For as long as I’ve been in contact with Toyota I’ve heard its executives worry about “Big Company Disease.” What is Big Company Disease? The tendency any large company has to worry about clearly defined territories, rules and procedures, and integrated systems more than a passion for quality or the kaizen spirit.

The aim of a start-up is scale-up. Without ambition to scale up, a start-up remains a pop-and-mom shop. And Big Company Disease unavoidably accompanies scale-up, as we see by reading in the press about all the growing pains of even the most promising start-ups.

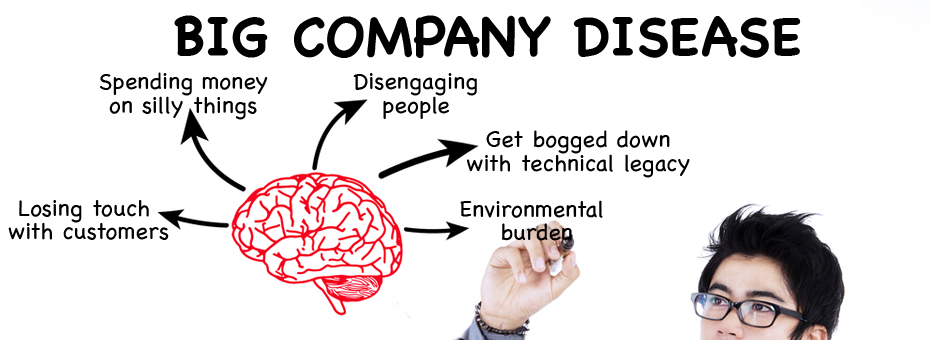

The five poisons of Big Company Disease are:

- Losing touch with customers: A company scales up because customers like it, like its products and services and trust that they will continue to like it. But as the company grows it loses interest in its existing customers and seeks new markets. Or it adds features no one really cares about. Or it is swamped with demand and stops delivering. Or… you just don’t like the new logo. For a multitude of reason any growing company risks getting so focused on 1) acquiring new customers and 2) setting up systems to sustain growth that it’s easy to lose touch with the very customers that are a foundation to sustainable growth.

- Disengaging people: At first, working with a start-up is demanding but fun. Then, as it becomes successful, ambitious managers see there is a potential career move and join the fun to run it better (make room for the adults they say). And they kill all the fun. Sure, any business needs some degree of predictability, with plans, budgets, rules, silos, systems, and so on – all meant to bring greater “clarity” and to avoid duplication of effort or confusion. But the upshot of such management efforts are usually to lose sight of employees and actively disengage them by turning them into slaves to the system. Follow what your computer says. Ask HR for permission. Make the boss look good – all the things everyone hates but accepts as part of life in any government office (oh, sorry, growing company).

- Spending money on silly things: Wasting time with meetings is the least worse way of spending money on useless things. The moment the cash starts rolling, watch management invest in the new warehouse (we need to hold all this inventory to deliver to our customers); the new headquarters (we need to impress our clients and attract talent); the new machine (German engineers swear by it); the new improvement program (well, we need to pay for all the previous expenses) – rather than, say, raise employees’ wages or reduce prices for customers.

- Get bogged down with technical legacy: Hire a kid out of university, take any function of your product or service, and ask her to put it together with the technology lego bricks she grew up with – you’ll be amazed. What will be less surprising is the chorus of middle-aged rebuttals and explanation of why this new tech can’t possibly work with our platform or, worse, if it did it would put us all out of business. It’s easy to become an old start-up very quickly (one that didn’t really catch on to the scale-up thing), and it’s amazing to see how quickly yesterday’s newer clever tech becomes today’s legacy problem.

- Environmental burden: To be fair, the start-up probably had the same environmental burden but nobody cared much. It was a start-up! But now that it’s all grown up, what used to be counted in cents now adds up to thousands, and so does the environmental footprint (or simply the impact on the neighborhood). These kids used to be fun and innovative, but now it’s all fat cats and SUVs. What can you do?

This is what Lean is really about – scale-up while actively fighting big company disease. Toyota grew from producing 1 million cars in 1965 to 4 million in 1990 to 8 million in 2008, when Lehman Brothers collapsed, taking much of our economies down with it. It made 10 million vehicles last year. That’s scale-up.

According to Professor Hirotaka Takeuchi, Toyota sees itself as a green tomato, never a red one. Toyota knows it suffers from Big Company Disease. This is the problem Lean was invented to solve. In Kiichiro Toyoda’s terms, seeking “the ideal conditions for making things are created when machines, facilities, and people work together to add value without generating any waste.” To understand Lean, you first have to understand the five deadly poisons of Big Company Disease.