Lean practitioners understand the need to reflect on or check what they’ve done as part of a lean improvement cycle, but sometimes it’s as — or more — critical to focus on the how. Still, reflecting on the actions taken to improve a work process, while essential, is an often-overlooked practice — and reviewing how leaders led the change, arguably more vital, is even rarer. That requires an in-depth look at how leaders interacted with their direct reports to influence the change. Because how leaders lead a lean improvement cycle matters. Did they coach or command? Show respect or disdain — or worse, indifference? Help employees build their capabilities or merely meet the objective?

How leaders lead a lean improvement cycle matters.

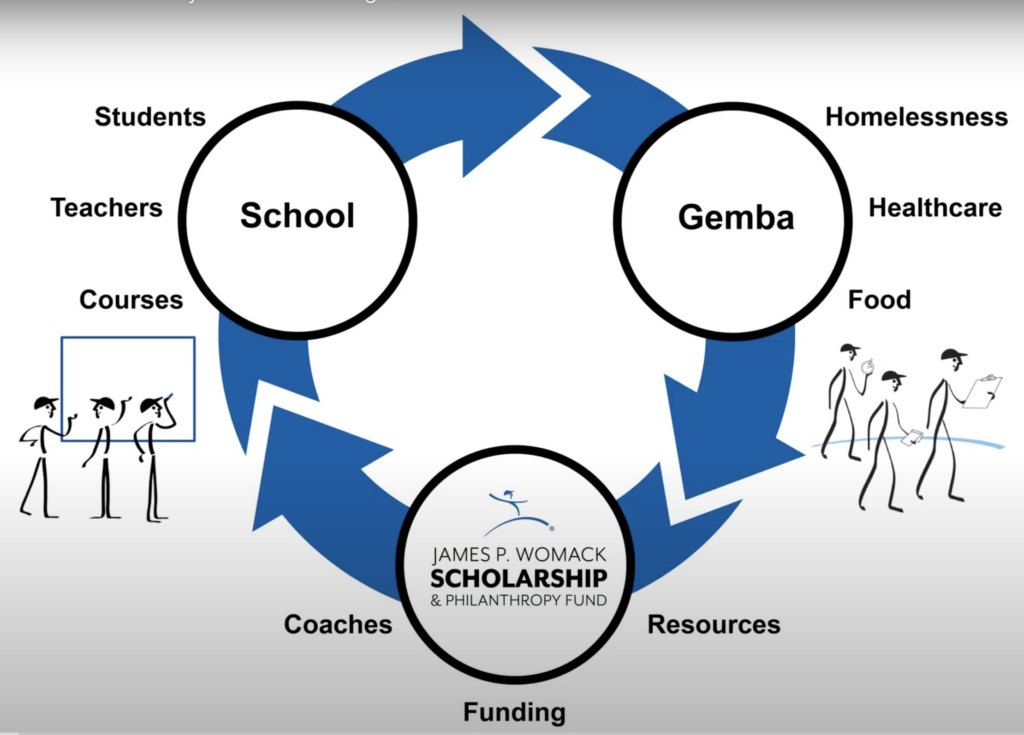

Having reflected on the accomplishments of the first wave of interns sponsored by the James P. Womack Scholarship & Philanthropy Fund, the JPW Fund internship leaders are looking deeper into the coaching. Specifically, they’re exploring the specifics of the interactions between the coaches, interns, and host organization’s staff who worked together in what was a learning experience for everyone.

Determining the Problem and Purpose

When JPW Fund leaders started planning an internship program, they sought to offer students opportunities to practice lean thinking in situations where the outcome matters rather than in simulations in a classroom. The problem to solve, they determined, was to figure out how to teach lean thinking and practices during the college years, so hiring companies wouldn’t have to reeducate (read: rework, the worst form of waste) students steeped in traditional management and work practices. Then, to connect that mission with LEI’s broader vision of “making things better through lean thinking and practice,” they stipulated that the program would place students at community-service organizations (CSOs), the often money- and time-starved nonprofits dedicated to helping others. The idea was that not only would the interns gain experience with lean thinking and practices, but the CSO staff would also learn and be encouraged to adopt them.

… not only would the interns gain experience with lean thinking and practices, but the CSO staff would also learn and be encouraged to adopt them.

In a couple of experiments to test how this approach would work, the JPW Fund leaders sponsored internships in partnership with two universities: one at Oakland University’s Pawley Lean Institute (OU PLI), Richmond Hills, Michigan, and the other at the California Polytechnic University in San Luis Obispo. For the OU PLI internships, LEI Coaches Matt Zayko and Eric Ethington — with 25 and 30 years of experience leading lean transformations as executives or coaches, respectively — donated their time to guide the interns. First, Zayko coached four intern teams at Humble Design Detroit, a nonprofit that furnishes homes for individuals and families transitioning out of homelessness. Then Ethington stepped in, coaching the fifth semester at Humble Design and the first intern team at another nonprofit, Leader Dogs for the Blind, a guide dog training organization located in Rochester Hills. (Eric O. Olsen, a professor in the Industrial Technology department at Cal Poly’s Orfalea College of Business who teaches lean thinking and continuous improvement courses, coached the Cal Poly team at Transitions-Mental Health Association.)

The LEI coaches work in tandem with the interns’ academic coach Bill Edwards, an instructor in OU’s Industrial and Systems Engineering (ISE) department with 20 years of industry experience. Also, the CSO leaders work with the interns on location.

This review focuses on three interns (two internship teams) from OU’s ISE program: Carly Kallen, currently a manufacturing group leader intern at General Motors’ Lansing, Michigan, facility, who graduates in December, interned at both Humble Design and Leader Dogs for the Blind; Lauren Woolford, who joined Flat Rock, Michigan-based KLA as a data analyst in April (right after graduation), interned at Humble Design with Kallen (and at a JPW Fund-inspired internship at Fleece and Thank You); and Ryan Shore, an industrial engineering intern at BorgWarner, who will graduate December 2025, interned with Kallen at Leader Dogs for the Blind.

Managing the Work

Generally, the interns spend the first half of the 10-week internship identifying the problem they will address and concentrating on the thinking required to identify and fully understand its root cause. During this time, the interns work to deeply understand the situation, determining the improvements that would have the most significant impact.

“We like the lean terminology, ‘decide slowly, implement quickly,’” Edwards explains. “So, we spend a lot of time in upfront thinking — go and see for yourself, put your own eyes on it, get that better understanding, understand it deeply. And then when you’ve thought it through well enough, it becomes time to execute.”

Chief among this discovery or learning phase is taking the opportunity to join the workers in doing their work to experience it firsthand. For example, Kallen and Woolford helped with a Humble Design home setup and move-in reveal. And Kallen and Shore completed — and watched others complete — the Leader Dogs for the Blind “puppy raiser” online application they were working to improve.

“We encourage them to do the work with each person they worked with and see it firsthand,” Zayko explains. He adds that it is vital for students to learn that to “go and see” not only helps you deeply understand the work process but also shows respect to the people who do it. “When you’re advising people on how to improve their work processes, if you’re not doing the work yourself, it’s a disservice,” Zayko says. “It’s disrespectful.” Additionally, combined with a clear grasp of the organization’s mission, understanding the work that goes into fulfilling the organization’s mission in detail — at the task level —helps improvement teams decipher value-added from nonvalue-added work.

Then, following the midpoint review, the interns implement the countermeasures and create related materials to help the staff sustain the improvements. The latter included such activities as printing and posting signage, marking aisleways with tape to visually indicate storage boundaries, writing standardized work, and the like.

Going to the Gemba

How vital it is to take the time to gain an in-depth understanding of which problem to address was especially evident in Kallen and Woolford’s semester at Humble Design. “We interviewed everyone and anyone — designers, movers, the operations people. Kallen recalls. “Next, we [looked at] what it’s like when they get donations and how that gets unloaded. Then we saw [the designers’] process of picking out and staging items,” she adds.

“We followed them [the designers] around the warehouse to see what their process was, because our original thought was, ‘how can we help them organize this warehouse to make things better for them?’” Kallen explains, adding that they spaghetti-mapped the designer’s movements through the warehouse.

Having considered ideas about how they could streamline the designers’ work, the interns asked a designer whether they could send the bar stools, rarely used in home setups, to the auxiliary warehouse. The designer’s reply was a question: “Have you ever seen the other warehouse?” Since they hadn’t, they went to see it.

“Once we saw the other warehouse, that [original plan] was out the door,” Kallen says. They found the place in such disarray that they didn’t need any other lean practices or tools to decide what to do next. “So that’s when we said, ‘we gotta do a 180 here and see what we can learn about this and what we can do with this,’” she recalls, adding that further investigation revealed other problems.

We could have left the warehouse alone and stuck with our original idea, but what impacted the designers and the company more was definitely that second warehouse.”

Carly Kallen

“We interviewed the designers again, asking ‘how do you feel about the second warehouse?’ and they said, ‘we don’t like going there.’” They also learned “that since there was no mattress organization over there, they never knew if they had enough mattresses — and there was no way to know because the mattresses might be buried under a couch,” Kallen explains. “So, we said, there are a lot of problems with this. Let’s focus on this. We could have left the warehouse alone and stuck with our original idea, but what impacted the designers and the company more was definitely that second warehouse.” She added that Humble Design staffers “were totally open” with them changing where they would focus their improvement efforts.

So they focused on completing a 5S activity at the warehouse, cleaning and standardizing locations for everything, then applying visual management — hanging up signs and taping off the floor — so the staff could sustain it.

Focusing on Lean Thinking

Since the students had been introduced to the various lean tools and their uses in the classroom, the JPW Fund coaches focus their guidance on encouraging lean thinking. Though the interns use tools and practices, “the coaching is more on developing the thinking and the thought process, their kaizen mindset, than [teaching] a specific tool,” Zayko explains. For example, the first pair of interns he coached at Humble Design used A3 problem-solving to winnow the myriad improvement opportunities to the most critical — the ones that would have the most impact within the 10-week timeframe. They also created value-stream maps to help them visualize problem areas.

Though the interns use tools and practices, “the coaching is more on developing the thinking and the thought process, their kaizen mindset, than [teaching] a specific tool.

Matt Zayko

“One of the things that I coached the students on is, just because you have the tool doesn’t necessarily mean you need to use it,” Edwards says. “You need to use the proper tool for the proper job.” For example, with that first Humble Design team, their role “was very exploratory and almost overwhelming,” Edwards recalls. The warehouse was filled with donations that, typical of many CSOs with money and staff constraints, were haphazardly stored, and the interns had to make sense of it. Still, though they identified several bottlenecks that reduced the flow of inventory through the warehouse, “it turned out that one of the best solutions was to do workplace organization [5S]” in a few areas,” he says.

Notably, the JPW Fund coaches use the same approach to guide the interns as they would use for any other professional, with few exceptions, allowing the situation to determine the specific lean thinking and practices the students would learn. One significant difference, of course, is the time allotted for the improvement effort, which forces the students to scope their work carefully. For example, Edwards recalls one team who “about a week or two before the midterm review, throttled back their expectations about what they were going to accomplish. So they knew they had their hands full and [some of their improvement ideas] might be another team’s project to carry across the finish line.”

Still, as they would when guiding professionals, the coaches allow the students to discover for themselves whether they need to rescope their plan: “We would ask them, ‘do you think this is attainable?’” Edwards explains. He adds that he sees scoping the work as part of the learning experience. “I think that’s part of connecting the dots, using appropriate tools, synthesizing things, etc.,” he says, noting that the coursework tends to focus on each practice or tool separately. With the JPW Fund internship, they’re pulling together the concepts to resolve a specific issue or achieve a particular goal.

Coaching to the Situation

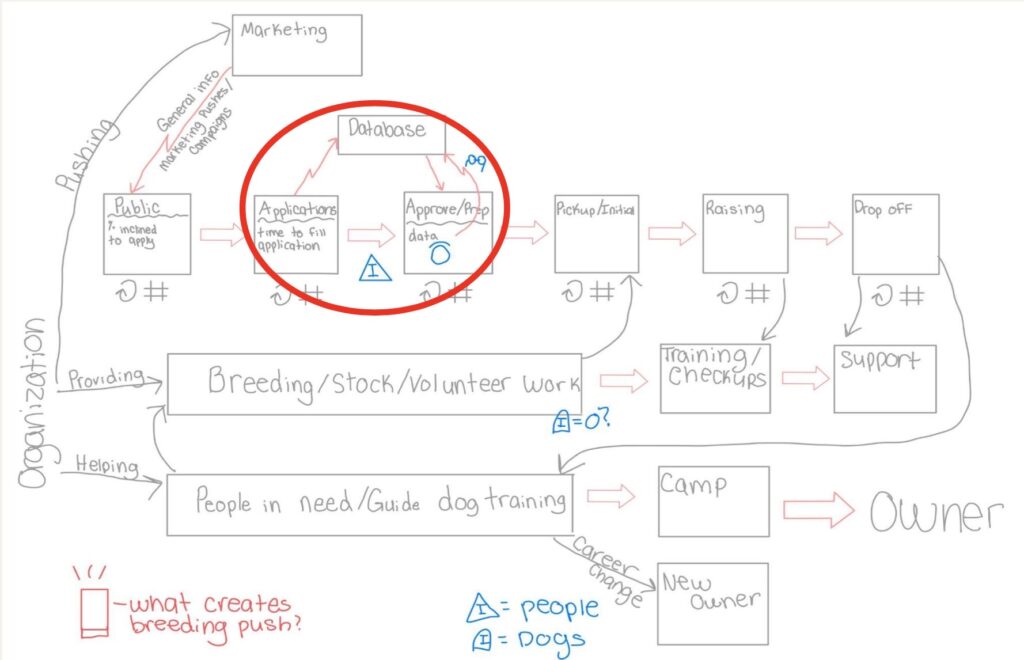

The first internship team at Leader Dogs for the Blind experienced an unusual situation requiring particularly flexible coaching and thinking. Instead of being allowed to analyze the situation and identify a problem to resolve, the CSO leadership assigned the interns to improve the online puppy-raiser application. Still, the coaches encouraged the students to use lean thinking and practices to understand and narrow down the problem, brainstorm and evaluate various ways they could resolve it, and define how it would make a difference to the organization. “Lean, in general, focuses a lot on defining the problem,” Shore explains. “But when you’re given a project, it’s still important to understand the problem.”

The coaches encouraged the interns to complete a value-stream map to gain a broader context to make their recommendations. “Even though there was a decision as to where to focus, we had the conversation about how you might map this value stream,” Ethington says. “Because the act of doing a value-stream map has value. In addition to getting a clear “picture” of it for identifying bottlenecks and other issues. You [also] do a value stream map so that the different stakeholders you’re talking to — you can have a better conversation with and get some alignment on ‘why are we looking at this one spot? Why is it important to the overall flow?’ So let’s look at the whole value stream, and let’s have a conversation about why are we focused here — [the reason] is something beyond ‘because the leadership told us to.’”

So, as part of their analysis, the interns completed an end-to-end value-stream map, which starts when a potential puppy raiser fills out an online application and ends when a puppy goes to its new home to help its new owner. “We did a general value-stream map to get a better idea of the organization as a whole and how different areas relate to each other,” Shore explains, adding that the map would also be available and helpful for future interns at the CSO. Kallen adds that the value stream map gave the interns “a bird’s-eye view of Leader Dog,” which helped them understand how each stage of the value stream feeds into and is fed by others. She says the map also helped them “stay in their lane.” They had identified other areas of improvement they would have liked to work on, but knowing the application’s crucial role in the value stream contributed to the overall mission — increasing applicants and application completion rates — kept them focused.

Adapting Lean Thinking to CSO Processes

Mapping the value stream at Leader Dogs for the Blind was tricky. Since it was not a traditional manufacturing value stream, the interns first had to think through what “product” was flowing through it and what processes added value to the product. This situation, Ethington explains, would be challenging even for someone with experience mapping a manufacturing facility.

With the coaches’ encouragement, Kallen and Shore also followed the A3 thinking process to understand their assigned problem. “We did do some work on that left side [of the A3 document] to support the project they had given us,” explains Kallen, adding that it was important to her to know how the work she was doing would help the organization fulfill its mission. To justify the problem, Kallen says, “We talked to the people who reviewed the applications to see what they need and what they were looking at and what their process was. Then we got input from people who had filled out the applications, the puppy raisers, and then we were given all of the data of every application from the last four years.”

Shore adds that the A3 thinking “definitely helped with understanding and then solving it,” he says, adding that it clarified “this is why we’re doing this, and this is the kind of impact we’ll see,” once they make the changes and determine how they would work to resolve it.

With the justification clear, the interns started researching how to make the online application more concise and easier to complete so that more applicants would finish the application and get a favorable first impression of the organization. Ultimately, they reasoned, these outcomes would yield more puppy raisers and, in turn, more puppies ready to be trained as service dogs and, therefore, more clients helped. They also noted that a streamlined application would save time for Leader Dog staff because it would reduce the time they spend reviewing completed applications.

“They have all these dogs and all these people that need these dogs. So it was good to see how all those [parts of the value stream] intertwined,” says Kallen, adding: “It almost seems silly that an application being miswritten or not formatted correctly would be the reason these people wouldn’t get a leader dog.”

With the decision on what to improve, lean thinking calls for the students to go to the gemba to see and experience the process firsthand. But they had no physical place to visit. So, instead, says Eric, “We encouraged them to treat it [computer screen] as their gemba.”

So, the students personally filled out the application, and each watched another person completing it, noting where they seemed to have difficulty. They also surveyed puppy raisers who had completed the survey to understand their thoughts about how it could be improved and interviewed the volunteer engagement and puppy raiser department staffers to gauge the relative importance of each question on the application.

Notably, as the interns reviewed the application, they viewed it as a process map. Among other things, they evaluated whether the flow of topics made sense, eliminated unnecessary questions, grouped others, and indicated the “branching questions” — those that applicants could skip when they didn’t apply to their situation.

With this specific information guiding their work, they reduced the number of questions from 77 to 47, including 17 branched questions, and the estimated time to complete from 30 to 18 minutes.

Coaching, not Directing

Overall, the interns agree that the JPW internship design and their coaches’ approach were structured yet gave them the encouragement and authority to drive their improvement efforts. By design, the structure ensures accountability while allowing the employee to experiment to learn while improving a work process — which most lean practitioners would consider an ideal supervisor-employee relationship.

Shore particularly appreciated the cadenced coaching check-ins. “Having the weekly meetings with our mentors was nice to keep us on track,” he says. At one of his other internships, he says he had fewer check-ins, giving him more independence. However, “If I had a project I wanted to get done tomorrow but couldn’t get it done, I didn’t have a meeting to talk to anybody about it, so I had to hold myself accountable. He adds that having two interns working together created a situation where they held each other accountable.

The type of guidance was also a plus for Shore. “Having more mentorship in this internship was nice,” he says, recalling that the coaches’ approach leaned more toward having the interns “do the critical thinking for ourselves rather than have them [the coaches] do it.” Instead, he says the coaches asked: “What do you think is the next step here? What do you guys think should be done?”

Kallen also appreciated the weekly cadenced meetings with the coaches and their availability. “If I ever got confused or stuck throughout the week, they would usually jump on a call with me,” she says, recalling that she’d reached out to Ethington to clear up her confusion about value-stream mapping and A3 thinking. “[Ethington] explained [value-stream mapping] to me in our weekly meeting, and then the next weekly meeting we went over it again,” she recalls. “Then he met with me one-on-one, [using] PowerPoint, and talked me through it and how it would be beneficial.” He similarly tutored her to “get her up to speed” about the A3 process.

Overall, for Kallen, the JPW Fund internships at “both Humble Design and Leader Dog were way more structured and coached than my other internships. I felt like I wasn’t ever alone in my decisions. With my other internships, it wasn’t like I didn’t have any support, but [they weren’t] as structured.”

Focusing on Leading Change

One realization that the coaches and interns note upon reflection: the JPW Fund learning emphasizes lean management to a greater degree than they initially thought it would. “These are student-led projects,” Edwards emphasizes. “These internships are not where the advisor or coach is going to take the reins and drive the project.” Instead, he adds that just as lean supervisors would with a junior engineer, the coaches drive results by asking Socratic questions and helping interns evaluate — again through questioning — what they think is going to be the best path. In contrast with the traditional “I’ll tell you what to do” management style, “the students tell us, then we ask ‘what other ideas have you considered? Can you walk me through your thinking on that?’” Edwards explains. “Hopefully, we give them confidence in their decisions by serving as sounding boards.” This approach enables the interns to enhance their skills while significantly improving the work process.

Zayko muses that the JPW interns’ work is much like a lean consultant’s because the students are working with — and even becoming coaches for — people who have little or no experience using lean thinking and practices. “I obviously interacted with the Humble Design team, but I tried to spend most of my efforts with the interns,” Zayko explains. “That was their opportunity to grow and make low-cost, low-risk mistakes, and that’s the best way to learn.”

He adds: “You’re, coaching interns who are not employees — and they’re students. So that was unique in [that] they are an extension of Humble Design. So, you’re trying to mentor and influence them, and then they, in turn, have to do the same thing for the people at Humble Design. “They were essentially consultants.”

The interns’ situation is “probably even a little tougher than if they were an inside person doing the work, because they’re kind of third-party help for the organization,” Ethington says. “We’re having to do some coaching about how to get people engaged – you’re almost coaching them to be coaches themselves, to a degree.”

The interns agree with those characterizations. Comparing her JPW Fund internship experience with her other four internships, Woolford notes, “In my other internships, my manager was the one who had all the connections with the company, so I’d go through them to get those connections,” she explains. “But in this role, we were the ones who had the direct connections.”

She adds: “I would say for the JPW, it seemed like it was more our project, and we would go to our mentors for occasional help. [In my] other internships, it felt like it was the manager’s project that I’m just helping out.”

Kallen agrees, recalling that during her and Woolford’s Humble Design internship, for example, “after that initial meeting, there wasn’t [much] communication between Humble Design [staff] and our mentors, I don’t think.” Also, she adds, “we pretty much ran the mentor meetings; we would just come with questions and what we wanted to do. Sometimes Lauren and I would be on the phone with them [the coaches] for like five minutes for our weekly meeting, because we didn’t really need any help. We had it under control. So yeah, they were our consultant, and we were their consultant.”

Woolford recalls a similar experience: “We pretty much ran the mentor meetings; we would just come with questions and what we wanted to do,” she says. She noted that, compared to her other internships, where she had a manager “walking through everything with her, this one was “here’s your mentor that you’ll meet with once a week, but the rest will be you working.”

Developing Future Lean Leaders

Either way it’s characterized — whether a supervisor-junior engineer, consultant-client, or coach-learner relationship — the JPW Fund internships, to date, have provided students with hands-on experience in leading a lean transformation. Being 100% focused on lean learning, led by professional coaches, and putting students in a role where they’re introducing lean thinking and practice concepts to others and resolving real issues, the internship offers a learn-by-doing lean management experience.

With this internship, “we’re setting the students up for success in their professional careers — I think, [with] the tools and experiences, many of these students are going to be tomorrow’s leaders,” Edwards asserts. “One of the things I think it does is give them confidence, with this background, to speak up or be a bit more forward in voicing their thoughts or concerns, because of this hands-on experience,” he adds. “They can draw upon it and say, ‘when we were doing this at Humble Design, we found it effective to do this.’ It’s no longer theoretical.”

The students agree. “I just feel like it was a lot of learning, and I gained a lot out of it. It worked really well with my school schedule; it wasn’t overwhelming,” Kallen says. I really enjoyed it, and it helped me a lot.” She adds that her experience prompted her to write her honors college senior thesis on lean in nonprofits versus manufacturing.

Woolford concurs, noting that the 10-hour commitment was manageable as a student taking other classes while “still giving you experience, not a nine-to-five experience, but still pretty realistic experience.”

Shore liked having the opportunity to see how lean thinking and practices work in a non-manufacturing-oriented, noting that seeing how lean applies to improving the online application “gave me some good experience with working on that sort of [project]. And I think that will definitely help with future projects that I do.”

Managing to Learn with the A3 Process

Learn how to solve problems and develop problem solvers.