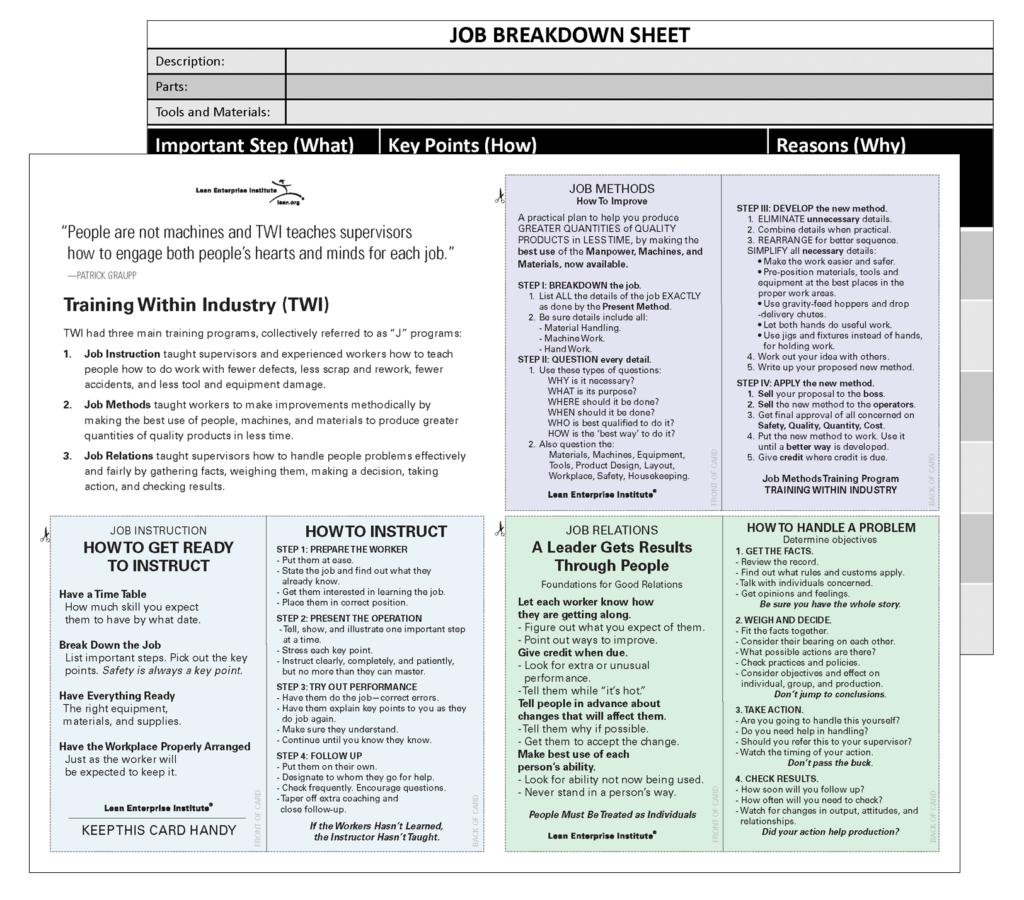

From the perspective of performance-based instruction and performer support systems, TWI (Training Within Industry) is a beautiful thing: PDCA-tested, simple, clear, direct, coherent, and comprehensive. It reliably turns subject matter experts into effective coaches, raises overall skill level and breadth, helps people grasp production flow problems, and even addresses the “socio” side of the socio-technical system in which production occurs. We are not making this up! They were doing role-play exercises on the shop floor in 1944!

For folks who don’t know much about TWI, first, a bit of history and why it matters:

Before entering World War II, the U.S. government began a concerted effort to transform consumer production into high volume production of wartime matériel. Over the course of the war that effort succeeded magnificently and was decisive in the war in the Pacific and important in the European Theater.

That transformation in production, particularly in the grand scale of its ramp-up when major portions of the workforce were shipping off to fight in the war, required that workers learn new skills rapidly. Key to this was the Training Within Industry (TWI) program, and we can trace TWI back – naturally – to the same roots that ultimately nourish Toyota Way thinking. One of those roots is John Dewey’s 1911 book How We Think, from which people like Walter Shewhart, and W. Edwards Deming drew PDCA. TWI itself had a large direct effect on Japanese industry after WWII, when it was introduced by the U.S. Occupation Authority to help rebuild Japanese production capacity. To appreciate the intense interest some Japanese industrialists had in TWI, recall that it was key to ramping up wartime production in the U.S.

But we get ahead of ourselves. Some months before the Pearl Harbor attack in December 1941, the Office of Production Management circulated a stylish, compelling booklet titled A Challenge – the equivalent of a slick PowerPoint deck today – to convince senior executives of U.S. industry to get on board with the program. Their revolutionary idea, born of necessity, was that industry would do the training, and do it well, by, and for itself. This meant not relying on traditional instruction sources or haphazard training (“content-based,” in the terminology of Jeff’s previous post). Importantly, TWI would not leave development of the instruction system to industry – professional instructional system designers would handle that – but the instructor/coaches would come directly from supervisors in the industrial Gemba and instruction would occur there.

That TWI pretty much evaporated in U.S. industry after the war has puzzled a fair number of people. Less well known is its history in Japan. After rapid uptake of shop floor TWI (the variant that made such a difference in U.S. wartime production), Japanese industrialists continued to support development and deployment of a follow-on system that took the approach upward in the organization to managers and executives. As we learn more about TWI’s role in the early development of TPS, we see the wisdom of companies like Toyota engaging top levels of management and making the methods an integral part of every segment of production.

Today, as companies rediscover TWI, they are proving that the formula for success that helped the Allies win WWII still works in today’s competitive international environment. At the LEGO Group, top management from the HR headquarters in Denmark have developed a learning organization using TWI to create and maintain global standards of operation at four plants in Denmark, the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Mexico. As we write this piece, a new plant near Shanghai is being built and TWI trainers are being developed to leverage the expertise already developed in the other plants. At the new LEGO plant, in order to be a future supervisor or manager, you must first learn and be capable of doing the work on the floor, then be able to train the people who will be working for you in those jobs. One thing we know for sure: While TWI skills are practiced right at the Gemba, the direction for this scale of global implementation must come from the very top of the organization.

So, how about TWI-21, Training Within Industry for the 21st Century? And this time, for the executives first. How about a program that does for senior leaders today what TWI did for Japanese management in the 50s in terms of ramping up everyone’s ability to respond to problems on the ground and overall effectiveness? In this still young new century, we must take the wisdom of the past and apply it effectively to the challenges of the new age. In so doing, we can bridge the gap between the Lean Sharks who rush to pull results out of a Lean transformation but fail at sustainability and the Lean Tortoises who take a decade or longer, too long for the fast pace of the 21st Century, to make true and lasting change.

Such a program might do the following:

- Take advantage of all the advances in performance-based instruction and performer support systems and bake in Toyota Way managerial knowledge work skill-building.

- Leverage social media for shared learning and structured problem-solving e.g., as a digital version of Toyota’s supplier self-support networks.

- Test the heck out of it before, during, and after deployment – have a Lean Startup experimental approach with rapid sprints pushing out minimum teachable skill features for feedback.

This would work to get us maybe 80% of the way to the kind of lean leadership skill development that previously could only be achieved by a small army of long-term expat, expert Japanese execs doing things totally hands-on. We would still need some very special humans, but they could help leverage this learning system, which means it could scale nicely after reaching development stability. This is what the TWI founders accomplished in a fairly short amount of time (albeit with a “gun to their heads”) during WWII. They created a “multiplier effect” by designing standardized programs that could be promulgated quickly and consistently while maintaining quality of the content.

The question is who moves this forward? For the TWI Institute’s part, it’s started and operated today as a subsidiary of one member of the Manufacturing Extension Partnership (MEP) Program run by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (part of the Department of Commerce). The Institute has consolidated TWI materials and delivery methods and developed a certification program based on the original WWII standards and what was accomplished by the Japanese in the post-war period. The key has been top management involvement, so much work in this area is still needed.

The talent is out there to kickstart Agile development of a top-first, learning-doing system that leverages TWI’s proven ability to promote Lean Transformation. So what do you think? Who is already moving something like this forward? Who might be interested in reviving one of the shining jewels of America’s past, one created by the government with and for industry?

Download the Free TWI Reference Guide

Investing in Work(ers) Using Job Methods and Job Instruction

Learn how to develop team members for sustained success.