Dear Gemba Coach,

Should I bother reading lean books, or just work from experience? There are so many books, and they seem to contradict each other. Which ones should I start with?

All of them! Not kidding – all of them! Not all at once, obviously.

In the long years I’ve been working both with executives and lean experts, if you’d ask me for just one key success factor, I’d say … reading. The most successful people I know read. A lot. Of everything.

Since none of us has a crystal ball or a magic mirror. The only answer to discover our own false beliefs is to read the beliefs of others – all of them.I know this sounds glib, but let me get into the technicalities of it. It’s easy to agree that no one person has the truth and that we are all expressing a point of view, influenced by our “angle of view” (what we look at and from which perspective) as well as implicit biases we’re probably not that aware of. It doesn’t mean that what we say (or indeed, write) is wrong – though sometimes it is – it means it’s partial.

Two key cognitive features human children develop very early on, and that largely escape (as far as we know) other animals are:

- Shared intentionality: The ability to understand what others are trying to do and join in (or hinder);

- Recognizing false beliefs: Recognizing in others and in oneself that some of the things we believe are true simply ain’t so.

When you think about it, both features are rather astonishing and linked. Recognizing false beliefs comes from recognizing joint goals, and thus seeing that some people get their facts wrong. Reading intentions, goals and beliefs in people’s action is key to developing shared intentionality, so these traits go together.

What is fairly easy to do with concrete actions such as, looking for mushrooms in the woods (“don’t go there, you think there are some but I’ve already been there and picked them all”), becomes really complex when talking about larger, abstract goals, such as “let’s do lean.”

My Personal Bias

What exactly is “lean” in the first place? My definition of lean is applying the lessons of Toyota circa. 1965 to other companies. Others would say lean is a method for the systematic elimination of waste (I don’t disagree). Or that it’s the process of sustaining lean thinking (whatever that is). Others will say “let’s forget about lean, practice kata instead” – and yes, that’s lean. Most would say “let me practice the tool that I like and see where this gets me,” and so on.

When looking at lean, all of us have:

- A starting point: Our experience with both lean and non-lean stuff

- An angle: Something that we look at or want to do

- A reason: Pressure from the outside world to deliver

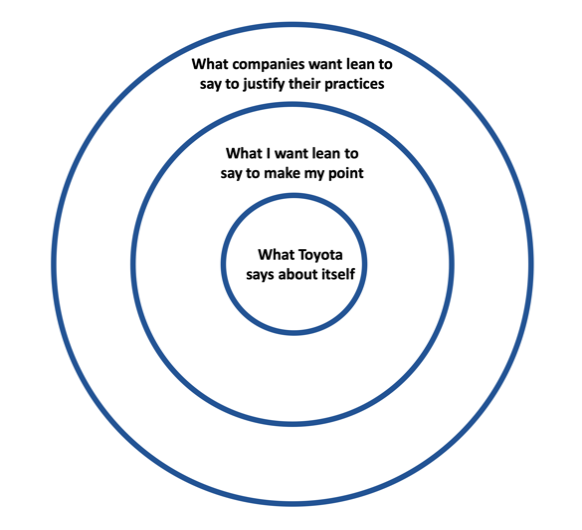

For instance, my personal bias about lean looks something like:

With this framework in mind, I can have some idea of where the person is starting from, which way they are oriented (towards Toyota or towards something else), and so better understand what they’re touting.

A book, in effect, is a long-winded, detailed and illustrated justification of what the person thought, saw, and wants to explain. As such, any book is rich in:

- Intentions

- Practices

- Beliefs

Fake News

Since none of us has a crystal ball or a magic mirror. The only answer to discover our own false beliefs is to read the beliefs of others – all of them. It’s not by chance that Taiichi Ohno, one of the founders of lean thinking, starts his own book on Workplace Management by the proverb “even a thief is right three times out of ten.” If that’s true, Ohno reasons, we should expect a normal person to be right half of the time and wrong the other half. Trouble is we don’t know which half.

The lesson here, if you are sincerely interested in distinguishing true beliefs from false beliefs, read thieves’ books and look for intent.

False beliefs are incredibly sticky in adults. Cognitive dissonance – our ability to choose opinions that fit our worldview and goals over facts – is one of the most tested and proved mechanisms of social psychology. False beliefs are hard to change largely because they support intentions, and, well, we want to do what we want to do.

The only way to explore one’s own false beliefs is to accept to participate in someone else’s intentionality, something that becomes harder and harder as we gain experience. After all, we know what we stand for and where we want to go. Why should we listen to our opponents? Because … they still might be right three times out of ten.

If you only work through experience, you’ll never look outside of your own intentionality and core beliefs. Motivated thinking is a core feature of human thinking – you’ll only pick the facts and the conclusions that fit your intent and your conclusions (why experts are soooo bad at predicting the future – read Tetlock). Looking at your experience without throwing at it others’ intentionality and beliefs is simply wasteful – and ultimately self-defeating.

Which is why we need to read all of them. We don’t have to finish them. We don’t have to give them deep thought. But we need to open them and give them a chance.

Where should we start with? As with any field, read the founders. Read Taiichi Ohno, Read Birth Of Lean, read Womack and Jones. Read Jeff Liker. Look for facts, for sure, but beyond facts look for intentionality: what was their problem at the time? How did they describe it? What did they see others didn’t? What did they miss? What did they discover? How did they do so?

For instance, my own personal learning from reading the early texts is realizing how much lean thinking started with kanban and quality. As a result, I taught myself both subjects and now firmly (maybe falsely) believe you haven’t experienced lean if you haven’t set up a kanban (whatever the shape of it) and if you can’t distinguish a true kanban (pulls from customers from a false one (pushes from our own internal work organization). The same thing with quality, you haven’t experienced lean if you can’t distinguish a quality loss function, beyond “solving problems.”

But that’s just me – and that’s my point. This is someone each of us needs to figure out on their own.

Lean is still in Day One. There are hundreds (thousands?) of lean books out there, and yet people who truly grasp lean practice are still rare and far between. You want to become one of them? Read all the books. Try stuff. Read more. Talk to others on the same path. You’ll be astonished at how fast this will accelerate your learning curve. As Sakichi Toyoda admonishes us beyond the grave: Open the window. It’s a big world out there!