Dear Gemba Coach,

How can a narrow focus on problem solving help us to find innovative solutions? Shouldn’t we be looking for disruptive breakthrough instead?

Good point. Problem solving is a tool, not an end in itself. We are looking for breakthrough – the issue is how to get there? Common theory about how we get new “breakthrough” ideas center around the fact that the mind is a loose association machine with no off switch. Discoveries, we’re told, result of either a serendipitous, accidental “aha!” moment, or from mulling through a thought, incubating so to speak, until it finally emerges fully formed. This, indeed, reflects our everyday experience of having new ideas: they either emerge fully formed in a blinding flash of insight, or we worry at them like a sore tooth until, after much consideration, a new shape appears and … eureka!

From this point of view, problem solving seems dry indeed – just fixing issues within the existing process with nary a chance to challenge assumptions and yield new innovative insights.

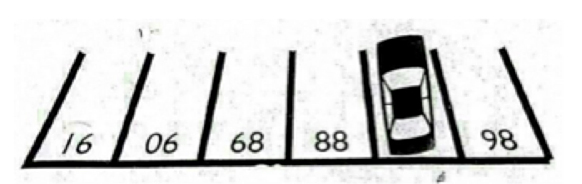

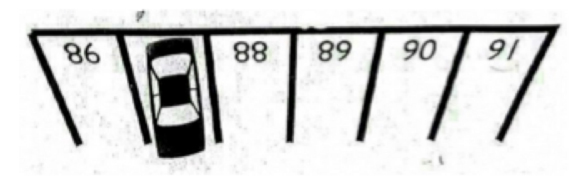

New ideas are often born of reframing – one person has exactly the same data as every one else but somehow looks at the situation differently and comes up with a radically new understanding. There is a magical aspect to reframing which leads us to focus on the “perspective shift” moment. For instance, let us consider this mathematical problem: which number on the series is the car parked on?

16, 06, 68, 88, ?, 98 – which number fits between 88 and 98? Found it? Given up? Now let’s reframe the question:

87. Okay, party trick. Still, this is exactly how reframing works. Charles Darwin doesn’t look at how species evolve through inner forces, but asks himself why all other variants disappear – and realizes that they get selected out. Albert Einstein wonders how the universe would look like sitting on a ray of light, considering that the speed of light should be constant in at any point in any place – hence everything else changes, including space and time, etc.

Insight is generally born from connecting the dots differently. This happens in three broad situations (of course, no two insights are the same):

- New data, information or an idea suddenly connects with what we already know.

- What people tell us of a situation doesn’t square with how we understand the dots connect and we delve and delve until we understand either how what they tell us is wrong or how our own understanding can be corrected.

- We suddenly see an element of the situation we had previously dismissed which, if looked at differently, changes the whole game.

There are probably many other sources of insight, from step-by-step careful analysis to dream messages from the Gods, but my own experience of watching people have new ideas on the gemba tends to reflect either (1) being told something new and connecting the dots we previously had in a new way (VSM often does that, for instance), (2) being certain of a theory and not understanding why it apparently doesn’t work that way in practice (many business issues fall in that category), (3) discovering that a previously minor, detailed, factor is in fact decisive (typical of quality problems).

My point is that whatever the mental mechanism that gets us to connect the dots in a new “aha!” way, we’ve got to know where the dots are first.

Find Fresh Dots

The main emotional drivers to creativity remain curiosity, obsession (and yes, the occasional creative desperation), that makes us continue to gather more facts and assemble the jigsaw puzzle in our minds in various ways until, at some point, things fall in place in a different form. Without the constant urge to collect new facts and observations, as a shell collector on the beach, there is little chance of any insight.

Which is why problem solving is essential. Problem solving is not about solving all problems until the process is perfect, as if taking all the grains of sand out of the machine will make it run perfectly. In real life, problems are confrontations of the way we work with some environmental change – solve one problem, another appears. After parting the seas and getting his people across the Red Sea ahead of the Egyptians hot in pursuit, Moses and his people found themselves … on the wrong side of the Sinai desert.

Problem solving is in fact a device to make people own up to their own experience and confront it to what really happened, here and now. Adults learn from self-reflexiveness on their own experience and figuring out what they know for certain, what remains unclear and where they haven’t got a clue. Without reflecting on our own experience it becomes impossible to break away from it and look for new ideas – as we see in the case of “concrete heads” who will not consider new experiments or new facts, but keep on banging old drums regardless of what happens around them.

Problem solving is the key to examining situations anew, looking for fresh dots, exploring again those we thought we knew and, on good days, triggering new insights.

But, clearly, for this to happen we need to be on the look out for insights and not simply for solutions. Many operational excellence approaches focus too narrowly on managing problems to reduce variation rather than creating the space to think to allow for new ways of looking at the situation as a whole, the doorstep to breakthrough creativity.

Which is why lean thinking leaders use A3s for “universities” rather than just fixing issues.

Ground Work

A university essentially works on cross-presenting one’s findings in exploring difficult problems. If we have a team of seven, for instance, and we hold a university one-hour session every week, one person has seven weeks to fully solve a problem through the Plan, Do, Check and Act phases to present their conclusions and their thinking process to their colleagues. In other cases, if we hold the university session once a month, they have seven months and so on.

These university sessions create the ground work for “connecting the dots” in terms of:

- Self-development: each person gets the opportunity (and incentive) to look at one issue in greater detail and explore alternative ways of solving the problem, including alternative technologies.

- Teamwork: presenting to others creates opportunities to share ideas, facts, and make links that we had hitherto ignored or missed.

Problem solving has to be led – to be productive, the people solving the problem have to feel some creative challenge. Problem solving does not mean problem work around (finding a clever way to avoid the problem) or pushing the problem on someone else.

For instance, the CEO of Proditec, a company that makes high-tech visual inspection machines for the pharmaceutical industry, recalls a time when a Korean customer pointed out that one specific type of defect was not picked up by the machine after the equipment had been installed – at the very end of the sales process.

The customer suggested a classic solution that would solve the problem in 99% of cases, and at the cost of adding a further feature to the machine. The CEO found this fix did not fully solve the problem and was costly.

He therefore pushed his R&D team to look into new optical solutions to solve the problem in 100% of cases without significant increase in cost, by exploring a wide set of cheap cameras not used previously in the company. Solving the problem this way might look harder but they all will learn and will avoid the recurrence of issues the work around fix would cause later down the line.

In such cases, the leadership role is essential to make sure people don’t stop at the first solution that comes to their mind but explore the problem deeply in order to find more innovative countermeasures. In this instance, solving a customer problem leads to innovative exploration – mediated by the CEO’s guidance.

This is typically the kind of topic to be presented as an A3 at the company’s university.

Problem solving leads to innovative solution if it’s not seen as a way to pressure people to fix the problem and move on to the next one, but on the contrary, think deeply about the situation (why? why? why?) and explore innovative ways of solving the problem without investment. Some such new ideas can lead to further insights, and sometimes, to full-fledged innovation, which might then warrant investment.

Ultimately, performance improvement will not result from digging into the backlog of unsolved problems to get to a hypothetical “no problem” state, but by looking mindfully into selected problems to increase the flow of ideas through the organization.