At the Cleveland Clinic, where I work as medical director of continuous improvement within the President’s Office, we think a lot about how to cultivate a problem-solving mindset and to build a culture of improvement across our organization, “every caregiver, every day.” We are often asked a basic question about this work:

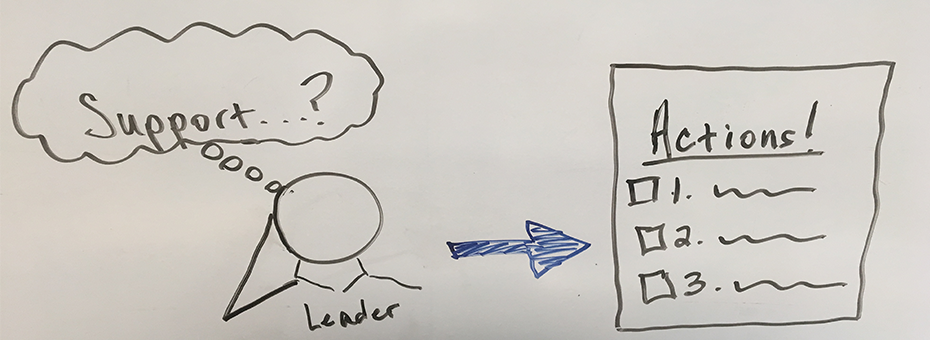

“How do you get leadership engagement/buy-in/support?”

Many people in the Lean community understand that leadership commitment is a key success factor in this work, and are working to gain that commitment. However, I have never heard a clear answer to this question (has anyone?). This may be because – as is often the case in Lean dialogue – there is no single, clear answer. I suppose it depends on the specific situation: what exactly is the problem you are trying to solve? Sometimes we find it helpful to hear how someone else is approaching a problem, and for that reason, I share how we (CI Senior Director Nate Hurle, the CI team and I) are thinking about this in our organization.

- We don’t ask for “support.” Or “buy-in.” These terms are vague and subjective. Instead, we make our requests clear, specific, and purposeful. Vague requests can lead to several potential outcomes – generally not ideal. The first (and probably most helpful) is a “no” response. While disappointing, it is direct, honest, and sets clear expectations. That clarity can drive some A3 thinking. The second potential response is a lack of response. Perhaps initially less clear, but in reality – pretty clear. Back to the problem solving. The third option – and probably the riskiest – is a “yes.” Although this may appear to be good at first, this scenario sets both parties up for disappointment. Invariably the leader and the requestor don’t have the same idea of what exactly support means. So the leader does what he/she believes is “support” while the requestor does not experience what he/she believes is support. Disappointment, hard feelings, and drama ensue when one party feels that “support” is being provided, and the other does not.

Instead, we aim to make very clear, specific asks.

When we first started our work to build a culture of improvement across the Cleveland Clinic, we built one “model area” intended to be a model for the culture we desired (“every caregiver capable, empowered and expected to make improvements every day”). Then we engaged each executive leader with one clear, simple ask: “Can we set up 30 minutes to talk with you about something we’re working on?” Not a single leader declined this request. - Now that you have a clear, specific commitment, how exactly will you engage? What will this work call for in specific and tangible actions? In these initial discussions (and in many of the conversations I have …), I approach the conversation through the left side of the A3. Start with the purpose. Why are we even talking about this? Why is this an important problem to solve? What is the target condition? What do we know about the current state? What is the clear, specific ask to them to help forward your A3? The help you seek could be in any part of the A3 – further defining the target condition, confirming or editing the current conditions, or reviewing potential countermeasures for input and feedback. Prior to the meeting, think about your next clear, specific ask. What specific action do you most want that leader to commit to? For us, we used the initial 30-minute meeting as a lead-in to our next clear, specific request – will you commit 1 hour to come see it? This request was important because …

- We don’t ask for anyone to “support” something they haven’t yet had the opportunity to experience, understand, and critically evaluate. We want our leaders to make good commitments, and that can only be done when they understand what they are committing to, and why. It would be unwise to agree to support something I don’t understand, and I would not ask that of my leaders. Colloquially we compare this type of request to a marriage proposal on the first date. You may get a yes, but do you really want one? Asking for a gemba walk provides an opportunity for the leader to learn about the target condition (for us, a culture of improvement – every caregiver capable, empowered and expected to make improvements every day) in the best way we know-how—through experience. Through the gemba walks, leaders began to build an understanding of what a culture of improvement looked like. They would begin to understand the commitment, the capability built across the team, and the impact on as well as the impact of engagement in both in terms of results.

We first used these steps in 2013 when we started to build our culture of improvement, and Executive Chief Nursing Officer Kelly Hancock was one of the first leaders to say “yes” and then “yes” to these first two asks. After her first gemba walk, she turned to me and made a very clear, specific ask. “I want you to help us do this in Nursing.” That’s a clear, specific commitment I can make.

Great article Lisa, thank you for you insight and leadership. We are going use these tips and ideas in our CI work.

Wadie Shabab