments, personalities, hierarchies and the complexities of hospitals, says Neil McEvoy, CEO of Hôtel-Dieu Grace. “You have to get together very different groups to make change happen.” McEvoy and John Couglin, vice president, had reviewed various improvement methods through the years, but, finally, in lean tapped a way to address two fundamental needs for change within a hospital: One, an ability to see what was going on by describing the processes taking place in the hospital, and, two, a way to illustrate processes and illuminate problems for people who don’t bring an engineering or analytical orientation to their work.

“We stumbled upon this thing called value-stream mapping,” says McEvoy, “and that was really the doorway into lean.” McEvoy and Coughlin found a Lean Enterprise Institute workshop presented by the late Dr. John Long in Chicago, and subsequently invited Long to work with Hôtel-Dieu Grace.

“We found out it’s a lot more than value-stream mapping we could see this is something that is reasonably well thought out and has a good prospect of succeeding,” recalls McEvoy. “But it was much later when we had our emergency room workshop and saw what happened to the people in the workshop, that the lights really went on.

This was a lot more than diagrams. It was a lot more than reengineering. It was changing the hearts and minds of people.”

After a brief lean failure trying to overambitiously address the hospital’s portering process, from which valuable lessons were learned, McEvoy says a few key criteria were established for lean initiatives, beginning with the emergency room (ER):

- Champion and support: Chief of emergency medicine Dr. David Ng was energetic and looking for new ways of thinking, and ER staff desperately wanted change.

- Need: The ER was struggling with extraordinarily high wait times and an unhappy and occasionally dangerous environment.

- Control: Staff participating in workshops will be the ones to implement change and make the improvements.

- Benchmark: Hospitals across the river in Detroit were offering a 29-minute guarantee of service in their ERs and some in Michigan had begun implementing lean, providing targets and a benchmark of how Windsor could improve. The ER now serves as an internal benchmark for other Hotel-Dieu Grace departments.

“We were hoping that people would look at their work from a higher level and see how it fit in and how to change it,” says Coughlin, who has kicked off each lean workshop and offers an assurance that staff won’t improve themselves out of a job. “But it was much more than that. It helped with team-building, too. People in that workshop for the first time realized what other people on the team did. There was a newfound respect for every member of the team.”

Prior to the ER lean workshop “we were in perpetual crisis mode, lurching from one crisis to the next,” says Dr. Ng. The department, which sees about 60,000 patients annually, was in turmoil: long wait times, low morale, high employee turnover, patients leaving without being seen, patients and families angry to the point that increased security was necessary. Nicki Schmidt, a nurse in ER for 12 years, considered quitting. Lean, she says, offered some hope.

Dr. Ng attended a three-day kaizen at St. Mary’s hospital in Grand Rapids, Mich., and “was astounded. Ninety-five percent of the problems were an identical replica of what we had here. Never had I seen so much involvement from an entire staff and such concrete action plans and accountability set forth for the entire staff and department.” That, he adds, was a huge contrast to the top-down decisions within Hôtel-Dieu Grace with little feedback or staff input. “A lot of the things we did just failed. So for us having the framework to improve the department and change was probably the most critical thing of this whole lean process for us, even more so than the flow — it’s that the people who do the work finally have some control of the work.”

Schmidt was chosen by ER colleagues to facilitate improvements identified by value- stream mapping, and is now Hôtel-Dieu Grace’s Lea(r)n process improvement facilitator. The process change that provided the biggest impact was a redesign of ER layout and flow, creating a more efficient system to identify patients that would likely be discharged.

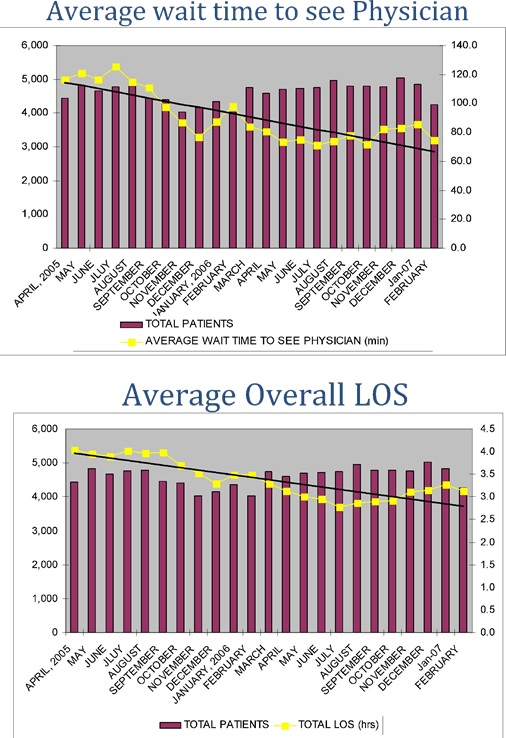

Efficiency at moving through discharged patients (about 85% of those that come to the ER) has cut wait times across all patients, even while patient volumes rose from 150 to 200 per day. The redesign also now empowers the treat-and-release nurses to pull patients into an open bed without waiting for the charge nurse to do it, which previously had caused waits and batching as the charge nurse has many other duties.

Lean participation among ER personnel has been high, peaking at 82% of staff that volunteered to do projects. Jeannie Macri, ER nurse and the current lean facilitator for ER, says keeping the momentum is difficult, but they’re constantly getting the word out with daily reminders and white boards, with the emphasis not on tools but the concepts and attitudes. “More nurses and more of the physicians are starting to be clear systems thinkers.”

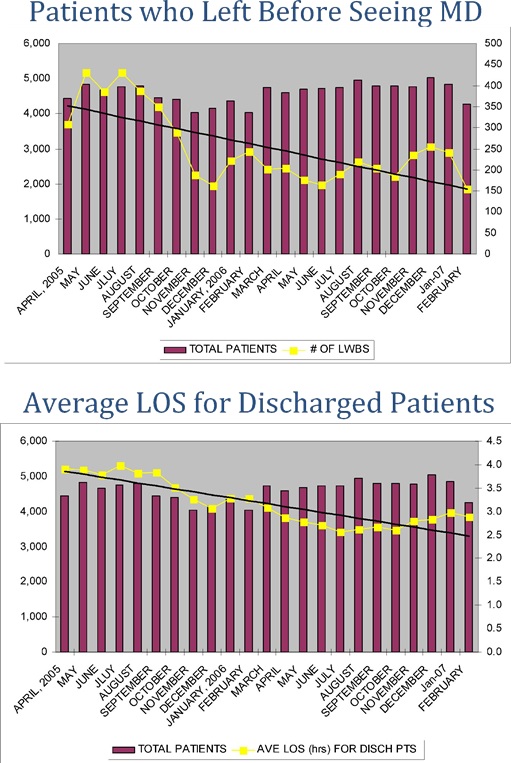

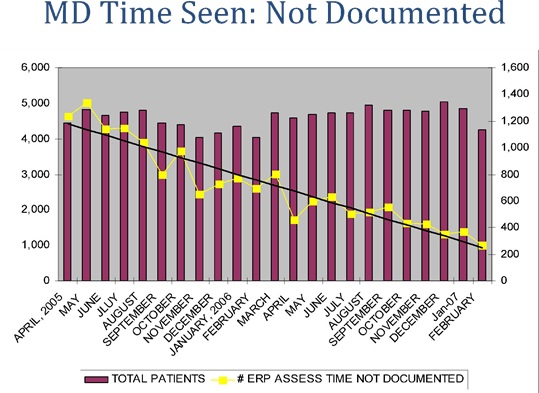

Although lean momentum has ebbed and flowed, the department is planning another push to address new issues that have emerged while they seek to maintain achievements amid rising patient volumes: (View related graphs)

- Patient satisfaction: Walkouts, whereby a patient quits waiting and leaves, dropped from 400 per month to about 150 per month. Complaints have also dropped dramatically.

- Wait time: Time spent within the ER dropped from an average of four hours to less than three hours, despite a 10% volume increase.

- Employee satisfaction: Labor turnover for the year after the workshop went from 50% down to 6%.

“We’re still struggling with a lot of sustaining,” says Dr. Ng, citing the difficulties of working on lean projects amid the excitement of an ER. But a lot of “things have been hardwired.”

“Nothing is ever done, and what we’ve realized since we started is that when you tidy up one issue more issues are apparent at that point. But I would never discount the amount of successes we’ve had,” says Macri. “The successes we’ve had have been huge when you sit back and compare them. And we are riding change better now than we ever did before.”

With the Canadian healthcare system, provincial governing bodies define the services hospitals offer and establish budgets based on service volumes — so despite a sudden rise in ER patients and overall increased occupancy, Hôtel-Dieu Grace can only address the issue through increased efficiency (no added revenues, no unbudgeted hiring). It can take as long as three years for budgets to catch up, says Eleanor Groh, director of emergency cardiac care and medicine. “The challenge now is to continue to see those additional volumes … with no additional resources coming into the department. There’s the ROI.”

The biggest return to Hôtel-Dieu Grace from the ER lean work may be the cultural and benchmark impact throughout the hospital on other departments, many of which participated in the effort. “We set ourselves a ground rule that the problem has to be solved with the group that was there,” says McEvoy, referencing the failed portering initiative. “That meant that when we dealt with the emergency room, a number of other departments that are part of the value stream for the emergency-room patient, such as laboratories and diagnostics imaging, were invited as participants in the process as observers and supporters rather than participants in changing their methods.

“We ended up with these people witnessing the transformation that happened within the department, and went away to their own people saying, ‘Look what happened over there.’ The word got out and the enthusiasm spread in other areas. We had pull coming from other areas, asking to be part of it,” McEvoy says. People were surprised by the complexity of their current-state processes and energized by the possibilities represented in future-state maps, he adds, but “I don’t think we realized how profound the interpersonal reaction would be. We didn’t realize how magnetic the whole thing was going to be.”

While the workshops, kaizens, and goals vary among subsequent departments, a common theme is that lean has provided a structured, non-political manner to see and improve processes, communicate with coworkers, deal with problems, and better serve patients:

Diagnostic Imaging

The diagnostic imaging department provides “the pictures” — X-rays, computerized tomography scans, etc. — that enable physicians to see and diagnose what is not normally visible. Similarly, use of lean in the department made problems visible: Rework of images. Patients backed up into hallways. Everyone frustrated by the inability to make improvements in a timely manner amid top-down management and dysfunctional working relationships.

“We knew that something wasn’t right, but we couldn’t fix it,” says Dr. Fred Netherton, chief of radiology. “Things were started but never completed.” That began to change with the lean workshop in which everyone came face to face and released pent-up frustrations. Netherton advises that “instead of excluding the people that are giving you the headaches, make sure they’re there. Ultimately they’re the ones that are going to turn around and give you the most advice.”

Mary Alice Beneteau, director of diagnostic imaging, says mapping enabled the varied roles in the department (clerks, technologists, radiologists, porters, etc.) to see their contributions as well as the contributions of others, and “everybody realized they add value.” Staff also saw how their cobbled-together system was failing. Mapping current vs. future states led diagnostic imaging to identify seven projects “where we could get the biggest bang for the buck and where big changes needed to happen immediately.”

Projects addressed the redesign of workflow and standardization of quality objectives. Previously 30 steps were needed from when an order was received in the department until the technologist (the one taking the pictures) acted on the order, a centralized approach in which everything moved through a room of clerks. Now it’s two steps, Beneteau says, with a clerk and technologist sharing workspace. This has reduced leadtimes as technologists and clerks jointly address questions about an order upon receipt (rather than passing it repeatedly back and forth) and enables technologist to focus on their work rather than making telephone calls and hunting down answers.

Leveling the workload of technologists also has reduced wait times and patient queues and, thus, improved quality in that technologists aren’t rushing to get caught up.

Leveling also ensures that enough technologists are staffed to handle larger patients. Better coordination with other areas within the department, such as portering, also has helped to reduce wait times (previously a patient needing two procedures might be brought to the department twice and wait twice).

Many of the quality issues in imaging were due to the lack of a standard for a quality image. “There are a million ways to do it wrong,” says Dr. Netherton, and “there were six perfect ways to do it” (There are six radiologists in the department).

“Radiologists got together and standardized their protocols. Now there is a standard set of expectations that technologists can measure their performance against,” says Beneteau. In the end, Dr. Netherton and the other radiologists realized their personal standards weren’t so different. “The number I [now] send back are very few, and quite often it’s not a technologist problem as much as mechanical or something else,” says Netherton.

Lean has provided a context to discuss problems and processes apart from emotions and is encouraging open-door communications, Beneteau says. And a prominently placed white board facilitates openness. The board tracks the lean projects underway, invites comments and questions related to goals, and opens everyone’s eyes to unseen problems and issues. Comments are dealt with at weekly meetings, and resolutions presented then and there or delegated to a future lean project.

“If you have an issue, go write it on the board and sign your name. If you can’t put your name to it, then let it go because it can’t be important to you,” says Beneteau. “It helps people understand we’re hearing them and listening to what they say, and giving it value every time something is said.”

Clinical Teaching Unit

In July 2006 Hôtel-Dieu Grace began its clinical teaching unit (CTU), an education program for residents and clerks affiliated with the University of Western Ontario in London and a precursor to a satellite medical school in Windsor. While medical staff and attending physicians conduct the teaching of residents (postgraduate trainees) and clerks (senior medical students), CTU management must ensure they’ve got patients in the 26-bed unit from which learning can take place (typically internal medicine patients that have not been diagnosed).

From a process perspective, an ER physician identifies a potential CTU patient, the physician calls in a resident to observe and discuss, and then a decision is made to place the patient into CTU. That’s how it should work. But, as expected, building a program from the ground up presents challenges, says Dr. Osmond Tarabain, subsection head of internal medicine.

“We know we had problems, and problems were palpable on all levels,” Dr. Tarabain says. “There were a lot of frustrations in the emergency department getting internal medicine patients out, getting internal medicine students to see patients, problems on the floor moving patients in and out from admission to discharge. There were problems with the educational components for the house staff — with all that chaos that was happening, the education experience was compromised.”

Six months after ramping up the program, staff held a lean workshop. Dr Tarabain says, “We were fortunate to have a [lean] guinea pig department in this hospital, and that was the emergency room. So we saw how it worked in the emergency department, and that was encouraging.”

CTU staff mapped current vs. ideal procedures, and used that to identify kaizen projects. “The old current was that we were just sort of flying by the seat of our pants,” says Raettie White, manager of CTU. “It was a new program, and we didn’t know what to expect or what we were going to do. We thought we’d just start working things out as they happened.”

Nearly all CTU patients come from ER, and so ER and associated handoffs became an area of focus. CTU partnered with ER to map and understand why patients were not making it to their unit. What they found was that residents and clerks took too much time getting to ER to see a patient, and when a CTU patient was identified, admitting often did not get notified in order to send the patient to CTU.

“We weren’t communicating with each other,” says White. “[Admitting] didn’t know [patients] were supposed to come to this unit, and they were getting admitted throughout the building. Then we were having to pull them in, which is a lot of rework by everybody.”

Out of the workshop a series of “negotiations” transpired, such as getting ER to notify admitting and getting residents and clerks to agree to being at ER within a set time. “The resident would respond within 20 minutes, the clerk would be down within an hour, and the process of admitting the patient and doing the assessment and the orders would be done within three hours (a period of time that includes a teaching component),” says Jody Quenneville, CTU nurse.

Getting patients to CTU has, ironically, made it easier to notify clerks and residents they’re needed in ER: Because CTU patients were dispersed throughout the far-flung hospital, residents had to traverse many departments looking for them, which then made it difficult to find a resident and get them to ER to properly admit CTU patients. “If they’re all over the building, the other units aren’t going to tell them you’ve got four patients waiting in [ER],” says White. And since the hospital is at high capacity, an empty CTU bed will get occupied by somebody (CTU or not), so it’s important to get CTU patients in those beds and eliminate shuffling of patients from department to department with residents and clerks in pursuit.

“The goal of the project was making it a teaching environment, and not having the patients on the floor did not provide a teaching environment,” says the hospital’s lean coordinator Schmidt. “Raettie was running around to different floors, and their rounds were three hours long. They are an hour and a half now, so they cut their rounds in half.” And based on post-kaizen monitoring, 72% of patients in ER had been seen by residents within the negotiated timeframe, says Quenneville.

Lean improvements in CTU are helping to better educate, monitor, and produce quality young doctors, says Dr. Tarabain, and it’s also building a positive image among the emerging doctors that can impact the hospital and region for years to come. “We’ve seen the feedback from the medical students for the first six months before lean and the six months after lean, and it’s black and white,” says Dr. Tarabain. “In the last six months it was extremely positive. There is not one negative feedback. They’re happy with organization, they’re happy with nursing staff, they’re happy with everything. Even the folks in the ‘mother ship’ in London were amazed by this transformation. I think we owe it to what lean has done for this program. … Having this positive experience in succeeding in setting up the CTU will attract more doctors into this community.”

Central Sterilizing and Reprocessing

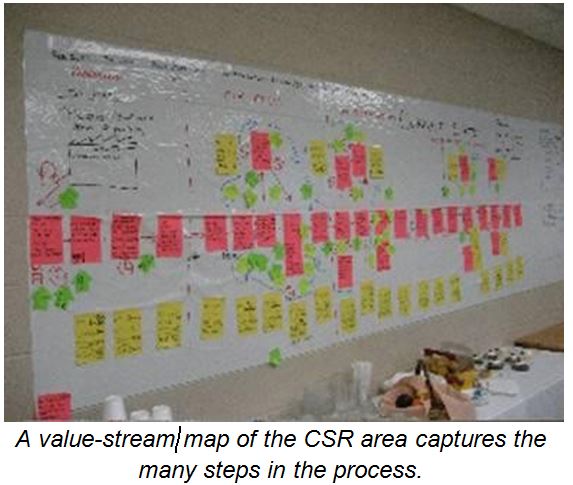

For any surgical procedure that occurs at Hôtel-Dieu Grace, there are a vast array of devices and materials that must be sterilized, carted, and waiting for surgeons. Buried within the bowels of the hospital sits central sterilizing and reprocessing (CSR), where used materials are cleaned and sterilized and storage racks house more than 5,000 pieces that can be needed on any given day for the more than 23,000 surgeries performed annually. CSR must pick the right devices and deliver them to the right surgery at the right time.

The CSR process cuts across a unique mix of professionals — surgeons, assistants, nurses, CSR staff. In the past this mix of viewpoints combined with poor communication led to assumptions, blame, reworked orders, and last-minute fixes, says Sheila Bennett, CSR supervisor. The lean workshop brought together the disparate parties, focusing their attention on three specific processes: booking and receipt of preference cards, picking and preparation of carts, and instrument recovery.

Booking consists of a surgeon scheduling a procedure by faxing the request to the booking office clerk. Once the operating-room cases are booked, the preference cards are printed and the case carts are assembled. Preference cards list surgery specifics such as procedure, time, place, doctor, etc. Lack of standardization was a major problem as surgeons and their staff used different names for identical procedures and/or devices. “CSR, RNs and the physicians all speak a different language,” says Schmidt.

CSR has begun to apply standardization by offering a list of options from which surgeons and staff must select. This process change is coinciding with installation of a new computer system that will eliminate manual preference cards and should make it easier to standardize information. “When they choose to book a case using web-access from their office, they’re only going to have a list of what they can choose,” says Virginia Walsh, perioperative and inpatient surgical director. “They can’t make one up. That’s how we’re going to steer them toward common names and standard procedures.”

Once preference cards get to CSR, staff pick items from a storage area that holds sterilized devices and items that get replenished (e.g., dressings, linens). Complicating the work, surgeons can request that materials appear at certain positions on the operating-room carts. To improve the speed and accuracy of picking, CSR spent more than a month revamping the storage area, creating a pathway to efficiently wheel and load carts: common materials are stored on a perimeter route, with a device route in the center the least-required components are set aside from the primary flow.

“We realized there are certain things that cross over every type of case, like a dressing,” says Bennett. “And those would be something we pull for every type of case, regardless of the surgery. Since that’s the case, why don’t we begin there.” Accelerating the picking, the new computerized preference cards are printed with items listed in the order of appearance on the path. The storage area also was improved by applying 5S, such

as reviewing the purchase of items and overstocks. Evaluation and treatment specialists were called in to approve the elimination or reduction of items.

Once loaded and organized, carts are then delivered to the operating rooms along with the preference card/pick list, where an RN will reconcile items. Previously, CSR would pick from one list and the RN would proof from another, leading to inevitable differences and rework.

Lastly, everything that is not disposable is returned to CSR for sterilization and storage, a 24-hour-per-day operation with an emphasis on equipment monitoring and maintenance. Additionally, CSR must work in the scheduled delivery of linens and disposable items. A kaizen project will look at more efficient ways to “break down” the carts and get materials back through to CSR storage.

“There were a lot of tensions in the beginning, and a lot of blame during the workshop and even the first month or two,” says Bennett. Gradually the negative emotions and fingerpointing began to dissolve, replaced by an understanding by all parties of the roles they play. “The other positive thing I’ve seen come out of this has been the communication and the willingness to change something that has been there forever and ever.”

Mental Health

The mental health department entered its lean workshop looking to discharge its patients safely and in less time. It’s a complex challenge, given that it encompasses the mental-health-patient journey from admitting to discharge and, as the lean team found out, one fraught with problems, including few decision protocols to access services, lack of formal training for everyone who comes in contact with mental health patients, lack of standard procedures for discharge decisions, patients seen by multiple psychiatrists (with multiple forms and redundant assessments), and lack of communication.

“It was a very disjointed department physically and the way we worked operationally,” says Robert Moroz, social worker and lean facilitator in the department. Compounding the difficulties was that the Hôtel-Dieu Grace department was merging in an offsite mental health department.

“Length of stays were horrifically long,” says Sonya Grbevski, director of mental health, “and we weren’t doing the right job at the right time.” Grbevski was familiar with lean because her husband works in the auto industry, and extremely frustrated by the lack of process thinking that existed in the mental health department. But what made her most frustrated, she says, was “watching the rest of our staff, watching our patients. Every day was so hard.”

Delays in assessing and treating patients in mental health limited the department’s ability to admit new patients, which meant that those in need of care were left waiting elsewhere, often in emergency room beds. Almost 100% of mental patients come to the department via ER, an area not conducive to mental-health care. “That type of environment for a psychiatric patient is the worst you can possibly have,” says Carrie Mangold, manager. “Every hour you add to a patient’s stay in the emergency room they just escalate. So by the time you get them upstairs, the patient is over the moon and the staff is starting not even from square one — it’s a huge impact. There length of stay is increased.”

“And there treatment is now delayed,” adds Grbevski. “Their treatment should begin at the time of entry.” Since the mental-health lean workshop, wait times for mental health patients in ER had fallen from nine hours to two hours [average].

“What they found in their workshop was that a lot of their processes were not standardized,” says Schmidt. This was particularly true with how handoffs between areas occurred — such as ER to mental health or mental health to discharge.

Discharge procedures have been redesigned to allow patients to be referred to a partial/day hospital and start services there the following day. This process previously would have taken weeks from the point of discharge to partial-hospital support for the patient. Safely moving patients out sooner, means lower leadtimes to get new patients in, and, most important, this change means that patients now continue treatment without interruption. Previously, there could have been a six- to eight-week interruption from the inpatient unit to the outpatient clinic, and that would have required them eventually being admitted.

Other improvements underway include basic mental-health education for all staff (e.g., nurses, occupational therapists, physical therapists), working to better measure care and measure improvement in patients (pulling standards from other hospitals and government), and working at getting more doctors more actively involved in lean (rather than passive support). The end goal of improvement, says Grbevski, is “quality of life for our patients and quality of life for ourselves. We believe they’re correlated.”

Orthopedics

The lean work underway in the orthopedics department is unique for Hotel-Dieu Grace or any hospital. It encompasses a patient value stream from prior to admission through orthopedic surgery, discharge, and recuperation, with a goal of reducing the in-hospital length of stay.

“Patients on our floor are primarily elective they know their surgery is coming up, and they know they’re going to need somewhere to stay,” says Joe Karb, manager of orthopedics. “Nobody was planning for that. They’d come to the hospital, and on day three we’d say, ‘You need to go somewhere other than home.’ That’s what prompted me to want to do a lean project.”

Karb had seen the ER successes with lean and wanted it to work in orthopedics. “My background was emergency nursing. It was uplifting to see the changes they were able to make and the impact on that department.”

Orthopedic patients were staying an average of eight days, but the clinical guidelines were a four-day post-operative stay. Karb says a high percentage of patients stayed five to 17 days some stayed much longer, primarily due to complex health conditions.

The lean orthopedic workshop took place in October 2006, and the team (nursing, social workers, orthopedic surgeons, occupational therapists, physical therapists, administrators, etc.) evaluated segregated patient types and assessed how planning could impact their stays. They identified patients as those having normal procedures and in good health with home assistance in place normal procedures but socially complex patients who would be difficult to discharge based on present living situations (about 70% of the group that was staying five to 17 days) and medically and socially complex patients.

“Out of that we bred the idea of the Total Joint Clinic,” says Karb. Many workshop participants had envisioned a clinic in some form, and together they designed a presurgical clinic where patients have a physiotherapist assess them, a pharmacist review their medications, a nurse to do a history and physical examination, and, most important, a social worker to plan for their discharge.

Ideally the clinic would be on the Hôtel-Dieu Grace campus, but the hospital had no space available. They negotiated with Royal Village, a retirement home that offers convalescence, for clinic space. Royal Village was interested because it usually takes about 10 to15 days to recover from knee surgeries, making Royal Village a convenient option for patients.

Finding and establishing physical space was a challenge, but process changes were still at the heart of the lean effort. “We also found there was a physician component to the length of stay as well,” says Karb. “Some physicians would say to the patient, ‘You can stay a week, you can stay 10 days,’ while others were strict on the four days. That also was addressed on the workshop. The physicians that attended made it very clear it was going to be four days and nothing more. Now that issue has been resolved.”

The workshop also revealed that orthopedic nurses followed the patient’s pathway only about2% of the time. Pathways are guidelines describing what a patient should be doing for recovery in order to exit in four days. They are designed to reveal patient-recovery variances, ideally leading to interventions in order to overcome any variances that arise. “Our staff weren’t using it because it was not put in the patient’s chart, it was not a legal document,” says Karb. “They were not stored in health records. Staff felt, ‘If it’s not part of the chart, I don’t need to worry about it.’”

Staff changed the format of the pathway to make it part of the legal patient documentation, and simplified it (less redundant work). Compliance improved dramatically, initially hitting 100%. Another improvement to address patient length of stay has been to better utilize white boards in patient rooms and in nursing stations to communicate recovery information.

Orthopedic patient changes, such as the social worker role and prepping the socially complex group, were in place soon after the workshop, and the Total Joint Clinic went live in June. “They’ve done a really good job,” says Schmidt. “They’ve actually increased their number of patients, and almost doubled the number of patients that meet their discharge date.”

Other lean changes throughout orthopedics are addressing waste reduction (materials and time). Staff are reorganizing a supply room that was built in the 1940s and hasn’t changed since (making material visible, reducing inventories, preventing hundreds of dollars of wasted stock). They’re also assessing how shifts are staffed and reports made from shift to shift. Verbal reporting now consumes an average of 42 minutes and a high of three hours. “Over the three shifts, we’re losing two hours of productivity per nurse,” says Karb. “We understand things have to change.”

Lean Future

Lean will eventually take on two big challenges and areas of change at Hôtel-Dieu Grace, first the operating room and then the entire patient journey “from the moment they’re admitted to a bed to the moment they’re discharged,” says CEO McEvoy. But the strategy for engaging additional departments is not likely to change.

“You want to find some good formal or informal leaders, and you want to have a good cross-section of participants,” says McEvoy. “The other thing we discovered very early, right from the beginning with the emergency room, is that you want to have a mix of personality types. That turns out to be very important. If all you have are people that love to go to new courses and love to make change happen, you’ve missed out on the most important ones — so we’ve looked for the ones who are jaded. It turns out that having them participate and engaged was one of the most powerful forces for change.”

Like many hospitals throughout Canada, Hôtel-Dieu Grace is dealing with rising volumes and budget pressures, yet staff have maintained morale reasonably well despite being stretched thin, notes McEvoy. And that’s in an environment, unlike the U.S., where additional earnings from rising volumes cannot be wielded to motivate staff. “We have one fewer lever available to pull to make this work, and that’s driving us to recognize what are the real values of the people that work here,” he says. “We can’t give them bonuses. We can’t hire new people. We can’t increase revenues. We can’t increase earnings. But we can still get people to improve the system.” And, notes Coughlin, “you can make their worklife better.”

“If the providers feel better about their life in the hospital,” adds McEvoy, “the patients automatically do better.”

As helpful as value-stream mapping and other lean tools are to improving Hôtel-Dieu Grace departments and processes, top management realizes the real driver for change is people wanting change, wanting improvement for themselves and their patients. “If you’re the CEO of the hospital and you see lean as a set of tools, it probably won’t work,” says McEvoy. “You have to see way past the tools. The tools are only things you give to your staff who are interested in changing. If you can’t bring them to the point of being interested in changing, they’ll stop using the tools and they’ll go back to the old ways of doing things.

“We’re finding now that we can’t envision the hospital any way other than this,” adds McEvoy. “This is the way it’s going to be. The whole notion of continuous improvement means there is no ultimate state, but there are constantly better states than the one we’re in.”

Learning to See Using

Value-Stream Mapping

Develop a blueprint of improvements that will achieve your organization’s strategic objectives.