Editor’s Note: This Lean Post is an updated version of an article published on May 20, 2014. It is the second in a three-part series focused on the importance of people development in creating and sustaining a lean enterprise. The series explores the theme through three critical dimensions: leadership, coaching, and training. This piece delves into training. Read the first part in the series here.

A consistent critique of lean in the U.S. is its overarching emphasis on processes, techniques, and tools at the expense of, or even ignoring, the most critical aspect of all, the importance of people in making it all work – what Toyota likes to refer to as Respect for People.

Running an organization that truly respects its people and works on company culture first, before trying to implement tools that work on the production system, is a lesson that most organizations miss. Without the enthusiastic participation of people, in particular those people who actually do the work, we will not get the “buy-in” necessary to see that needed changes actually take place and are sustained.

Lean practitioners will tell you that the philosophy of engaging people directly in how they do their work came to us from Japan when interest in Japanese management took off in the early 1980s. At the time, the notion of asking operators their ideas and opinions was quite revolutionary. My colleague, Bob Wrona, tells of how as a young supervisor at GM in the 1970s he was disciplined for talking with the workers and being “too friendly.” The funny thing is that when I got to Japan in late 1980, the Japanese managers I met were dumbfounded at all the attention being given to their management practices. “Why is that?” they asked, “You taught us everything we know.”

In their groundbreaking research reintroducing TWI into the American arena, Alan G. Robinson and Dean M. Schroeder, in an interview from August 1951, reported that the “concept of humanism in industry” was “one of the most appreciated ideas transmitted into Japan by TWI.” (Training, Continuous Improvement, and Human Relations, California Management Review, Winter 1993.) The notion that good management included a respect for individuals was not, at that time in history at least, a part of the Japanese style. Robinson and Schroeder claim that, in addition to developing an appreciation for a more rational approach to management, TWI was able to teach the Japanese that “good human relations are good business practice, a message that is given credit for helping break up the tradition of autocratic management prevalent in Japan before and during the war.

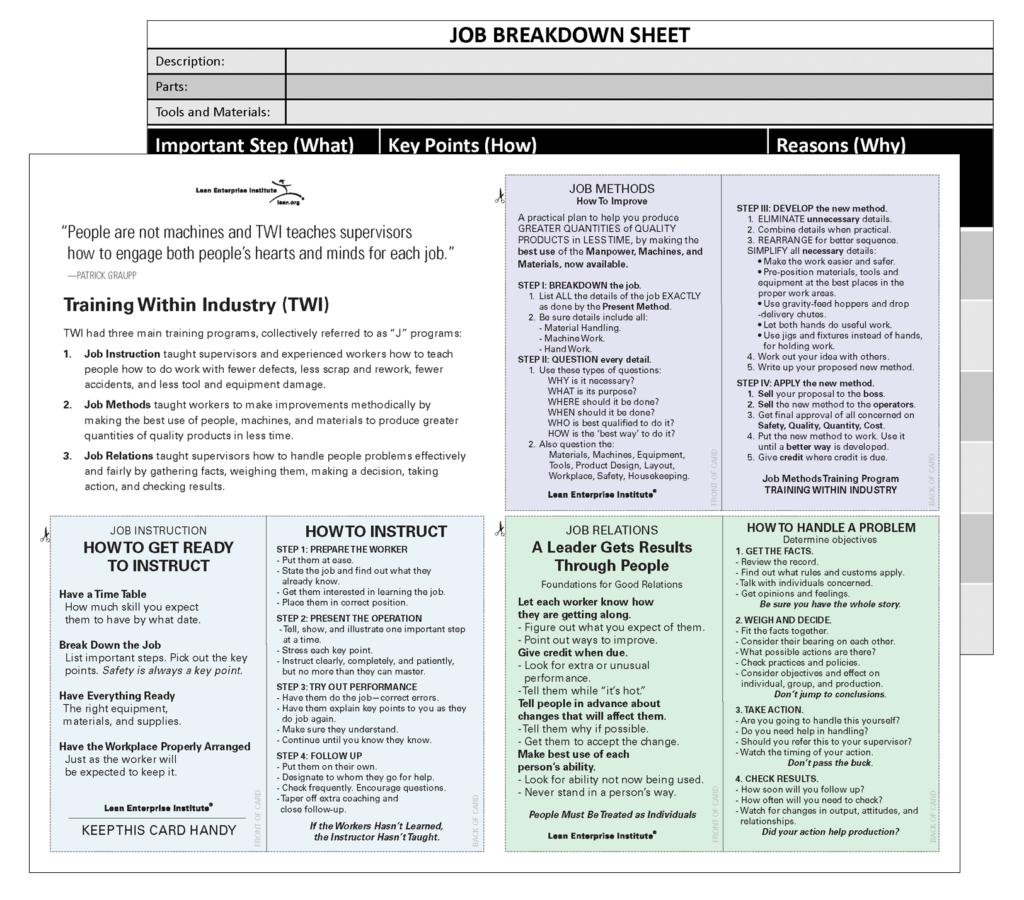

Whenever I teach the first session of the Job Methods module of TWI, in the demonstration example of Assembly of the Microwave Shield, I point out how the supervisor worked with the operator to include his ideas for improvement as well as her own. I mention that this is exactly, minus the gender changes, how the demonstration was presented in the 1940s when the program was first taught. The dialogue in the training manual actually has the trainer say, “Operators have good ideas, too; often just as many as we have – sometimes more!” In other words, this is an approach which we as Americans have always known works well, but lost somewhere along the way. “It’s the American Way,” I tell them with as much bravado as I can muster, “born right here in the good ol’ U.S. of A.” (It doesn’t really matter that it was Made in the U.S.A. – I just say that to tap into their pride in order to encourage them to use the method). In fact, all of the TWI methods contain this spirit of respect when it comes to dealing with frontline people.

When I’ve taught the TWI courses in countries all over the world, from India to Malaysia to Mexico to Germany, everyone understands and embraces these concepts because the focus on humanity is universal. These concepts transcend culture and economic barriers.

Unfortunately, though, most front line supervisors and managers I meet today still resist or reject anything they consider “touchy-feely”. For them, this is something that may sound good but, in the end, does not produce results. They may not have faith in the sincerity and work ethic of their people or, more likely, they just may not have the skills to lead their people in a way that would be truly motivating. The underlying values of all the TWI programs, indeed what the Japanese found so appealing when they were first introduced to TWI, encompass these leadership qualities.

So, what are the human elements of TWI? And why, if applied, do they lead to the ultimate success of the methods? Oftentimes in a Job Instruction session when I introduce the core concept of “If the worker hasn’t learned, the instructor hasn’t taught,” a skeptical participant will speak up and say, “Now wait just a minute! You can’t put that on me. If you only knew the kind of people I have to supervise.” When I challenge them on this they almost always fall back to the position: “Even if I had a good instruction method, they still wouldn’t listen to me.”

Download the Free TWI Reference Guide

This may be true. But when this happens, it isn’t a problem of instruction, it’s a problem of leadership. The Job Relations module of TWI defines a leader as a person who has followers. If people are not following your instructions, you are not leading them. The goal of good Job Relations is to gain the dedication and cooperation of people in getting the work done. When we apply the JOB RELATIONS method of developing and maintaining good relations with people, only then, when people want to do their jobs correctly, can we expect good results from our instruction effort.

Moreover, Step 1 of the Job Instruction method, Prepare the Worker, is dedicated completely to putting the learner in the proper frame of mind to learn. By calming their anxiety over doing something new and letting them know why the job is important, supervisors can get the learner interested in the job and to care about learning to do it right. By finding out what they already know about the job, even from a skill in a hobby, we put it into a context that fits their life. Then, in Step 2, Present the Operation, by telling them the reasons for the Key Points to the job, we pay respect to their mental ability to understand the significance of the job details so they can do them conscientiously. It takes considerable practice to use this skill properly because supervisors are not accustomed to paying attention to the human element of learning, in addition to all the technical aspects to the work.

People are not machines and TWI teaches supervisors how to engage both people’s hearts and minds for each job, no matter how simple or small.

TWI skills are aimed at helping supervisors get quality work done on time and at a competitive cost by recognizing and engaging the vital element of people in this equation. “As proof of that,” the Job Relations manual preaches, “Try sending all of your people home. How much work will you be able to accomplish then?”

Investing in Work(ers) Using Job Methods and Job Instruction

Learn how to develop team members for sustained success.

I find this article very instructive on the crucial role of people in the success of Lean methods. I agree with you that without the enthusiastic commitment of frontline people, it is difficult to implement effective change. I appreciated the mention of TWI methods and their impact on corporate culture, especially in the Japanese context. How do you think companies can overcome the resistance of managers to the “touchy-feely” aspects of Lean Management?

Good day

Thank you for the article.