Standardized work is foundational to the Toyota Production System, yet remains one of the most misunderstood principles to outsiders. It is crucial to understand the true purpose of this foundational practice. Standardized work in the context of the Toyota Way refers to the most efficient and effective combination of people, material, and equipment to perform the work that is presently possible. “Presently possible” means it is today’s best-known way, which can be improved.

Like so many organizational practices, Toyota has turned the practice of standardized work on its head. In the early days, armies of Tayloristic industrial engineers roamed the factory, timing workers and imposing on them “the one best way,” which led to performance standards they were judged against. It was coercive, and workers and unions fought against it or used it to place a cap on the work pace. Toyota turned standardized work on its head and made it a tool for work groups to control and improve their work. In Paul Adler’s terms, it became part of “enabling bureaucracy” rather than “coercive bureaucracy.” Rather than forcing rigid standards that can make jobs routine and degrading, at Toyota, standardized work is the basis for empowering workers, sharing ideas for improvement, and driving innovation in the workplace.

Standardized work refers to the most efficient and effective combination of people, material, and equipment to perform the work that is presently possible.

The critical task for standardized work is to find that balance between providing employees with rigid procedures to follow and providing the freedom to innovate and be creative in consistently meeting challenging targets for cost, quality, and delivery. The key to achieving this balance lies in the way people write standards, as well as who contributes to them.

First, the standardized work must be specific enough to be a useful guide, yet general enough to allow for some flexibility. Repetitive manual work can be standardized to a high degree by detailing sequences of steps and times. On the other hand, it would not make sense in engineering to specify a step-by-step way of performing the work. There are general plans with milestones, and then technical information about the product that appears in engineering checklists. For example, knowing how the curvature of the hood of a car will relate to the air/wind resistance of that body part is more useful than dictating a specific parameter for the curve of all hoods. In product development, this is often represented as trade-off curves.

Second, the people doing the work are in the best position to improve the standardized work. There is simply not enough time in a workweek for industrial engineers to be everywhere writing and rewriting standards. Nor do people like following someone’s detailed rules and procedures when they are imposed on them. Imposed rules that are strictly policed become a source of friction and resistance between management and workers. However, people happily focused on doing a good job appreciate getting tips and best practices, particularly if they have some flexibility in adding their own ideas. In addition, it is very empowering to find that your team is going to use your idea as a new standard. Using standardization at Toyota is the foundation for continuous improvement, innovation, and employee growth.

Using standardization at Toyota is the foundation for continuous improvement, innovation, and employee growth.

In her book Steady Work, author Karen Gaudet shared that she learned about standardized work at Starbucks, giving a very different picture from the Tayloristic view of people as erratically functioning robots:

“Humans just are not hardwired for repetition, it seems. And in service industries, quality human contact is central to the work. Human contact and standardization can seem like oil and water. But here is the truly important discovery from our observations: when task standardization is adopted and steady work cadences are achieved, people are freer to do the satisfying work of making human connections. When work tasks are both repeatable and rote, managers, executives, and frontline baristas all have more space in their lives to chat a little, to ask questions, and to listen to others.”

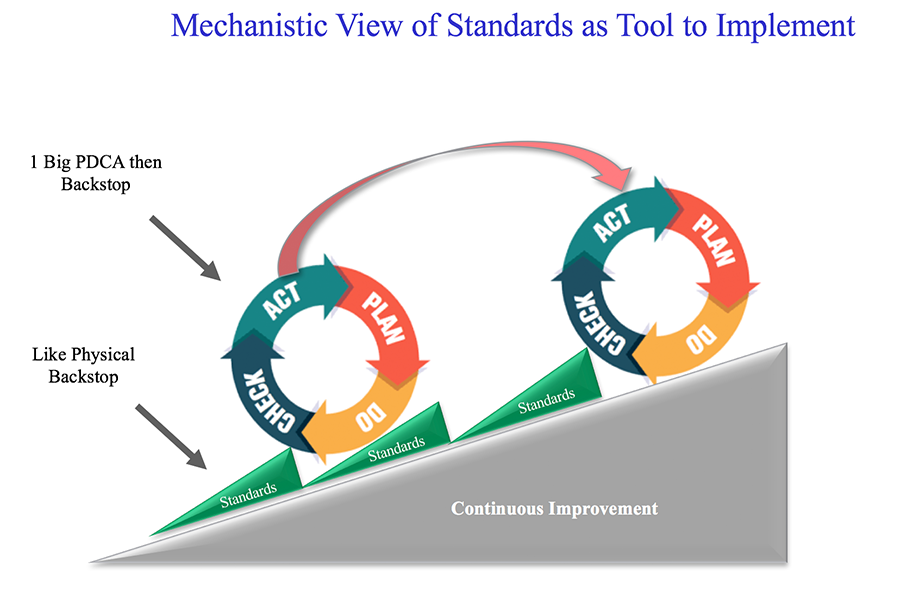

I think the problem with how many organizations use standardization results from our old nemesis, the mechanistic perspective. When the organization is viewed as a machine, then standardized work is a tool that is intended to make it a better machine. The figure below presents a common graphic in lean training that shows standards as backstops. You figure out the best-known way to do the job, write out the worksheet, teach it, and then shove the standardized work in place to prevent the process from slipping back. This approach ignores the fact that it is the person who can slip back, not the process. People have a way of doing the work they are comfortable with, and developing any new habit takes repetition—and practice.

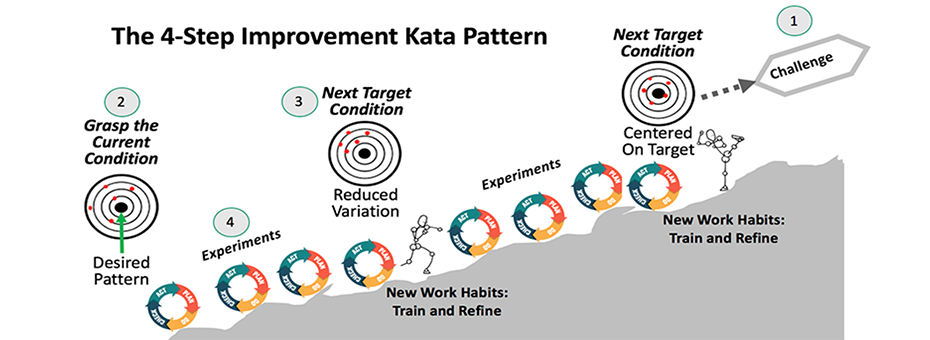

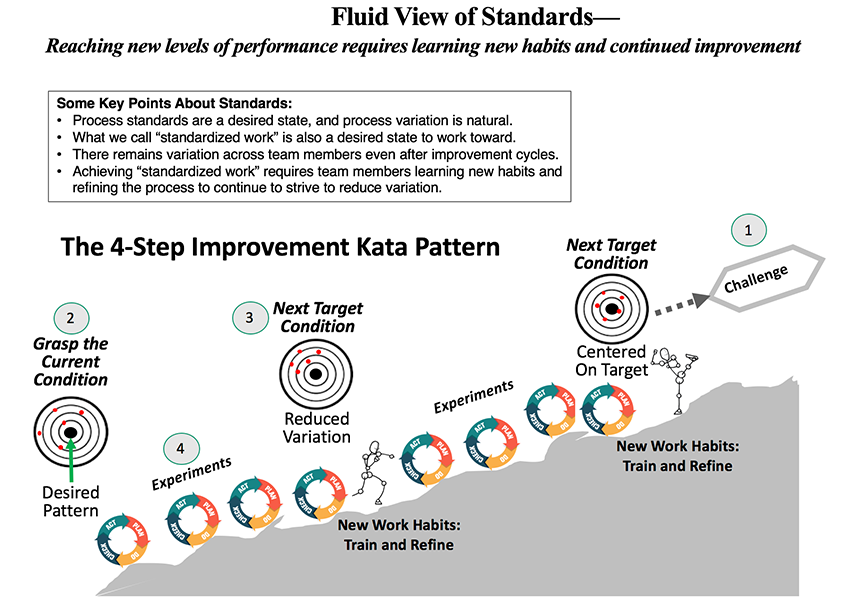

The following figure presents a more dynamic, fluid view of standardized work that recognizes the time and effort required for humans to learn a new way of doing things. In this case, I used the model of improvement developed by Mike Rother that is part of Toyota Kata. Kata are ways of doing things in the martial arts that you have to practice repeatedly with a coach to develop the skill and reduce variation. Kata also form the basis for job instruction training, practicing small pieces of the job repeatedly with a coach. The ideal state is to have standardized work that is practiced consistently by people, coupled with step-by-step improvement through rapid PDCA cycles. The next level of performance can be thought of as a “target condition” that people need to strive for. You do this by experimenting with different methods for doing the work, and then when a performance threshold is achieved, you document the process and teach it as the best-known way at that time. You turn the standardized work document into consistent behavior through job instruction training, which develops the new habits through repetition. Then the work group starts on the next lap with the next target condition (level of performance), experimenting and finding a better way. In this way standardized work and continuous improvement become two sides of the same coin.

Standardized work can be an ugly thing in the hands of control-oriented bureaucrats and a beautiful thing when it enables creativity and continuous improvement. Enabling bureaucracy takes more effort, but it is worth it.

(This article is adapted from Jeff’s recently published The Toyota Way 2nd Edition: 14 Management Principles from the World’s Greatest Manufacturer.)

Improvement Kata/Coaching Kata

Develop Scientific Thinking, a Foundation of Lean Management in the 21st Century.