In today’s Post, I’ll add a little more context to yesterday’s interview with Isao Yoshino and offer a couple of takeaways.

First, to quote my own book, Managing to Learn, on what the heck is the A3 process:

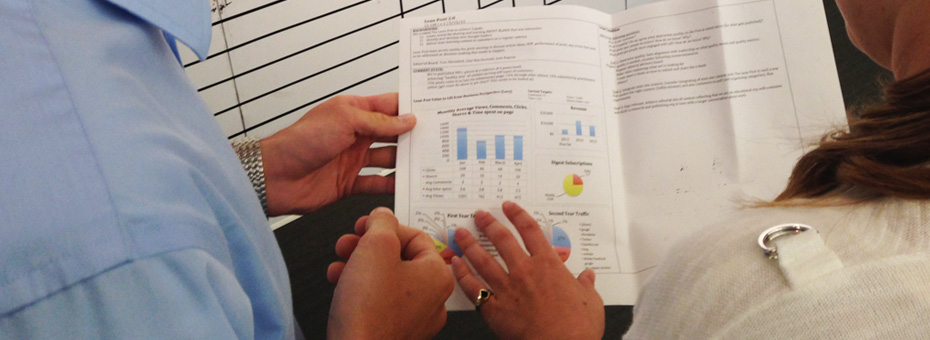

“… the A3 is a visual manifestation of a problem-solving thought process involving continual dialogue between the owner of an issue and others in an organization. It is a foundational management process that enables and encourages learning through the scientific method.”

Were I to rewrite that today, I would change “scientific method” to “scientific thinking.” After all, what we know as the “scientific method” is really just one way of structuring the process of doing science. And science is often a much messier process than is implied by the steps of developing a hypothesis and testing to prove it wrong.

Similar with the A3, I should add. The A3 process isn’t the same thing as science but it’s a process to help teams do science together. Many people think of it as a problem-solving process (or a structure for a problem-solving process) but at Toyota it became much more than that. It came to embody the company’s way of enabling people to work together effectively. Especially in knowledge-work settings – more on that later.

So, is the A3 process the same thing as PDCA? Not exactly. PDCA – like science – can take many forms; in fact, you could call PDCA a structure for doing science. The gemba itself is the best place for PDCA, not a sheet of paper or even the dialogue that the sheet of paper represents. But, in the same way that PDCA is more than the A3, the A3 is more than PDCA. In addition to providing an invaluable structure for PDCA (so that PDCA becomes more than just a nice ideal), the A3 can on a good day embody a holistic way of working together: of mentoring, teaching, coaching, bossing, and helping; of collaborating, aligning, and following-through.

How did the A3 process become so prominent? The A3 became famous when Toyota trainers from Japan used the process to develop their counterparts at newly founded operations around the world in the 1980s and ‘90s. To solve a specific problem, to develop a certain plan, or to align thinking around an emerging issue, Toyota trainers at Georgetown and elsewhere could frequently be heard demanding: “Bring me your A3!”

A little more background from a post I wrote for lean.org in 2008:

“I discovered the importance of the A3 Process firsthand, as do all Toyota employees. In my case, my first managers, Isao Yoshino and Ken Kunieda, and co-workers desperately needed me to learn the thinking and gain the skills so I could begin to make myself useful! But, the Process I went through was in no way special. When I joined Toyota in Toyota City (where for a time I was the only American) in late 1983, every newly hired college graduate employee began learning his job by being coached through the A3 creation Process. The new employee would arrive at his new desk to find waiting for him a problem, a mentor, and a process to learn for solving that problem. The entire process was structured around PDCA and captured in the A3.”

I didn’t know at the time how the A3 process had become such a fundamental management tool for the company, used to develop skills in problem solving and proposal generation, to create alignment – to embed PDCA deeply in the management environment through a structured process of mentoring, teaching and coaching. That’s where the Kan-Pro initiative comes in. Thank you, Mr. Yoshino, for sharing your personal experience with the program that did so much to entrench the A3 in Toyota’s culture.

But, looking back almost 40 years later at Nemoto and Yoshino’s Kan-Pro initiative, it is instructive to note that Toyota’s focus was on managers of what we now call knowledge work.

The Kan-Pro program included all mid-level managers EXCEPT (!) those who led operations at a direct-production gemba site (notably, sales and marketing folks were also excluded, simply because Toyota was split into two companies – manufacturing and sales – from 1950 to 1982). The best canvas for PDCA is ordinarily the gemba itself. When Nemoto and Yoshino executed Kan-Pro, Toyota figured that production managers didn’t need and didn’t have time for the A3 development exercises. Note, however, that production ENGINEERS – who DO take time to sit down and plot the future – WERE included in Kan-Pro.

The same truth – that gemba is the best canvas for PDCA – can hold for other types of work as well, of course – that is, IF we structure the work with that intention. That’s what the obeya is all about, as an example. Or any kind of visualization board, of the type that is common in many companies nowadays (Menlo Innovations and Nationwide Insurance are two companies that have shared useful office work visualization examples at recent Lean Transformation Summits).

As knowledge work takes over economies, making sense of it naturally grows in importance. Hence the rise in prominence of applications of lean thinking to knowledge work, such as Jim Benson and Tonianne DeMaria Barry’s “Personal Kanban;” Matthew May’s “Winning the Brain Game;” and Parry’s “Sense and Respond.” Note also the relationship of all this to habit-forming routines, such as Mike Rother’s “Toyota Kata” or Charles Duhigg’s “Power of Habit” or more recent “Smarter, Faster, Better.”

Or, for a more academic view, recall Ikujiro Nonoka’s “The Knowledge-Creating Company” in Harvard Business Review from 1991, or more recently, the spring Sloan Management Review article by Michael Ballé, Jim Morgan, and Durward Sobek on “Why Learning is Essential to Sustained Innovation.”

Okay, what’s the point of all this; why this walk down history lane? First, I do think history can be instructive (I don’t buy Henry Ford’s “history is more or less bunk” theory) and Mr. Yoshino was eager to share this little-known but important story. Secondly, Kan-Pro speaks to the need for any company, for all of us, to be deliberate in the development of management skills and thinking. Too many companies still act as if all they need to do is hire great people (“get the right people on the bus!”) and turn them loose (“people have natural talent, just get out of the way!”). That may sound attractive, but I haven’t seen it work. If we want certain capabilities and behaviors, better to be deliberate about developing them. No?

Thirdly, as the percentage of the work we all do resides more and more in this realm of “knowledge work” (I don’t know about you, but I’m not building any cars here at LEI’s office in Cambridge, Mass.), the need to understand and improve this type of work becomes increasingly important. The design of the work experience should be deliberate, whether the work is physical or mental. Kan-Pro was Toyota’s first attempt to tackle this thorny topic in a deliberate way.

Oh, and one final note. Never to forget: the A3 is not the point. The point is the science. The PDCA. The problem solving. And the improvement and the learning.