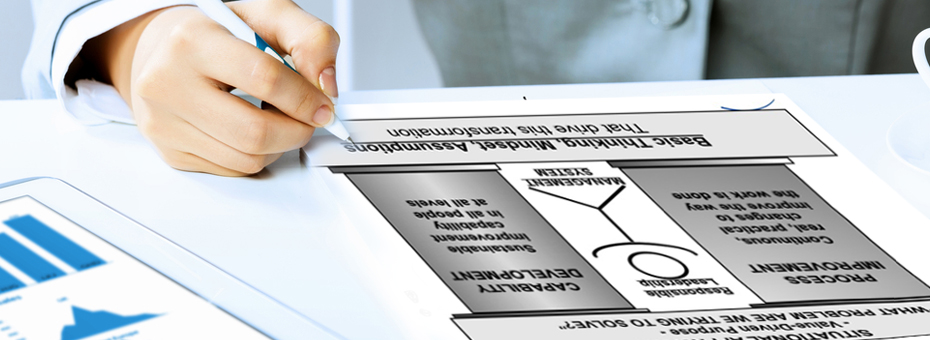

The five dimensional Lean Transformation Model, developed by the Lean Global Network, is something we have taken up for validation at the Lean Management Institute of India (LMII). We first deployed it in manufacturing where many mature interventions for quality improvements either have not been successful or could not be sustained after limited initial success.

LMII approached a major auto OEM supplier (let’s call them company X) that was keen to improve the quality of their suppliers. LMII requested company X to identify the worst set of their suppliers: suppliers that had chronic quality problems whose performance could not be improved beyond a certain level (despite repetitive attempts). The purpose, the “business problem to be solved,” was finalized as PPM (part per million) levels. Goals and targets were set: “Reduce PPM by 50% in 4 months.” We also put to test our own LMII engagement principle for working with companies: “The value of what we deliver will be measured by what happens after we go away.” We would pay attention to sustainability of any gains achieved and watch the problem solving and improvement capabilities levels of those individuals responsible for driving change, including setting new goals and targets.

First, we did a gemba walk with company X and a few of their suppliers to develop an effective team of individuals who would manage the technical as well as social aspect of company X’s transformation. We focused on coaching and made all aspects of project management visual.

When it came to helping company X improve the actual work, we suggested a two pronged approach:

- analysis of past data through multi-level pareto to understand generic and repetitive defects from the customer’s point of view. After focusing in on one problem, using root cause analysis, the team identified the point of cause quickly. Visiting the gemba at the point of cause helped the team see defects occurring right in front of them. This aligned the team, root cause was agreed upon quickly, and soon team members began brainstorming many potential countermeasures.

- developing an understanding of their current defects and daily problems from the customer’s point of view.

Once company X determined these things, they communicated this information to the plant through samples or photographs of defect products. In the evenings, company X met in an Obeya room to do root cause analysis. Over time, everyone became sensitized to problems and defects from the view of the customer. Company X decided they would take a “customer first” approach, stopping errors wherever they occurred.

While these activities improved business at company X, this team was just getting started. As they worked on future improvement activities, they recorded their progress, identified new areas for improvement, assigned ownership for all activities, and tracked each experiment’s results. They carefully studied PPM trends.

Just one month after project kickoff, company X’s head of Supplier Quality said, “I do not know if this project will meet its objective, but one thing I can say for sure: Now, in our top management review meetings, we no longer [talk] about suppliers.” This had always been the case before. He continued, “During management reviews we were always on the firing line [because] of supplier quality issues. We had to look for cover.”

After two months, company X’s suppliers were receiving nearly 150 pieces of new information/errors to review and improve. Once company X’s leadership team began to scratch the surface and actively problem solve, new errors revealed themselves.

At one supplier, particular defects kept repeating.

Another supplier’s sub-supplier changed abruptly, creating instability across the extended supply chain. While this new sub supplier was technically sophisticated, it was also a competitor. As a result, at this suppliers at least, the improvement failed miserably.

Still, for company X, this was all part of process improvement and capability development for problem solving through “grasping the situation” and frequent PDCA. This failure with one supplier was only one part of a large number of improvement activities.

Company X analyzed all improvement project points using a K-J Diagram, also known as affinity mapping. Company X used this information to form a spin-off improvement team, focusing on what they called systemic issues. (This was a great learning for something that had just gotten started 2-3 months prior). This new team designed new processes based on company X’s learnings working with suppliers and again worked to implement changes. This time, three key suppliers exceeded their goals and targets. They even set more challenging goals and targets and continued on.

Two other suppliers, whose management did not follow company X’s new processes or adopt lean principles ended up in worse situations. Their PPM levels increased or remained the same. But after several conversations, both suppliers’ management teams came to understand their mistakes. Once they started working on the inputs provided to them earlier and some later, both suppliers eventually achieved fantastic results.

So, what did we find out about the Lean Transformation Model?

The Lean Transformation Model works. It works in situations where many attempts at TQM did not work (TPM and Six Sigma in our experience had actually failed to make any difference at all). We’ve also found this five dimensional transformation model to be effective when leaders act as coaches and to be ineffective when leaders do not. We were even able to convert LMII’s “failure” cases into success stories after their leaders began acting like coaches with their teams. We can say with confidence that coaching by senior leaders is core to success of any lean transformation.

The real success of the Lean Transformation Model has been proved beyond a shadow of a doubt by the fact that company X has now selected a new set of 10 suppliers and engaged with us again to reduce their PPM by 50% in 4 months time. The earlier set of suppliers presented their cases to the new set of suppliers at the kick off meeting. This event took place after four months after the closing meeting with earlier set of suppliers. This was remarkable as it proved our engagement principle: “The value of what we do is what happens after we go away.”

Our challenge now is to prove the consistency of the Lean Transformation Model so we can help companies deliver results again and again. This also gives us an opportunity at LMII to prevent potential project failures the first time, or at least catch problems sooner. We look forward to trying out this transformation model in manufacturing and non-manufacturing organizations, working on a wide variety of business problems and getting it right the first time.