As the 10th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina approaches this August, the lean principles of the Toyota Production System are changing how New Orleans and the U.S. recovers from disasters.

The nonprofit St. Bernard Project (SBP) had money to carry out its mission of rebuilding homes damaged by Hurricane Katrina. It had a warehouse with donated tools and building materials. It had steady streams of dedicated volunteers to do the desperately needed rebuilding work. It even had pioneered a new, more effective approach to disaster recovery. It also had a problem.

Its output of rebuilt houses had plateaued while the pipeline of people needing help rebuilding continued to fill. By 2009, four years after the huge storm hit on Aug. 29, 2005, there were 8,000-plus displaced homeowners in the New Orleans area still struggling to move back home, but who didn’t have money or insurance for repairs. Worse, they were being joined by an increasing number of homeowners who had suffered contractor fraud.

|

St. Bernard Project at a Glance

|

“We had to rebuild more houses,” said CEO and SBP co-founder Zack Rosenburg. “We had to do it faster and even more efficiently.”

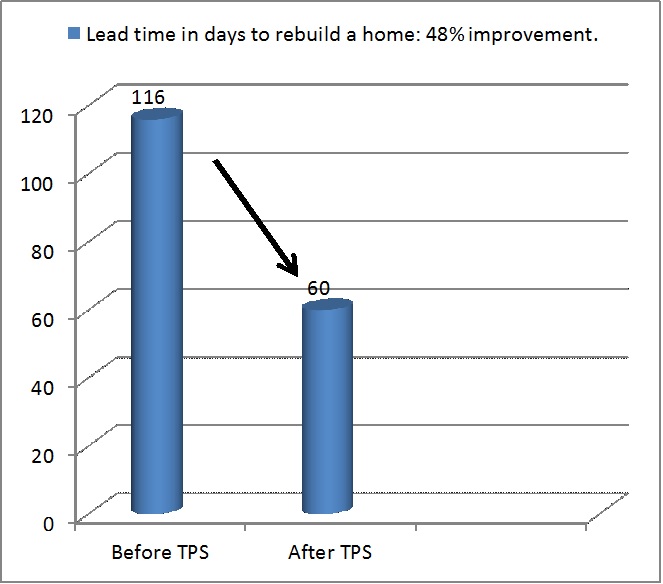

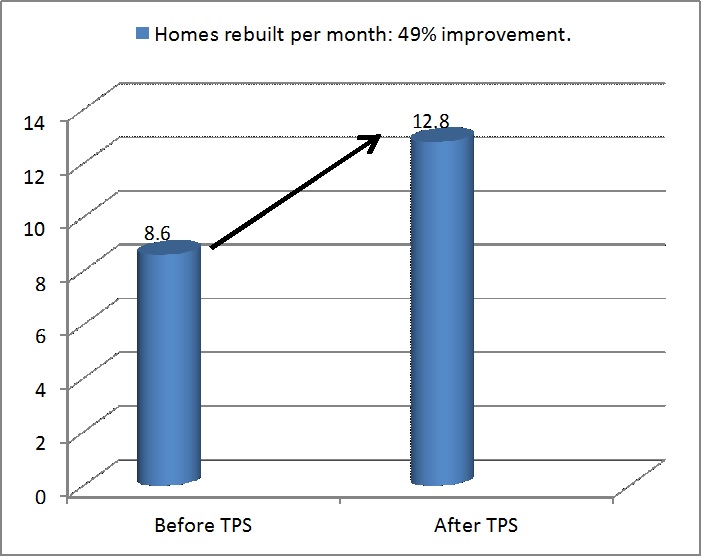

SBP tried assigning more volunteers to each home, working on more builds at a time, and hiring more contractors in an effort to cut the time from rebuild start to homeowner move-in. The roughly 116-day lead time barely budged. “We were stuck,” he said.

With help from the Toyota Production System Support Center (TSSC), they’d become unstuck, slashing lead time to just 60 days and dramatically increasing the number of quality homes rebuilt monthly.

Rethinking Disaster Recovery

Stuck was an unfamiliar condition for SBP. It had quickly built momentum rebuilding homes in its namesake St. Bernard Parish, engulfed by Katrina’s 25-foot storm surge, then a lingering five to 12 feet of standing water. The storm damaged or destroyed virtually every one of the parish’s 26,900 homes.

Much of the early momentum came from SBP’s new approach to rebuilding homes after disasters. Six months after Katrina hit on August 28, 2005, Rosenburg, a criminal defense lawyer, and Liz McCartney, a teacher, drove to St. Bernard Parish from their home in Washington, D.C., to do volunteer work. Expecting to find a recovery effort winding down, they instead found people still sleeping in vehicles, garages, attics, and overcrowded government trailers.

After two weeks of volunteer work, they thought homeowners surely would soon be moving back. They figured “we will find out who was building homes, and then go home and raise money for them,” recalled Rosenburg.

While fundraising, they learned how traditional disaster recovery worked. Rebuilding began after all the damaged homes in an area were gutted, a process that happened block-by-block. “We thought that was silly” said Rosenburg. “If our family was affected, we’d want someone to rebuild right away.”

Frustrated by the slow pace of recovery, they decided to move to New Orleans to help out. They tapped savings, left their jobs (Rosenburg commuted between New Orleans and Washington for a year-and-a-half), and by June 2006 were working full time as volunteers rebuilding homes. “It was the right thing to do,” said Rosenburg. But something just seemed wrong about how disaster recovery was organized.

Traditionally, separate organizations and trades managed each function, such as fundraising, case management, construction projects, coordinating volunteers, etc. Rosenburg and McCartney, as rehab rookies with an outsider’s insight, concluded that recovery would move faster if one organization had responsibility for the entire rebuilding process. Using money they had raised, they founded the St. Bernard Project as a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, dedicated to rebuilding homes with a vertically integrated, all-under-one-roof model.

SBP’s recovery model combined volunteer workers, subsidized labor from AmeriCorps members, and a handful of in-house skilled trades-people to do the entire rebuilding process from gutting, mold abatement, electrical, plumbing, drywall, mudding, painting, etc. SBP supplements its workforce with subcontracted plumbers, carpenters, and electricians as needed. To control insurance costs, the more hazardous work of roofing and foundation repairs are always done by outside specialists.

This “all-under-one-roof” approach saved time and money by exercising direct control over scheduling and the normally siloed skilled trades. It also gave clients one point of contact.

The “lifeblood” of SBP’s model, according to Rosenburg, are the 140 or so AmeriCorps members it gets annually for 10 months in overlapping shifts, split among disaster recovery sites in New Orleans, and, after Superstorm Sandy in 2012, in New Jersey and New York. They serve as construction site and warehouse managers supervising the work of volunteers, many of whom have no construction experience. They also schedule volunteers who come for days, weeks, or a month and work as client services coordinators. Some AmeriCorps members are skilled trade workers.

“Some have had graduate degrees, some are right out of college, some are retired people,” said Rosenburg, noting that SBP puts a special emphasis on recruiting returned war veterans. “We have had nuns too.”

AmeriCorps members are different ages, hail from different parts of the country, but all get $11,000 for 10 months “and they work their tails off,” Rosenburg said.

Not only does the SBP model handle the entire rebuilding process, it doesn’t wait until a “batch” or block of homes has been gutted. It rehabs homes one at a time.

The new model produced results. In its first year-and-a-half of existence, SBP completed the rebuilding of 88 homes, more than any other entity. For example, during the same period, the long-term recovery committee using the traditional approach had allocated funds for work to begin on 13 homes, noted Rosenburg.

The Challenge

Output kept increasing for about five years, hitting 100 rebuilt houses in 2011, before hitting a wall. “We knew we could work smarter and increase our rebuilding capacity, but we needed help figuring out how,” said Rosenburg.

He had learned that TSSC, a nonprofit arm of Toyota’s North American manufacturing and engineering operations, shared its manufacturing and process improvement knowledge (known as the Toyota Production System) with nonprofits and small to mid- size manufacturing companies. Rosenburg made a call to a Toyota executive who had recently visited.

|

Toyota Production System Support Center at a Glance

|

The next visit by Toyota advisors was typical of how it works with clients. Having previously gathered by phone some basic information about work processes and organizational objectives, they went right to the “shop floor” to observe existing conditions.

“In St. Bernard’s situation, the shop floor was out in the field and their processes were very challenging to visualize,” said Scott Porter, a Toyota project manager. With 15 to 30 homes in various states of repair at any given time, it was difficult to know what homes were on schedule, ahead, behind, and why.

McCartney, co-founder and now director of construction, recalls one of the first meetings with TSSC staff. They emphasized being able to quickly gauge the status of work and any problems. “They asked me are you ahead or behind? I looked at him and said, ‘Of what?'”

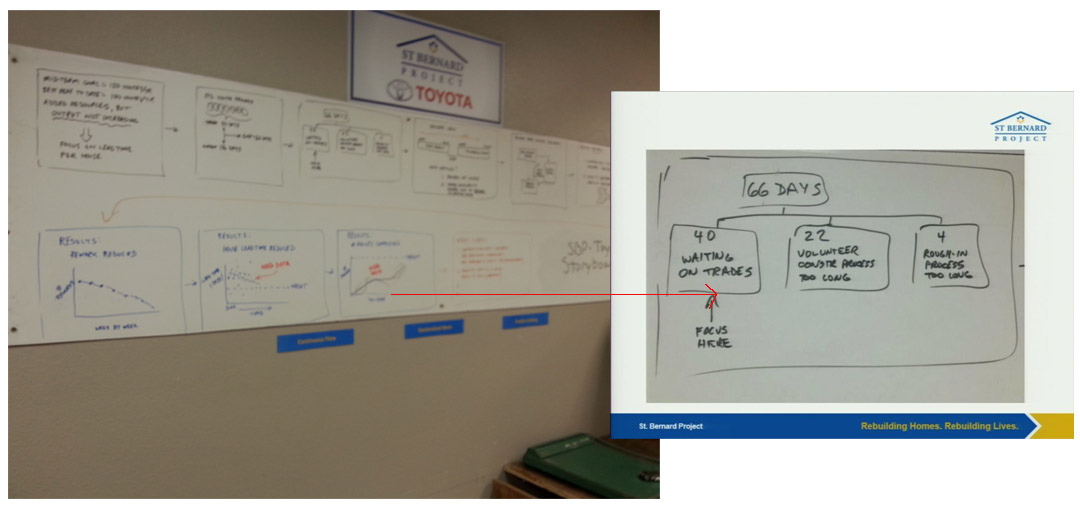

To start, a team of Toyota advisors and SBP managers analyzed work data and observed how work was done. The results – mapped on the construction office wall for all to see – identified where to focus the initial improvement effort. In order to cut lead time on a standard re-construction job from about 116 days to 50 – the pace needed to reach the annual goal of rebuilding 80 homes – SBP had to eliminate 66 days of lead time. The biggest delay, 40 days on average, was waiting for skilled trades, such as electricians, plumbers, and carpenters.

A big wall map posted on the exterior wall of the construction management room displays major

home rebuilding steps and lead times, making it obvious where bottlenecks were and where to

focus improvement efforts.

McCartney later reflected, “We had some great skilled trade teams both in-house and as subcontractors, but it was really hard for us to track what they were doing and how well they were doing the work. There were a lot of people working really hard but there wasn’t a way to show at any given time how all the projects were progressing. It was the squeaky wheel that got the oil – which ever project manager needed somebody the most, that’s where the trade teams would go.”

The analysis identified another main contributor to long lead times – rework. “A lot of it was due to not everyone operating with the same definition of what were our construction standards,” said Rosenburg. For example, how long should electricians take to do their jobs; what does a good roughed-in electric outlet look like? For the volunteer workforce, what does properly installed insulation look like, how do you texture wall paint?

The map along with training from TSSC in Toyota Production System know-how, helped SBP management and staff understand what to do to work smarter: make processes visible to identify problems, set standards, eliminate rework.

Improvements Implemented

Identifying problems starts every morning at a daily meeting where McCartney and project managers literally “see” what projects are ahead or behind schedule. They meet in the construction management office, a big room covered nearly wall-to-wall with boards that make processes — and problems — visible.

The process flow board, consisting of three white boards hung side-by-side and running the length of a wall, displays the three main stages of rebuilding work — pre- construction, skilled trade work, and volunteer work. Across the top row of each board, the team placed yellow magnetic labels corresponding to the construction phases within each stage. They arranged the magnets in the sequence each phase occurred. For example, the top row on the volunteer stage goes from insulation, to drywall, to interior paint, and so on.

Under each magnet, team members wrote in black marker the time each phase should take. For instance, the pre-construction board reads nine days for estimating, two days for roofing, one day for insulation. The times are based on experience and SBP’s rehabilitation goal of 80 homes annually. Below the times, large squares drawn in marker hold a data card for each house and represent SBP’s capacity for each phase, based on the goal.

The boards clearly show a bottleneck on the first board where cards are bunched in preconstruction phases such as estimating, funding by state and federal agencies, and vetting homeowner income. “You can see this is where our biggest backlog is because we are waiting for clients to be released for certain grants,” said McCartney. Reconstruction grants come from the city of New Orleans and the state of Louisiana.

To be eligible for grants, clients must be homeowners who have a source of income – job, pension, social security, etc., — but not enough cash to fund rebuilding themselves. “They have to have enough money for bills, expenses, and insurance but not enough money to hire contractors,” explained Rosenburg. Homeowners pay back a portion of construction costs over time.

The process flow board delineates the three main construction stages and the phases within each

with lead times and capacities.

Ahead or Behind?

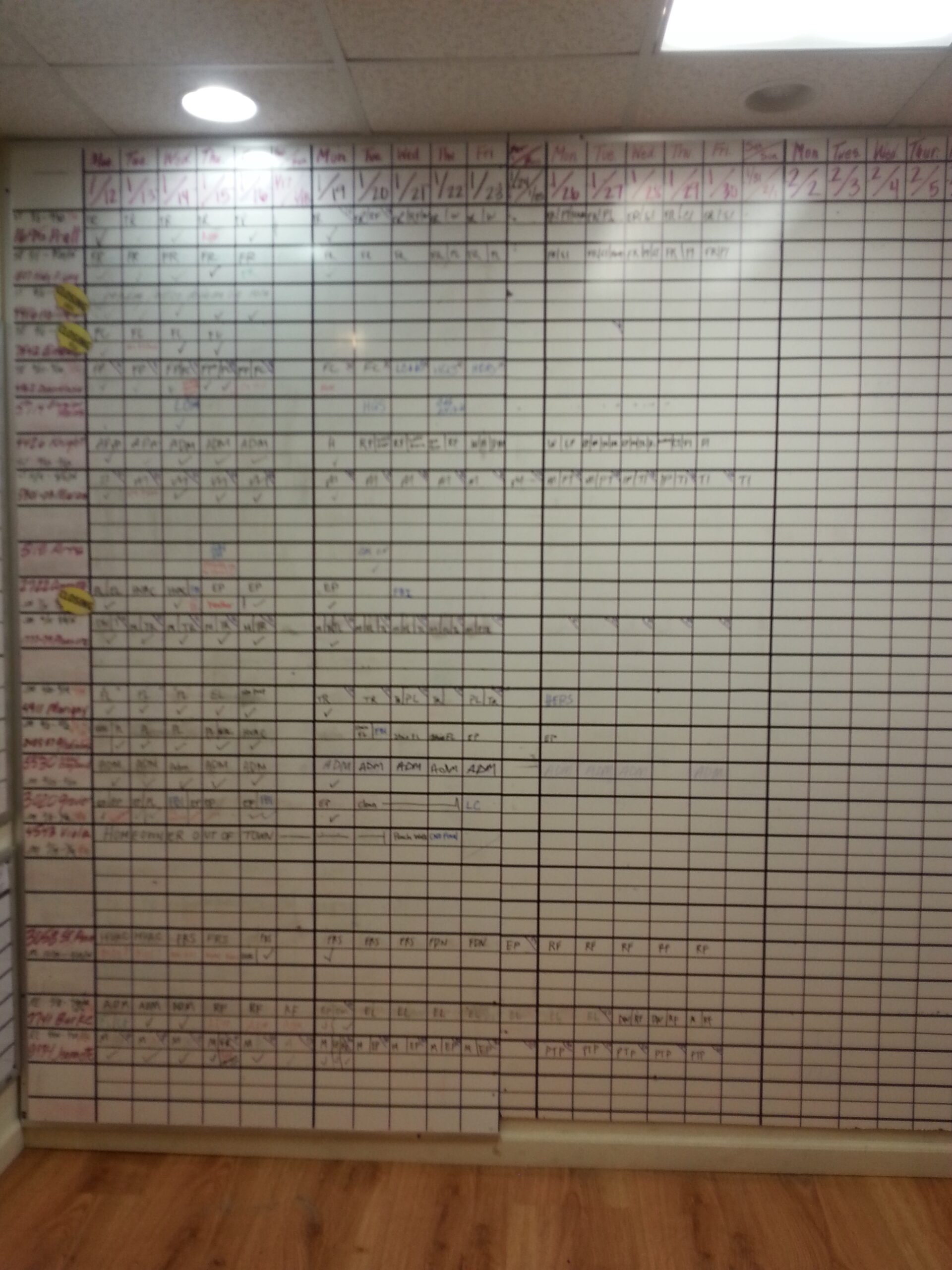

In a corner of the room, the process flow board meets the construction management board, a floor-to-ceiling display of daily work at every house under construction.

Horizontally across the board’s top row, staff members wrote in dates and days for a running four-week schedule, covering the week just passed and three weeks out. Down the far left column, they listed the addresses of homes being repaired.

In the resulting grid, the team wrote the work scheduled each day for each house. For example, “DW” in a box for a certain day means “drywall” is scheduled. A black check mark in the box underneath means the work was done. If it wasn’t, comments in red give the reason why. For example, when LEI visited SBP, a box in the fourth column of the board pictured below was marked “EP” for “exterior painting.” A red comment noted that it had rained that day. AmeriCorps volunteers and SBP staff maintain the boards.

The construction management board shows if work on each house is ahead or behind schedule.

The yellow bursts at the left indicate houses ready for final inspection.

Reporting Rework

Across the room from the process flow board, an AmeriCorps member logs and tracks rework on two small white boards hung side-by-side. If a homeowner calls about a problem within the one-year warranty period, the volunteer writes the date, address, and problem on the left-hand board. A site supervisor and repair due date are assigned and entered on the board. The right-side board aggregates problems by type, such as electrical, plumbing, etc., to identify patterns so corrective action can be taken.

![]()

A pair of boards makes rework reports and trends visible.

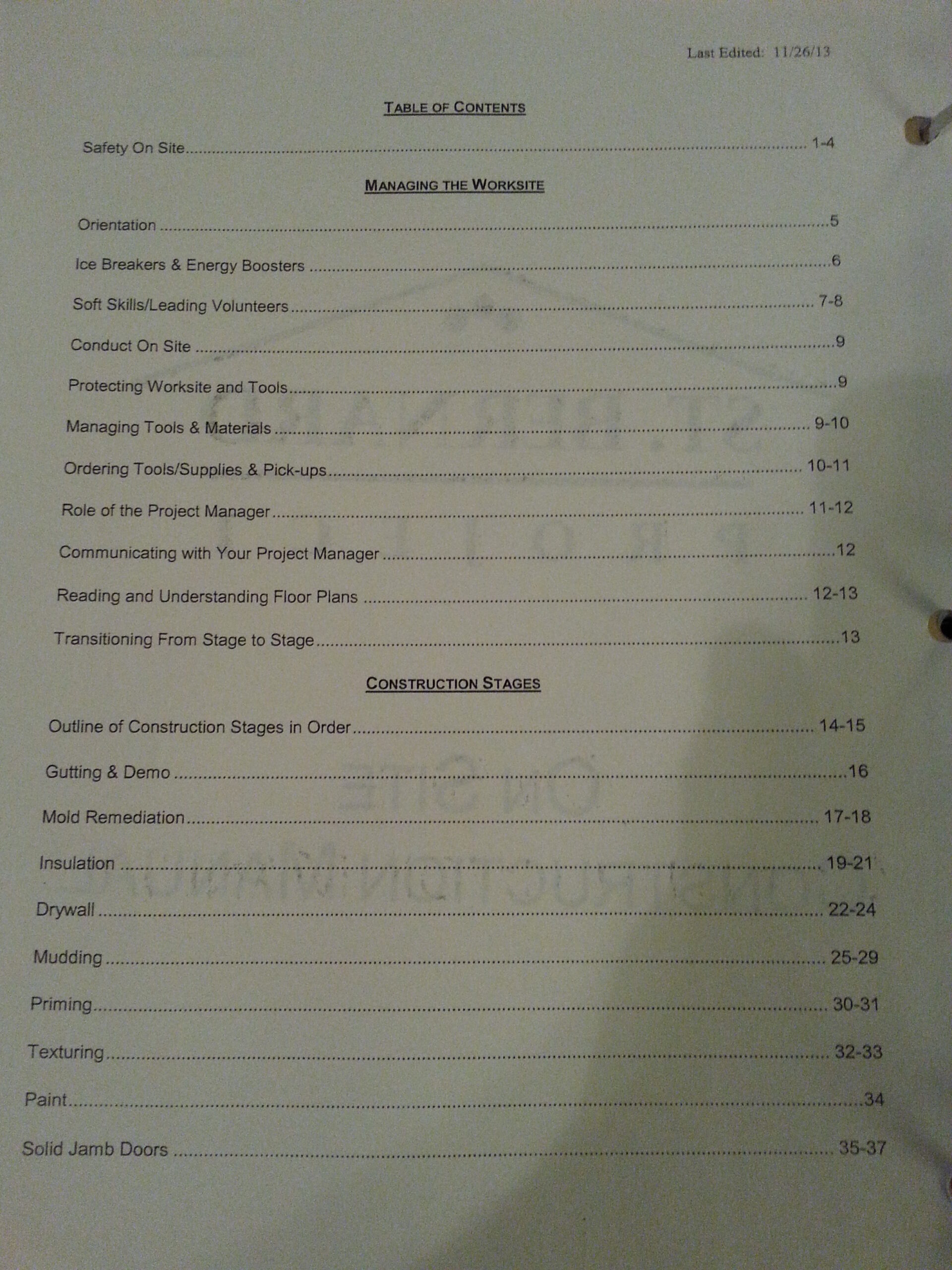

With TSSC coaching, the SBP team also standardized work at construction work sites and made the standards visible. The team developed construction manuals, three-ring binders with the steps, tools, and materials for every construction phase. Text, pictures, and checklists explain the right way to do every job. If a volunteer or supervisor has a question about hanging a door, for example, they check the manual.

Besides work instructions, manuals contain sections on safety, tool management, how to order supplies, and soft skills like on-site behavior and leadership. Manuals for every home are customized with sections for floor plans, scope of the work, costs, plus a biography of the homeowner.

“It’s very important that volunteers understand the work they’re doing will impact a very specific human being,” said Rosenburg.

Construction manuals at each site contain standardized work in text and pictures for every job volunteers or skilled trades-people will do.

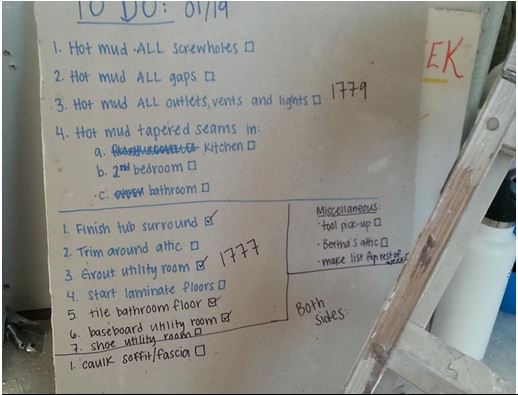

Who needs a white board? A scrap of sheet rock serves the same purpose at a construction site. It lists all the tasks for volunteers to do that day to adhere to the schedule on the construction management board at the main office.

After a few days of training to learn the SBP model and culture, prospective supervisors from AmeriCorps work on one house for about six weeks, doing every job in every construction phase. They meet every Wednesday evening with project managers, who are full-time SBP staffers, to talk about problems and share information.

5S for the Warehouse

Site supervisors also order construction supplies but occasionally were not receiving what they had ordered from the SBP warehouse, located a few doors away from its main office. Other logistics problems included:

- Out-of-date information about what was required at construction sites caused work delays.

- No inventory control system led to stocking excess and obsolete material.

- Inadequate tracking, sorting, and storage made locating tools and materials difficult.

- No daily meeting for sharing information or discussing problems and safety.

For reconstruction to work in the field, TPS had to be applied to warehouse processes. A warehouse team learned the “5S” principles of sort, set in order, shine, standardize, and sustain from Toyota advisors. (SBP added a sixth “S” for “safety.”) Then the team created standardized work processes with visual cues to quickly and easily identify abnormal conditions so corrective action could be taken. It organized tools and materials in clearly marked spaces and developed an efficient walking route for picking items needed on sites and staging them on the loading dock.

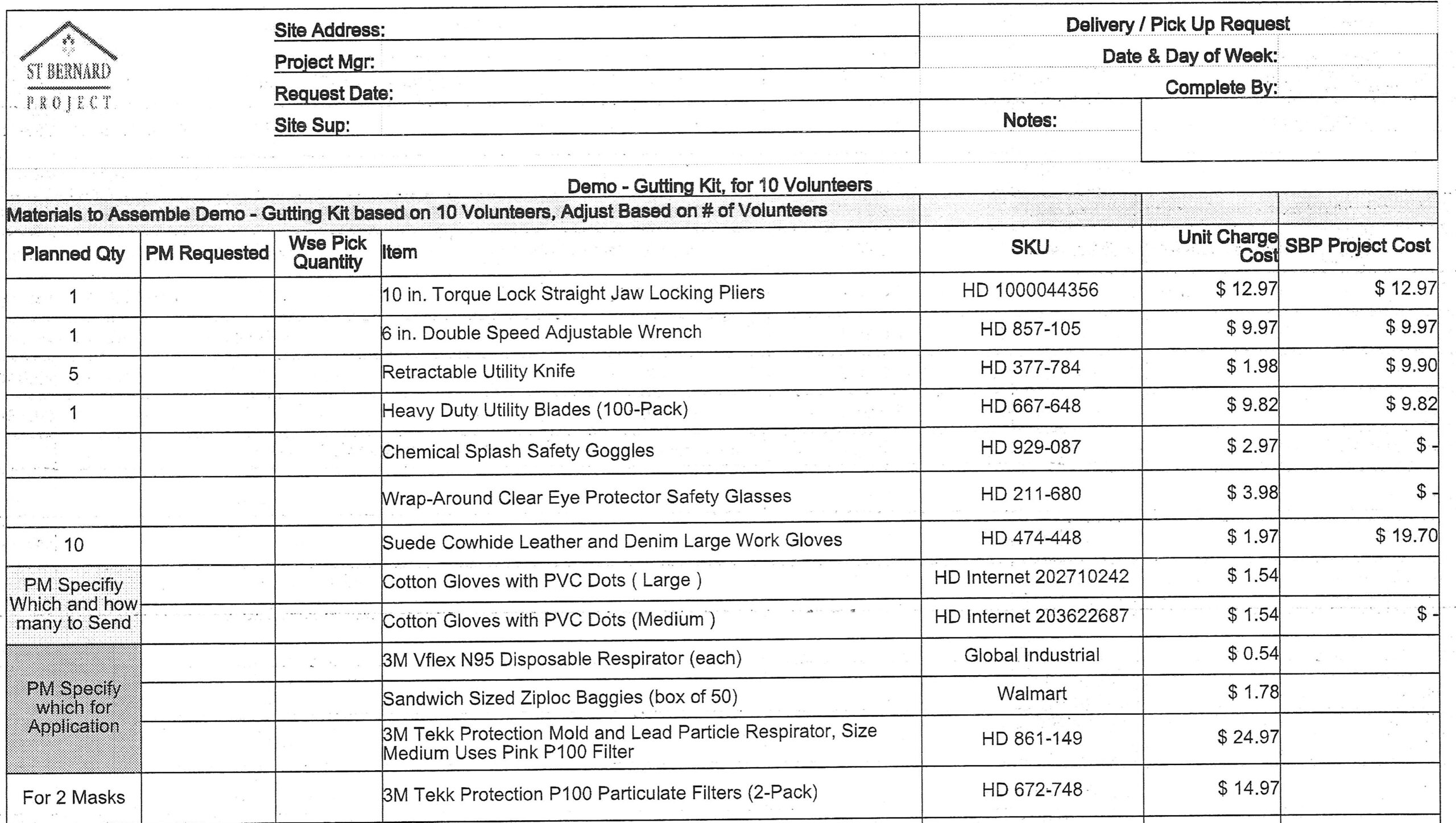

The team also standardized forms for ordering materials based on construction phases. For instance, if a house interior is scheduled for gutting, a project manager fills out the “gutting kit” pick sheet, which itemizes all the tools and materials volunteers will need on site. Everything on the sheet is listed in the sequence a warehouse team member will pick them.

“We try to make it as easy as possible for our team to get what they need,” said AmeriCorps member Shannon Cronin, warehouse supply and logistics coordinator.

Clearly labeled and well-organized storage areas in the redesigned warehouse made the

job of finding tools and materials ordered by work site supervisors fast and easy for warehouse staff.

A section from a gutting kit order sheet.

Order sheets are posted by delivery day and house address on a schedule board, where the seven-member warehouse team meets every morning for 10 minutes to review the day’s schedule, potential problems, and how best to schedule deliveries so everything arrives when needed.

“We’ll talk about what’s being delivered, how many people we need to deliver it, how many people are at the site to help, and do we have to make a pickup from a vendor” such as a home improvement center, Cronin said.

Throughout the day, construction site supervisors check in by phone with warehouse staff about work problems and progress. Every Thursday at 3:30 PM, the team gathers for a longer discussion about problems and ideas for solving them.

Standardized lists of ordered items are posted to the warehouse delivery schedule board,

the focus daily team huddles.

One discussion led to a more efficient process for restocking items. Every day after work, construction sites return tools and materials to the warehouse, using SBP trucks. Everything was unloaded and laid out on the floor inside a taped-off red square. Team members spent a lot of time picking through the pile, sorting, and checking the condition of items before restocking them.

After several experiments, the team developed a bin system. Returned items are unloaded but immediately put into dedicated bins, organized by warehouse storage locations. For instance, all paint, drywall, and flooring tools go into one bin; all safety and hand tools go into another. When a bin is filled, a material handler wheels it to the appropriate storage area. Tools in need of sharpening or repair go on a shelf above each bin.

Next, the team developed a visual cue to prevent mistakes. A sheet above each bin has pictures of what goes in it on the left side. On the right side of the sheet, arrows remind anyone sorting that the shelf above is for tools needing repair and the bin below is only for items “clean, sharp, and ready to use.”

The warehouse team developed a bin system with visual controls to restock tools and materials faster

and with fewer errors. A material handler has taken two full bins from the left side to storage areas nearby.

“Cary Grant”

To involve people from other departments in their efforts, the warehouse team asked site supervisors to name each ladder in stock. This not only involved supervisors in the process of improving inventory management, but reinforced the expectation that they were accountable for ladders at their locations.

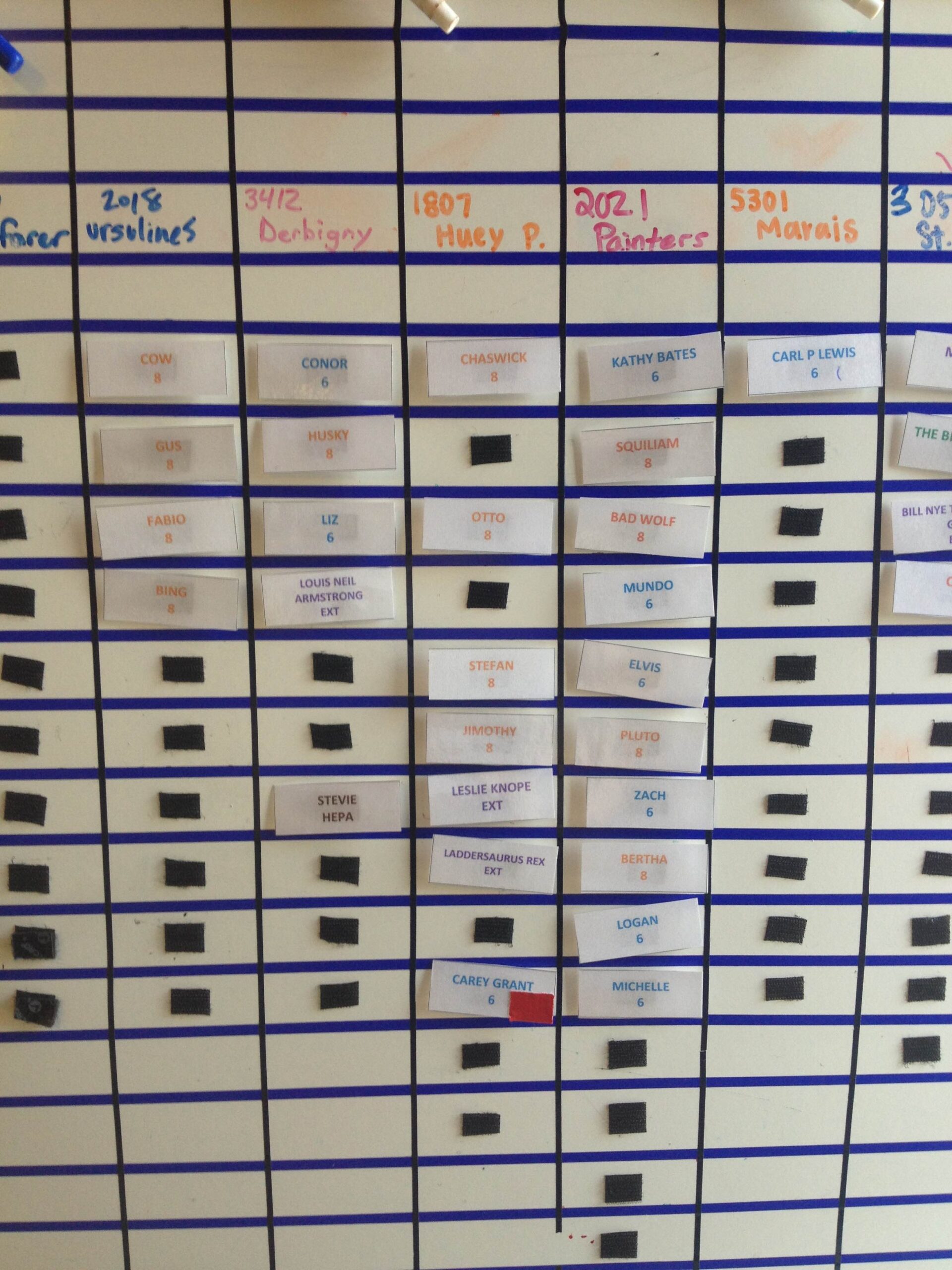

In the warehouse, ladders are stacked by size so the names written on them are visible. When ladders are transported to sites, their name cards are placed on the ladder inventory board in the warehouse. The board grid shows at a glance how many and what size ladders are at each location.

The ladder inventory management board uses name tags to control and track stock. Columns indicate the ladders at each address. At the top, color-coded addresses correspond to the site supervisor in charge. The red tag tells the warehouse team that the ladder “Cary Grant” has to be picked up from 1807 Huey P. Long Ave. for repair or disposal.

Constructive Discontent

Occurring simultaneously with changes to work, were changes to SBP culture, starting at the top.

At an early meeting with Rosenburg and his senior management team, a Toyota advisor asked if they were committed to implementing the new lean management system. All were. Then came the question, “Do you talk about problems?”

Rosenburg, seated in the front of the room, recalled “nodding vigorously.” Noticing the coach chuckling, he turned around to see “everyone shaking their heads no.” He realized that he ran SBP “the way a trial lawyer would – driven, focused — but not in a way that brought the best out of everyone or empowered the team to surface problems.”

Reflecting, Rosenburg said, “In retrospect, our work with Toyota was probably most instrumental in that we learned to talk openly about problems, and we learned to have honest conversations about whether we were ahead or behind schedule. This was a problem we didn’t even realize existed until we began this process.”

“We didn’t’ understand, he continued, “that the biggest ideas came from the ground floor. We really had to change our culture and identity to be an organization that got energy from talking about problems.”

The management team developed a “core ethos of who we are”, said Rosenburg, who summed it up as “constructive discontent.” It means management must position people to succeed by establishing high expectations with a system of clear accountability and support that encourages everyone at every level to discuss and solve problems.

Discontent means “if you are perfectly satisfied with results, you won’t change anything,” he explained. “If you’re not satisfied then you have to be willing to try things differently and you’ve got to be willing to struggle. We believe there is no progress without a struggle.”

Constructive means don’t “assassinate” your problem-solving ideas with a poor delivery, said Rosenburg. Staff is trained to deliver ideas in a way that is not a complaint, but is constructive and appealing to team members they are talking to.

“Constructive discontent is part of the St. Bernard Project’s identity and culture,” said Rosenburg. “What we do impacts people’s lives. We always have to improve.”

Rebuilding a Home and a Life

Sylvia Henderson can talk about the impact. She moved back into her home of 30 years the week before Thanksgiving, 2014, nine years after Katrina. “I was gone a long time, a long time,” she said, sitting in the dining room of her SBP-rebuilt home in the Gentilly section of New Orleans.

She spent the years living with relatives in other parts of the state as she dealt with a contractor, insurance companies, and relief agencies. Unlike many residents in the area who have been unable to rebuild because they lacked insurance, she was covered.

She said she paid $9,000, nearly the entire payout from a flood insurance policy, up- front to a contractor, who started but never finished rebuilding. And she still is in litigation with her homeowner’s insurance carrier over whether it was water or wind that ruined her home.

“The government gave us like $2000, which we had to wait to get,” Henderson said. But the process of getting help was exhausting and confusing. “Everywhere you went there were long lines. You had to get up like three or four in the morning or have somebody hold your spot because you couldn’t make it at the time. It was everybody at the same place at the same time.”

With the flood money gone, she started calling around to different agencies, looking for help to rebuild. One of the agencies put her in touch with the St. Bernard Project, which found grant money for her and organized construction. “They treated me with dignity and respect. I never heard an angry word. If I had to contact them for any reason they responded right away,” she said.

When they began rebuilding, SBP volunteers and trades people “pretty much took the house down,” she recalled, including the substandard sheetrock and plumbing work done by the first contractor.

Sylvia Henderson gets ready to hang a picture in her New Orleans home, rebuilt by

the St. Bernard Project.

She said the two-bedroom house now is in better shape than it was the day Katrina hit. “Oh I love it. Everybody loves it,” she said. “They come here and say, ‘Who did your work.’ Everyone admires the work because it’s really professionally done.”

She especially likes the modern touches like recessed lighting and the orange-peel texture of the pastel paint on the dining room walls.

Although she is back home, Henderson is not back to normal. The life she had in Gentilly with a close-by circle of friends, family, and church is gone.

A sister who lived nearby moved to Atlanta. A son who lived with her when the storm hit is still in Houston. Many neighbors haven’t returned and other things won’t be the same. “My church was right across the street, but after Katrina they closed it down.” She needs a ride to get to her new church.

“I’m still trying to rebuild my life,” she said. “I’m not there yet. The house was the first step.”

Results: Saint Bernard Project

A National Experiment in Transforming Recovery

The St Bernard Project (SBP) just may be the “model line” or pilot project for improving how communities anywhere in the U.S. recover from disasters.

Through its recently formed Disaster Resilience and Recovery Lab, SBP is sharing with other relief organizations and towns the lean recovery process that it and Toyota pioneered in New Orleans. The lab is funded by Zurich Insurance, and supported by Toyota, UPS, and Farmers Insurance.

The lab consists of two programs. One provides small to mid-sized businesses, homeowners, and municipalities in vulnerable areas training in risk mitigation. The other provides actual post-disaster rebuilding help by SBP teams or training in its lean recovery process to make local efforts faster and more efficient.

Since New Orleans, SBP has helped recovery efforts in Joplin, MO, devastated by a tornado in 2011, towns in New York and New Jersey ravaged by Superstorm Sandy in 2012, and areas of Texas struck by floods in 2015.

Links with relevant Information:

- Discover how the St. Bernard Project is changing disaster recovery in the U.S.

- Watch a TSSC video about the St. Bernard Project

- Volunteer or donate to the St. Bernard Project

- See all LEI lean case studies about a variety of companies and challenges