Students of lean are often confused by the variety of ways Toyota explains the Toyota Production System. For instance, what is the link, they ask, between the TPS house and the Toyota Way?

There is a lot of to learn and get your head around in all these various materials and, not surprisingly, people tend to latch on to one aspect or the other. But back at the gemba these two seemingly separate elements are not that separate at all. When we examine each one’s nature and intents, we can see that they form a symbiosis, i.e. we cannot have one without the other.

First let’s break down the two concepts:

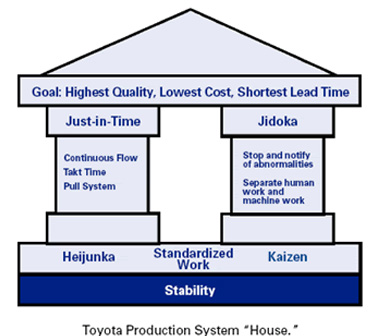

The TPS house, in its simplest form is about:

The TPS house, in its simplest form is about:

- Seeking competitive advantage through customer satisfaction

- By increasing the level of Just-in-time and Jidoka

- Through engaging people into heijunka, standardized work and kaizen

- Resting on a basis of stability

The idea in learning this is that we increase outcomes for

- Customers: with highest quality, lowest cost and shortest lead-time

- Employees: work satisfaction, job safety and security and consistent income

- Company: market flexibility and profitability (from overall cost reduction)

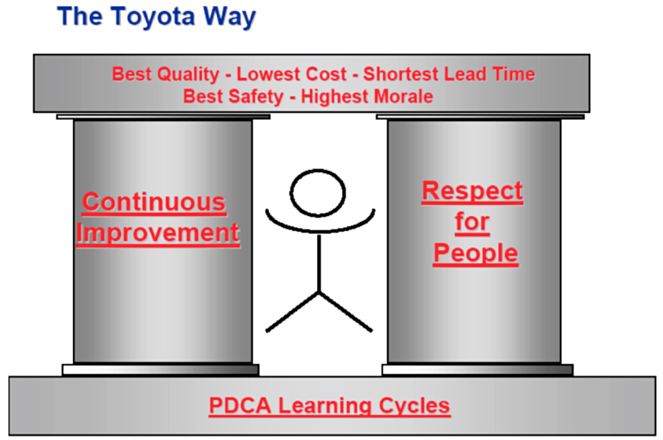

On the other hand, Toyota also formulated a management approach with the “Toyota Way:”

On the other hand, Toyota also formulated a management approach with the “Toyota Way:”

- Challenge: forming a long-term vision and meeting challenges with courage and creativity to realize dreams

- Kaizen: improving business operations continuously, always driving for innovation and evolution

- Genchi Genbutsu: practicing genchi genbutsu, going to the source to find the facts to make correct decisions, build consensus and achieve goals at our best speed

- Respect: respecting others and making every effort to understand each other, taking responsibility and doing our best to build mutual trust

- Teamwork: stimulating personal and professional growth, sharing opportunities of development and maximizing individual and team performance

Do they sound like they refer to different aspects of business? Probably. But let’s not lose sight of the fact that Toyota developed all its lean techniques in order to gain competitive advantage – and in doing so they transformed from the underdog into the top dog. There are many ways to take on the challenge of competitive advantage, and Toyota chose the angle of customer satisfaction as defined by:

- Quality (if you’ve missed it, check out Top Gear’s program on “how to kill a Toyota”)

- Variety – rather than restrict their range, Toyota constantly increases its offer for micro-markets by efforts to reduce lead-time through greater flexibility

- Reasonable price – by transferring waste elimination gains into more value to customers

- Energy performance – more recently the company is betting its future on offering its customers energy efficiency as well as quality, variety and price.

Each of these challenges requires, indeed, long-term vision, courage and creativity to avoid taking the easy way (as VW recently did with energy performance) and instead to continuously commit to create value through manufacturing and delivery of products and services.

The first pillar of the Toyota house, Just-in-Time, was originally defined by Kiichiro Toyoda’s insight that “the ideal conditions for making things are created when machines, facilities and people work together to add value without generating any waste.” In essence, this is about teamwork – solving problems across functional boundaries – and Toyoda created methodologies and techniques to eliminate the waste between operations, lines and processes, which would later be refined by the Kanban system and generalized across as just-in-time across the supply chain. This further stressed the need for teamwork with suppliers (and led to the formulation of the TPS house to teach suppliers how to fit within the just-in-time supply chain and benefit from it).

The second pillar (or the first if you read this right-to-left) has even earlier origins as Sakichi Toyoda originally invented a mechanical loom to first help loom operators work easier, and then free them from work altogether. The clever feature that allowed the loom to stop when a cotton thread breaks was meant to free the worker from having to babysit the loom. Today a loom, like your dishwasher, can work at the touch of a button, changing spools on its own and stopping when it detects a problem so you can continue with your value added work without monitoring it.

As the Jidoka concept developed, it included all various visual control techniques to visualize problems. This, in turn, hinges on a strong commitment to respect as executives are expected to go to the worksite and listen directly to what employees have to say about the problems they encounter. Issues are visualized, “why?” is asked repeatedly to seek root cause, and most importantly, unfavorable information is shared and paid earnest regard rather than concealed. The technical practices of Jidoka are deeply bound to the commitment to respect, hearing out each other’s perspective and creating the right conditions for every employee to succeed at their job through mutual trust, mutual responsibility and sincere communication.

Finally, the practice of kaizen and standardized work rest on the determination that every employee should be engaged in their own development and should actively participate in the design and running of their own workplace. Here again the values of responding on the gemba through teamwork and respect by small-step improvement are key to making kaizen and standardized work function. Similarly, the heijunka planning practices are all about creating the conditions for meaningful kaizen, both by leveling customer demand and requiring ever-further fractioning of batches and mixing of production.

Companies that seek to adapt the lean tools to their situation completely miss the point – lean tools are there to lean the company, to teach it a new way to think (i.e. lean thinking) through a new way to act (using the lean tools to see work differently). That’s why in the Gold Mine Trilogy Study Guide Tom Ehrenfeld and myself refocused on the tools presented across the three trilogy books. It helps study groups look and see how rigorously applied lean tools change the perception of what is actually going on at the gemba.

Of course, most managers resist simply because they subscribe to different values. At the gemba, why do so many executives prefer small gains from cost-down projects (with the associated risk of damaging customer perceptions of quality and delivery) to the huge windfall of cash improvements from better Just-in-time? Simple: It’s because cost-down projects can be pushed on others by a strong manager, whereas wall-to-wall pull systems require teamwork across all functions.

Why do executives choose to invest in expensive, over-capacity machinery or delocalization rather than create continuous cells? Because they dream of replacing people by equipment rather than respecting workers and using better Jidoka.

And last but not least, why do C-suite execs choose the yearly reorg over fixing problems one by one, regardless of the huge cost and disengagement this creates? Because they believe bosses boss and workers work and don’t realize that engaging people in the design and operations of their own workspaces could net much greater results.

In the end, the technical issues revealed by the TPS house principles can’t be resolved without also adopting the central values of the Toyota Way. Looking at work (and thinking) along the lines of the TPS house will show you the direction to lean your company, department or own work. It’s a call to action. Acting upon it, however, also requires understanding (and adopting) the deeper attitude changes needed to find leaner solutions to customers, employees and company challenges.