There have been countless articles and books written about leadership in a company that is transitioning from a traditional strategy to a Lean strategy. A common theme is that leaders have to change their behavior from “traditional” to “lean” behaviors (which in many cases are 180 degrees opposite of what they currently do). I agree with this and when I teach a workshop I discuss how there must be a personal transformation before there can be an organizational transformation. I also present, and discuss, a list of Lean leadership behaviors.

However, I get the sense that there is an underlying assumption (wish?) that someone will wave a magic wand so that the senior leaders will “get it”, adopt these lean behaviors overnight and happily lead the lean transition, overcoming any resistance from the lower levels of the organization. In my experience, the reality is that when confronted with this type of fundamental personal change, most leaders will give it an honest try, but because of how difficult it is to overcome long-term habits (ever tried to quit smoking?) they quickly revert to those behaviors that have worked for them in the past. That was certainly a challenge for our senior leadership team at The Wiremold Company when we accomplished that personal transformation.

In 1978 I left public accounting and joined The Wiremold Company (a family owned company founded in 1900) as CFO. The company made products in a niche called “wire management” and was the market leader in most of its product categories. Between 1978 and 1987 sales and profits grew every year. One of the contributing factors was that we had no foreign competition. We could, however, see that this was going to change as some foreign companies were gearing up to enter our markets. We assumed they would sell lower cost products, thereby putting price pressure on our products. Although the quality out the door to our customers was high, that was the result of strenuous inspection and a lot of internal scrap. We were far from being a low-cost producer and recognized that we had to get better.

In 1988 three things happened that affected my thinking.

- We acquired a company that was heavily committed to the thinking of Dr. Edwards Deming; and I attended Dr. Deming’s four-day seminar.

- I saw the NBC program entitled “If Japan Can, Why Can’t We?”

- I read Relevance Lost: The Rise and Fall of Management Accounting by Tom Johnson and Bob Kaplan.

Listening to Dr. Deming for four days was an experience that defies description. One of the many takeaways was Deming’s 14 Points. His discussion of these points convinced me that Wiremold had to adopt them as its operating philosophy. As a result, I convinced my fellow executives to attend Dr. Deming’s seminar.

The NBC broadcast about Japan’s business practices (remember, at that time it was believed that “Japan, Inc.” was going to “take over” the business world) showed a different way to think about how to operate a business…i.e. “Just In Time”. I also obtained a copy of the NBC program and showed it, first to the entire management team, and then to all of our employees.

Although Relevance Lost did not result in any immediate changes, it laid the groundwork for what would happen with our management accounting system over the next few years: the abandonment of Standard Cost Accounting and the development of alternatives which are now part of what is known as Lean Accounting.

In late 1988, Wiremold committed to a “Total Quality” program based on Deming’s teachings and Just-In-Time (JIT), based on the limited information we had about what Toyota was doing. In early 1989, our Vice President of Manufacturing retired and we hired as his replacement someone that claimed to have successfully implemented JIT. By the end of 1990 we discovered that we didn’t know what we were doing when it came to implementing JIT. We were so ignorant that we were implementing a new MRP system at the same time we were trying to implement JIT, not realizing that they were incompatible: MRP was a “push” scheduling system and JIT was a “pull” scheduling system.

Our new VP of Manufacturing, in order to reduce inventory, had started by changing the formulas in MRP to reduce safety stock levels and lot size calculations without improving anything in manufacturing. As a result, we were experiencing higher levels of out-of-stock instances and our on-time delivery performance to customers started to decline from its historical level of 98%. As our stock-outs became worse, we incurred lots of overtime trying to keep up and our cash was declining rapidly. The downward spiral continued and our on-time delivery rate went below 50%. As a result, customers were not paying us on time (tying up more cash) and we were losing market share to competitors. Our recently hired VP of Manufacturing left the company.

In December 1990, our CEO decided to take early retirement (although remaining on the Board for eight more years). He believed that Total Quality and JIT were the right thing to do, but realized that he did not have the knowledge to successfully lead their implementation. A search was performed to hire a new CEO, and Art Byrne, a former Group Executive of the Danaher Company, joined Wiremold in September 1991.

Art inherited a company whose sales had been flat for several years and whose earnings had declined by 80% over the past two years. He also inherited four executives that had varying backgrounds and number of years with the company, in addition to two unfilled positions. After these positions were filled the group’s backgrounds and years of service with the company looked like this:

- 5+ Years with Wiremold:

- VP Finance (Public Accounting)

- VP Sales & Marketing (Electronics)

- 1-5 Years with Wiremold:

- VP Human Resources (Banking)

- VP Engineering (Solar Energy)

- Added:

- VP Operations (Automotive)

- VP Marketing (Electrical)

Although in 1991 the word “lean” was not being used to describe what Toyota was doing, I will use that word in the interest of simplicity.

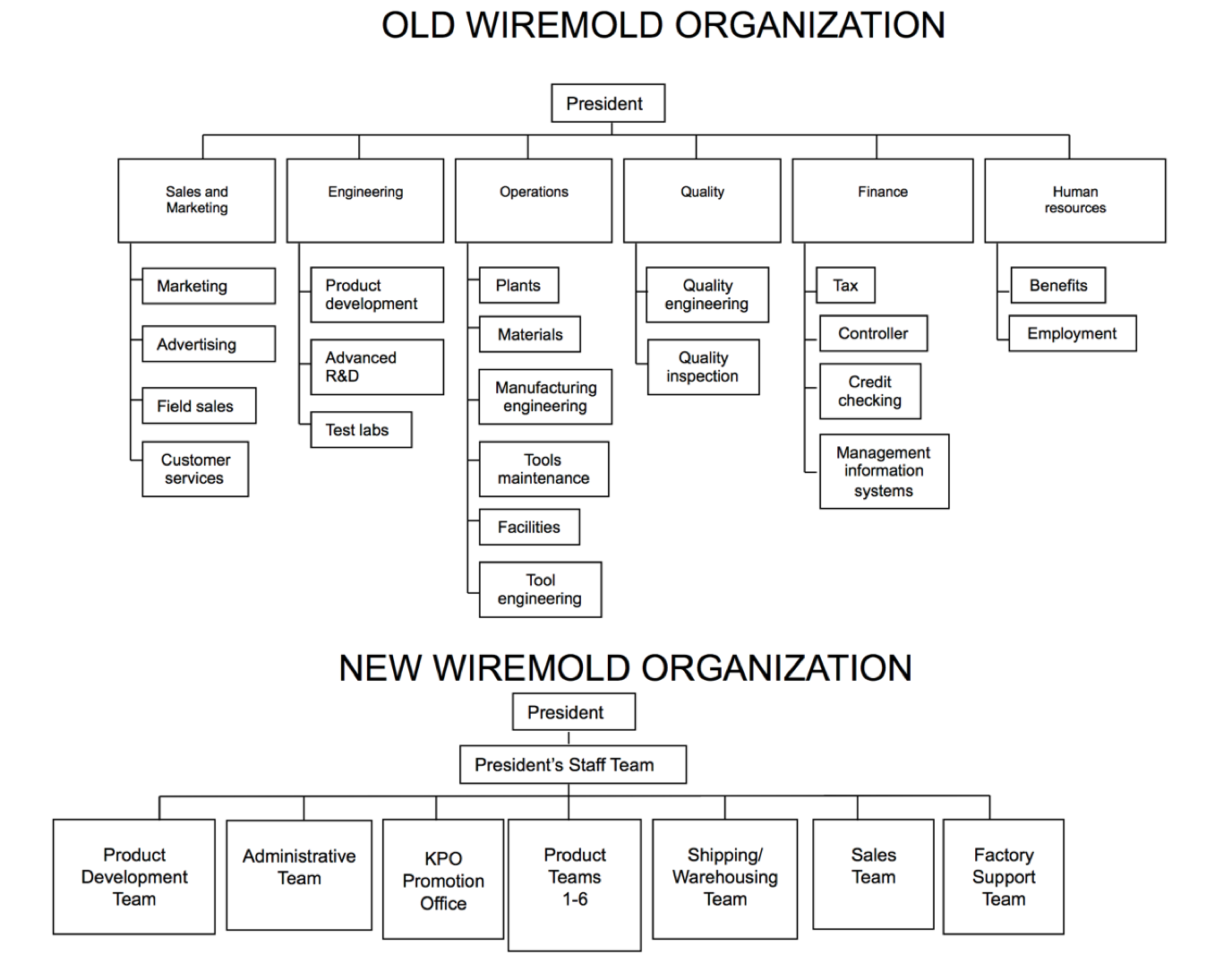

The first thing that Art taught us about lean was that it is a complete business strategy. Based on his experience at Danaher he realized that it was a superior way to compete. He also realized if we started to change things in manufacturing, but the other company functions continued “business as usual” there would be significant clashes. Thus everything we did and every policy that we had needed to support the lean strategy. Absolutely nothing would be exempt from being changed, if necessary. No “sacred cows”. This made sense to us and we began implementing our new strategy. This included a reorganization:

The “staff team”, which consisted of the vice presidents, was expected to act as a unified team. The twelve team leaders reported to us as a group. The reorganization also significantly changed our executive compensation program from individual incentives to a group incentive: we all earned our incentive compensation base on achieving certain goals…or none of us did.

By the end of 1992 we had improved results dramatically. Our gross profit improved by more than 2 percentage points, inventory turns improved from 3.4 to 8.5 and productivity increased by about 40%. As a senior leadership group we thought we were pretty good.

And then the bombshell.

During those early years Art met with his staff team to discuss the issues that were being uncovered and how to reallocate resources to deal with them. At the end of one of these meeting Art said, “By the way, if I have to be a referee between any two of you again, I will find people who can solve their issues without my intervention.” And then he left the room while we sat there speechless.

Obviously two of us had a disagreement about something, could not resolve it, and went to Art for him to decide. Although no one owned up to that, we all recognized that Art was serious. We all thought that we were acting as a team, but obviously he didn’t think so. So we continued the meeting on our own trying to determine how to deal with this problem. By the end of the meeting we decided to bring in an outside facilitator to help us.

The person we hired had been working with the company on something else so he knew the company and we felt comfortable with him. The first thing he did was to interview each of us alone to get our individual opinions about the issues within our team. He then arranged a series of three two-day meetings off-site spread over several months. Even though these meeting would be held at a local hotel, we could not attend them by commuting from our homes. We had to stay in the hotel for the two nights, with a roommate, and he would pick who would room with whom…after all, based on his previous interviews he knew where the interpersonal issues were.

Before we had the first session, Art somehow found out about what we were doing and said, “That sounds interesting. Can I attend also?” And as a group we said, “No! You said we have to figure out how to become a team, and we will do that.” Even today, I’m not sure that Art wasn’t concerned that he was creating a “monster”.

At the first session, we discussed “team theory”. There are several, but the one that seemed to fit what was happening to us was: Forming, Storming, Norming and Performing.

- Someone (in our case Art) formed a team…The Staff Team.

- Although we all publically subscribed to the lean strategy, each of us had reverted our personal agendas…resulting in below the surface storming.

- As a result of this process with the facilitator we wanted to agree to a set of rules of behavior (norming) that was consistent with being Lean Leaders…

- Hopefully, resulting in being able to perform at even higher levels.

When we recognized that we were still in the “storming” stage, our facilitator guided the conversation to more personal topics. I’m sure that our individual comfort levels with this varied greatly, mine being pretty low. After all, I’m an accountant who was comfortable with facts and figures…not feelings.

During the first session we talked about “prouds” and “sorries”:

- What makes me proud of this team is…

- What makes me sorry about this team is…

We talked about the “fruitful four”:

- Taboo topics in this team are…

- Some of the myths in this team are…

- In this team, conflict is…

- This team functions as if…

We identified the team’s strengths and weaknesses.

On the first morning of the second session we arrived to find a flip chart near each of our chairs. At the top of page one was the statement “Joe, you piss me off when…” At the top of page two, “Sam, you piss me off when…” The names used here are fictitious, but we each had to fill the pages for every one of our other team members. The ensuing discussion consumed the rest of that day and all of the next. The interesting part about that exercise was that there were very few deep-seated issues. Most of the things were pretty superficial but created repeated annoyances.

In the third session we talked about:

- A team is…

- We would be a better team if…

- We would have better teamwork if…

This resulted in an agreed set of norms of how we would act as a team. We also discovered that we liked and trusted each other. We could have honest differences of opinion on issues and would work together on solving those issues, but when we finished those discussions we still liked and trusted each other. In addition, it’s not uncommon in a traditional environment, when a decision is made, some people in some functions will try to undermine it by convincing their boss that it didn’t “benefit” their function. As a result of these sessions, when people that tried to play us against each other, or just expected the status quo, they were shocked how united we were on decisions. That was particularly visible between the sales, marketing and engineering teams, which in many traditional companies have long, antagonistic histories.

As to the “performing” part…that’s been recorded in a number of places including two books that I have co-authored: Real Numbers: Management Accounting in a Lean Organization and The Lean Strategy. By the year 2000, when we sold the company, sales increased more that 400%, gross profit improved by 13 percentage points, inventory turns increased to 18 and the value of the company went from $30 million in 1990 to $770 million in 2000…an increase of about 35% per year. There is no doubt in my mind that we achieved these extraordinary results because of Art’s leadership and our staff team’s new found ability to be Lean leaders.

One of the other things that came out of our transformation into a highly functional lean leadership team was a code of conduct for ourselves and everyone else in the company:

- Respect Others

- Tell The Truth

- Be Fair

- Try New Ideas

- Ask Why

- Keep Your Promises

- Do Your Share

A final observation: at some point a new person was added to the staff team and it didn’t take long for us to notice that the team was not acting as smoothly as it had been. As we discussed the reasons for this we realized that we were back in the “storming” stage. Anytime a new person joins any team, that team is automatically back to the “forming” stage and, logically, moves on to the “storming” stage. Fortunately we recognized that quickly and were able to move onto the “norming” and “performing” stages without the assistance of a facilitator.

I began this article with the statement that there is an underlying assumption that senior leaders will just “get it”. I have never seen a company where this is true…including Wiremold. We didn’t automatically change our behaviors just because Art expected us to. As I look back on that experience it took what now seems to been akin to group therapy to achieve it. As I mentioned earlier, there has been a lot written about the attributes of a good lean leader. However, I haven’t seen an answer to the question “how do you get from here to there?” with “here” being a group of traditionally educated executives with traditional experience of being promoted based on their individual expertise and performance. That’s what we were and we all carried a lot of baggage based on our individual histories.

But, as Art understood from his days at Danaher, you can’t make the transition to lean unless the management team acts as one. Our new structure of the12 teams reporting to the senior management team (as a single entity) reinforced this. We couldn’t afford to have our associates getting different answers depending on which vice president they asked. We also couldn’t afford to have any one function going in its own direction. Our customers just saw us as one entity, The Wiremold Company. Any behavior that didn’t conform to this was just waste. So I don’t tell this story as a recommendation that every company’s leadership enter into group therapy. I tell it so that this issue is out in the open and each leadership team can find its own path to discarding its baggage and become successful lean leaders.