If they haven’t trained themselves to do so, even the most brilliant people can make absurdly wrong decisions because they lack “frame control”. In the early days of the epidemic, experts in epidemiology underestimated the scope of the problem by at least a factor of 10, sometimes 100-fold. Governments around the world shut down their entire countries to protect intensive care units in hospitals. As the dust clears, we will realize that in the heat of the moment, in some countries, we forgot everything we knew about epidemics, such as spotting outbreaks early through testing, isolating contagion hotbeds, and improving sanitation.

A frame is the mental equivalent of a picture frame – the rectangle through which you look at the situation. If you’re only seeing overflowing intensive care units, it makes sense to lock down the country. If you have some frame awareness and realize that you are being obsessed with what you can control, and not with the broader problem; you might instead ask yourself: how do I support overwhelmed intensive care units without shutting down the entire country?

In our early work on mental models, we established a theory about a ladder of reflection. Mental models can be:

- Level 1: A stereotype

- Level 2: A rule, such as “heavy rain causes flooding”

- Level 3: A conditional rule, such as “In terrain where the soil can’t absorb water, heavy rains cause local flooding”

- Level 4: Ad hoc reasoning: “This specific flood was caused by a combination of factors, such as terrain that can’t absorb water, coupled with sudden rain and waves from the ocean during the storm surge”

Reasoning starts with a spontaneous stereotype (you can’t help your brain popping those into your mind), recognizing that it’s wrong; and then working up the levels of reason towards an ad hoc causal chain: this is an exercise in awareness. The difficulty in doing so lies in the emotional blockages that get you stuck with one idea – something you can control. Panics and crises are so emotionally charged that we get easily overwhelmed and irrationally attached to the wrong solutions.

To move up the ladder of reasoning, we must teach ourselves to be problem finders, not solution givers. This is a radical mindset shift. As Nobel-Prize recipient Herbert Simon saw half a century ago, real-life problems rarely have one obvious solution. They are closer to the following structure:

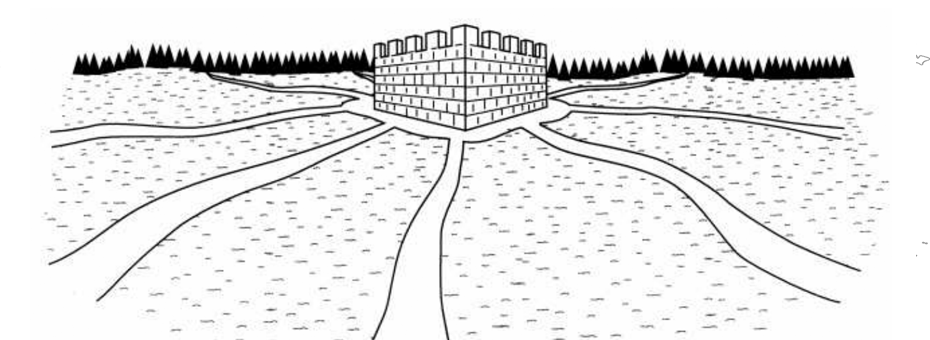

Source: Visual Abstraction in Analogical Problem Solving

The king wants to conquer the fortress, but there are many roads leading to it. Each road is mined, but to get supplies in, a small team can get through were a full body of men will trigger an explosion. On the other hand, any small party of attackers will easily be picked off by the defenders.

In any new problem, such as the coronavirus pandemic, no solution is the only one. All avenues work, but they are all, to some extent,fraught with difficulties. The fortress will fall if the attacking king coordinates small troops on all roads simultaneously and one wall eventually fails. This is how real-life problems get solved. By discovering and attacking all avenues, one stumbles upon the weakest constraint that can change the situation, and eventually cracks the problem.

Frame control means suspending your attachments, and releasing your brain from its obsession with a generic single solution. The broader Covid-19 problem was never masks/no masks – but from the start, what masks are where, and how do we procure them?

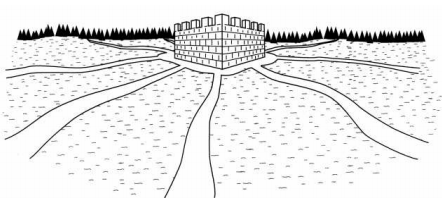

Decision-makers are bad at frame control precisely because they think their job is to make decisions early and quickly. Thus they instinctively follow the process of:

- Defining the situation: We might need masks but we don’t have enough on hand.

- Deciding on one option: Masks can’t be our priority right now, we’re going to have to forcefully keep people away from each other.

- Driving the solution through: Okay everyone, masks (or tests) are not the answer. The solution is to stay home.

- Dealing with the unexpected consequences: Now that we’ve done that, and havemany people living in areas without any visible contagion;and need to restart businesses;we will need to do that while explaining we were right all along.

This “take charge”approach is instinctive, feels good when you’ve got the reins (ha, look at me, I’m doing something), and is, often, ultimately catastrophic. Data comes in late, in the “drive” phase where you are already committed to a course of action and can’t backpedal. Unless you’re incredibly lucky, this is also the path to bad mistakes and making things worse.

To develop better frame control, we can train ourselves to an alternative way of reasoning. The lean thinking thought process goes:

- Find the problem: Look at the facts, talk to the people and keep discussing the issue until some agreement arises as to the true problems. Then, continue to keep that discussion open when new data arrives. In this case, how does Covid-19 really behave?

- Face the problem: Acknowledge to yourself the part of the problem you don’t know how to solve, rather then rushing to “solve” the aspects where you can jump to a blanket solution.

- Frame the problem: Spelling out the frame through which you look at the problem. In this case: slowing down the rate of infection of healthy people, slowing down the rate at which infected people get badly ill, and increasing hospital capacity to support a greater influx of respiratory critical care patients – without shutting down everything.

- Form solutions: Share the frame with everyone to build on local initiatives through inspiration and improvement. Encourage every hospital and every town to come up with its own plan to respond to the challenge and organize the communication structure that enables constant sharing of what works or not as new data comes in that clarifies find. Build solutions as we go, understanding progressively what can stay the same and what will need to change.Provide support and resources to local organizations when needed.

This lean way of thinking is less spontaneous; and it is both more effective (leading to less costly mistakes due to early misconceptions), and more resilient, because people get involved in building solutions as opposed to have them imposed on them from on high. These solutions are also more effective because they vary according to local conditions, which enables local learning curves to learn how to deal with the problem everywhere, not just centrally.

Figure 1: from “The Lean Strategy,” Ballé, Jones, Chaize and Fiume, McGrawHill, 2018

Just-In-Time as a Real Time Reality Check

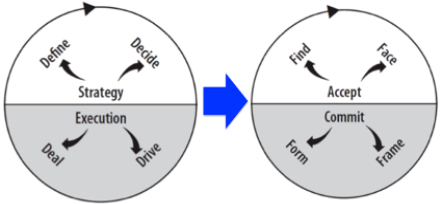

Just-in-time logistics is a key element of the “Find” phase of lean thinking. What we have seen in recent weeks is a series of supply chain failures and resulting panic. In hospitals, first not enough masks and not enough tests (which turned hospitals into hotbeds of contagion as staff got sick and people going in and out caught the virus and spread it); then not enough respirators, then not enough gowns; now we’re short on anesthetic drugs, and so on.

These shortages did not occur because stocks were too low. The shortages happened because we could not set up the requisite supply chains right away. Just-in-time thinking doesn’t force you to prioritize what you source now, but rather, which customers you serve while you build extra capacity. For masks, for instance, this means nurses and doctors first, then all caregivers, then the population at large. Thinking that way gets you working on increasing the capacity of the supply chain on day one, rather than remain stunned, like a deer in the headlights, wondering which way you should jump (i.e. which single solution will solve the entire problem, seeing that the obvious ones are out of immediate reach).

Just-in-time thinking and practice is a real-time sanity check, as opposed to what you believe is happening. It’s the reality of the situation – where supply is weak and threatened – and thus prompts us to quick action at the right place.

We still don’t know what we don’t know regarding this crisis. And committing early to blanket solutions is the worst thing we can do in a crisis. Doing so means that not only are we going to hammer the wrong nail, but at the same time we’re going to take way too long (having committed publicly to hammering the wrong nail) to discover the right focus for action. Just-in-time thinking keeps your mind open and flexible because the system itself tells you where the problem is, so that you can find out more about it as you work on solutions, balancing discovery and delivery as you go.

Figure 2: from “The Lean Sensei” Ballé, Chartier, et al., LEI, 2019

Path dependence is the worst enemy of smart resolution. Once committed to the wrong course of action – as new facts come to light – it’s harder to look up, rethink and change course, which is how every leadership disaster happens. Path dependence is also human and unavoidable, which is why we need to train ourselves to frame control with enabling tools such as just-in-time to respect people on the frontline and respect the facts they share about what is happening to them.

Mastering the path as opposed to being led by it, means looking up frequently to reevaluate both destination and way as new information comes to light. This can be a symbiotic, dynamic process involving all people. But to do so we must be free of our frames in order to control them.

If we seek the best outcomes for everyone (or the least worst), we must teach ourselves the discipline of being aware of the glasses through which we see the world and thoughtful about what they show us by digging deeper into causes, establishing consensus on problems and coordinating collective remedies.