I found all of the elements of standardized work — work standards, work combination tables, kaizen opportunity lists — clearly posted in work areas, but no standardized work and no standardized front-line management. A few minutes’ observation revealed that the work was not actually being done in the way the work standards required…

–Jim Womack, Gemba Walks, p. 76, “The Mind of the Lean Manager” essay.

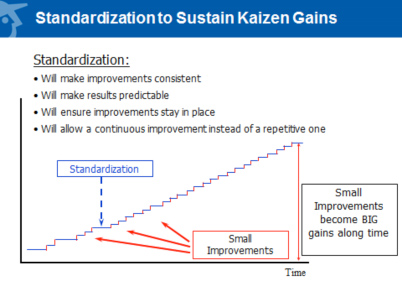

Establishing and following standardized work is an essential part of any lean transformation, serving as the foundation for kaizen. But in practice, many organizations struggle with issues of leadership, culture, and resistance when implementing or sustaining standardized work.

“The major challenge is convincing people to accept standardized work,” says Sammy Obara, a Lean Enterprise Institute faculty member and managing director of honsha.org, a San Diego-based lean consulting group comprised of former Toyota employees.

The [surfing] culture was averse to a standardized approach. For example, they didn’t want to wear watches because they believed they could manage just as well by watching the sun.

Standardized work consists of a detailed, documented, and visual system that serves as a blueprint for people to follow to perform tasks in a predefined process. Typically centered around human movements, standardized work outlines efficient, safe work methods that help eliminate waste and serve as the baseline for kaizen, or continuous improvement.

Standardized work documents the current best practice, and as the standard is improved, the new standard becomes the baseline for further improvements.

In practice, some groups tend to be more open, while others are more resistant, to accepting and embracing standardized work. Not surprisingly, Obara has found that military organizations are among the best at following strict standardized work methods. Employees of pharmaceutical firms also tend to more readily accept standardized work, perhaps because they are accustomed to following the requirements of the Food and Drug Administration.

Overcoming Resistance

“In my experience, among those least likely to accept standardized work are surfing instructors who tend to be free-spirited in the way they approach their work,” says Obara. He speaks from the benefit of experience, having worked with the Pacific Surfing School (PSS) in San Diego to instill standardized work among the school’s dozen or so surfing teachers. “Realistically speaking, having surfers adhere to a more regimented procedure, where you have to respect standards, times, requirements and expected outcomes, is a miracle in itself.”

Surfers tend to take a loose, relaxed attitude toward the sport, so anything that smacks of regimentation naturally would be hard for them to swallow. “The culture was averse to a standardized approach,” Obara says. “For example, they didn’t want to wear watches because they believed they could manage just as well by watching the sun.”

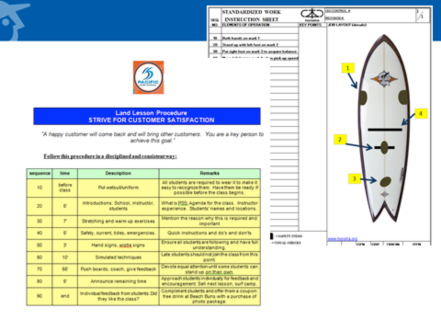

After carefully observing the entire process of how PSS taught people to surf, Obara was able to break it down into half a dozen parts that made up a one-hour session:

- Fitting (boards and wetsuits);

- Communications (introductions, safety briefing, hand signs, whistle signs);

- Exercise (stretching);

- Land surfing (simulation);

- Rowing (getting out to catch a wave); and

- Surfing!

The first five steps took up so much of the hour session that when Obara clocked the time one surfer spent actually surfing, it was a total of five seconds standing up on his board on three waves.

3 Main Elements of Standardized Work

- Takt time, which is the rate at which products must be made in a process to meet customer demand.

- Precise work sequence in which an operator performs tasks within takt time.

- Standard inventory, including units in machines, required to keep the process operating smoothly.

For example, fitting took 10 minutes. As the dozen students Obara observed scrambled among one another to find the best-looking suits, some got the wrong size, boys got girls’ suits and vice-versa, while others got wetsuits that were still wet from previous use.

He suggested organizing the wetsuits in advance, assigning each student his or her own suit on a dedicated hanger so it could be picked up before the start of class. As a result, they were able to add 10 minutes of actual surfing time to the end of the lesson.

For the land surfing component, instructors showed each student where to place their feet on the board during each maneuver– i.e., getting up on the board, standing, acquiring balance, and finally picking up speed. Having placed one or both feet only a few inches to the left, right, forward or to the rear of the correct position often resulted in a wipeout once they stood and attempted to balance on the board.

Students had to repeat this 10 times, each time going from lying on the board on the sand in a simulation routine, to the standing position on the board. Some students would get their feet in the right places the first time, but most had to be shown where their feet belong.

Too much variability in foot placement on the board resulted in a student failing to get up. “If they couldn’t stand up on a board at the end of the class, they would get a free follow-up class,” Obara says. “Our solution was to put marks on the boards so the students could self-check the placement of their feet when doing this simulation exercise 10 times.”

Leadership by Example

The owner of the surfing school, Emiliano Abate, convinced his people that the organization would fail if they did not implement standardized work, Obara says. “His leadership played a key role in getting people to follow his example and his commitment to standardized work,” Obara adds.

“The key ingredients that made this a success in my school were the example that we — the senior instructors and myself — showed the rest of the team,” Abate says. “And it was important to continuously ensure compliance to the new standards, which in the beginning had their share of resistance from the instructors.”

In the communications segment, instructors had different approaches to introduce all the students and themselves. In fact, the variability of instruction techniques used by the teachers afforded plenty of opportunities for improvement by applying standardized work.

Adapting the Principles

“The key was to look at this type of business from a somewhat similar angle that manufacturing does,” Obara says. “I soon realized that the best perspective was to see students as the raw materials coming in, and an hour later, finished goods going out the door as surfers. The school was the factory and the instructors, the processes. The batch was about 12 students per session — like a dozen in a box. So takt time, one of the three key elements of standardized work, would have to be 60 minutes divided by 12, or five minutes per student. Takt time is calculated as available time divided by customer demand.

|

“The big difference here was that only the sign-up, dressing, and payment processes were done individually. All other processes were done with the entire group. Since the group lesson took 45 minutes, the other 15 minutes had to be divided equally among all students at a pace of a little over one minute per student, including complete registration and waiver, execute payment, and fit the wetsuit.”

Working sequence is another element of standardized work that Obara was able to apply to the freewheeling surfing instructors. “We made changes to the layout and to the lesson agenda,” he says. “To comply with the takt time, training boards had to be re-laid out, registration forms simplified, the registration desk repositioned, and the written instructions and exercises redistributed along with the agenda.”

“The third element of standardized work we used was standard in-process stock,” Obara says. “Although stock is considered one of the seven wastes, sometimes it is necessary so we can reduce walking, waiting, and/or some other wastes.”

In this case, the standard in-process stock turned out to be surf boards and students. Boards chipped or damaged in a class previously were set aside for repairs so they could be used again the next day. Now, instead of retiring the damaged boards for the entire day, instructors fix the boards as they come back, to be put in use at the next session that day.

Similarly, when too many students signed up for a class, those who could be flexible with their time became standbys, waiting for the next available class. In exchange for waiting, they got a half hour extra time on the board.

“That was a way to eliminate wait, either for the boards or for students,” Obara explains.

Surfing Culture Gets Discipline

In this case, standardizing the work of instructors instilled discipline in the surfing school’s culture, an essential element for lean to take root, flourish, and be sustainable.

“I would never have imagined that lean and standardized work could have such a huge impact on my surfing school,” Abate says. “I was skeptical in the beginning, but I just forced myself and required my team to do the same and give it a try. Once we started seeing the results, it was impossible not to believe in it and embrace it fully.”

|

Once standardized work was fully implemented, the students had more time to surf at the end of each class, which freed instructors to do other tasks, such as repairing surfboards that had been damaged during use so they could be reused the next session. In the past, the only time left for this task was at the end of the day after classes were done. The problem was, with the waning daylight, some boards got only partially repaired, or poorly fixed at that.

“Now the instructors had time to fix the chips on the boards during daylight hours,” Obara says. “This gave them more time to do marketing for the school, so they could go to the boardwalk and distribute flyers to increase demand.”

By having a more efficient, standardized work routine, instructors were able to boost the number of students per class from 12 to 18. This increase in capacity was matched by a similar increase in demand due to the expanded marketing efforts of instructors. Overall, Abate reports, the end result has been a revenue gain of about 85%.

In other words, overcoming resistance by ensuring that leadership and culture of an organization are fully committed to standardized work pays off in more ways than one.

Next Steps

Hear from Emiliano Abate, owner, Pacific Surfing School, on standardized work.