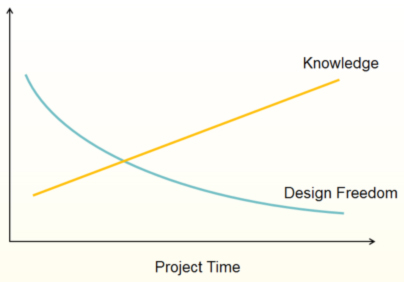

If you have ever worked on a design project or any other open-ended, ill-defined problem, you’re familiar with the designer’s dilemma.

It works like this: at the beginning of a project you have a lot of freedom to take the design or project in many, possibly infinite, directions. But you also don’t know that much about the problem or the potential solutions, so making decisions during those early phases of the project is challenging because your level of knowledge is low.

Fast forward to the end (or near-end) of the project: your knowledge about the problem and the solution is at its best. But unfortunately, because of the decisions and commitments made throughout the whole process leading up to that point, you’re now more constrained than at any previous time in the project, so you have the least amount of freedom to act on that knowledge.

That’s the designer’s dilemma—you have the most freedom to make decisions when you know the least about the problem. But as you learn more, you become increasingly constrained in your decision-making and ability to change course.

That’s the designer’s dilemma—you have the most freedom to make decisions when you know the least about the problem. But as you learn more, you become increasingly constrained in your decision-making and ability to change course.

If you’ve ever said, “If I had known then what I know now, I sure would have done things differently,” then you have experienced it.

Why does the designer’s dilemma exist? Part of the reason is that solving design problems (and similar problems that are open-ended and ill-defined) requires, to a significant extent, a discovery process. We have a lot of learning to do in order to understand all the ins and outs of problem, its social and environmental context, interfaces, technical possibilities, and the like. So necessarily we have to grow our knowledge in order to solve the problem. And because we do not have infinite capacity or time in which to solve the problem, we have to pick and choose where to focus our discovery efforts. In other words, we make decisions that take us in a certain direction. Those decisions lead to other decisions and so forth… and next thing we know, we’ve invested a lot in a given solution path, making it difficult to change course.

Another part of the reason, especially in engineering contexts, is the approach often used for design problems. Typically, after considering a number of potential solutions, the team selects the one that seems best at the time. They then add detail to that idea, analyze it, and refine it until it meets design requirements. The difficulty here is that we don’t know when or if such a process will arrive at an acceptable solution. This does little to resolve the designer’s dilemma. And the effects are made worse in an organization context, which is where a lot of product development happens. Changes by one person lead to changes by an interfacing subteam which leads to changes by a third person or team, and so forth in a domino effect that may never come to an end. Some call this phenomenon design churn because of the turbulence it creates within the organization.

Fortunately, there is something we can do about it! We can mitigate to a significant extent the deleterious effects of the designer’s dilemma by applying the practices of set-based innovation. One practice in particular is especially useful for combatting the designer’s dilemma: trade-off curves.

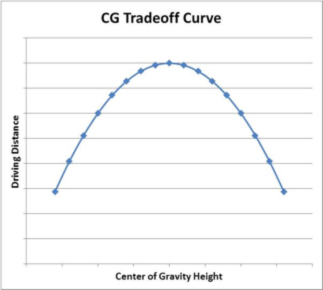

Using trade-off curves, we try to understand the design problem in a more general sense, based on the underlying principles that govern the situation. For a given design concept, how are the performance metrics that the customer cares about affected by changes in the values of design decision variables? This relationship can be displayed graphically for quick and easy communication, and for fundamental understanding.

Using trade-off curves, we try to understand the design problem in a more general sense, based on the underlying principles that govern the situation. For a given design concept, how are the performance metrics that the customer cares about affected by changes in the values of design decision variables? This relationship can be displayed graphically for quick and easy communication, and for fundamental understanding.

For example, a golf club manufacturer knew that the center of gravity of the golf club head has a significant effect on how far the ball will go when hit. Too high or too low from the ground, the ball will not travel in an optimal arc to produce maximum distance. By running a series of experiments using an easily modifiable golf head, the development team generated trade-off curves which show exactly where the optimal center of gravity is, and how sensitive travel distance is to deviations from optimal. This is knowledge gained about general golf club design (as opposed to a specific golf club head design) without reducing design freedom since no decisions have been made. As the team accumulates such in-depth knowledge, the design problem comes increasingly demystified. At some point the team would simply need to select where they want to be on each of the curves, draw up the detailed design, and release it.

Dr. Allen Ward (author of Lean Product and Process Development) claims that trade-off curves are the most powerful tool in the lean product-process developer’s tool kit. Do you agree? What experiences have you had with trade-off curves? What advice do you have for people starting to learn about them? Let us know what you think.