Can you have a culture of excellence and not have a culture of improvement? Don’t they go hand in hand? Not necessarily. Just ask anyone who works in healthcare, where superior clinical outcomes and exceptional patient experiences too often reflect individual efforts to work around the system, not within it.

“The problem with having a culture of excellence is that you have people who are trying very hard, but they don’t always organize themselves into effective teams or create efficient processes,” says Dr. Lisa Yerian, director of hepatobiliary pathology and medical director of continuous improvement at the Cleveland Clinic. “People who are committed to excellence can create a lot of workarounds. They will go the extra mile but don’t always think about how to go three miles fewer to deliver the same or better quality care.”

People who are committed to excellence can create a lot of workarounds. They will go the extra mile but don’t always think about how to go three miles fewer to deliver the same or better quality care.

Imagine if you could create a culture of excellence and improvement in a large healthcare organization. That’s the challenge that pushed the Cleveland Clinic to reinvent its continuous improvement program and push for a true cultural transformation.

Rolling Start

Few organizations, in healthcare or otherwise, can match the Cleveland Clinic’s culture of excellence. Located in Cleveland, Ohio, it has been one of the top-ranked healthcare systems in the United States for decades and continues to pioneer new medical breakthroughs every year.

System-wide it employs more than 43,000 “caregivers,” including 3,000 salaried physicians and researchers, and 11,000 nurses. They follow a patient-centered model of care organized by departments and institutes, which focus on a single organ system or disease, upending the traditional hospital structure based on medical specialties.

The Cleveland Clinic launched a formal continuous improvement department in 2006. The department began by helping different cross-departmental teams with collaborative problem solving and performance metric reviews. Its activity and scope expanded in response to internal demand.

Growing slowly over the next six years, the CI department recruited new team members from a variety of industries eager to apply their knowledge of Toyota business practices, lean, six sigma and project management to the healthcare realm. Embedded in the departments and institutes, they worked with cross-functional groups to apply classic problem-solving methodologies and tools to a list of high priority projects.

These discrete projects had a significant and sustainable impact on quality, the patient experience and costs in a variety of settings within the Cleveland Clinic. Some examples include:

- Oncology: A cross-functional team reduced outpatient chemotherapy wait times from an average of 60 minutes to 20 minutes.

- Operating Rooms: Faster setup and turnaround times maximized operating room utilization.

- Emergency Department: Split-flow triage paths dramatically reduced average wait times and the number of patients who ‘left without being seen.

- Pathology: 3P and other lean design methods engaged the workforce and improved efficiency during the construction of a new pathology lab.1

Continuous Improvement Challenge

Such projects continue today. They’re often focused on improving timeliness of care by reducing patient wait times or eliminating waste to make the care they deliver more reliable and affordable. But as beneficial and important as these focused projects are, they don’t necessarily instill a problem-solving mindset, or the skillset to solve everyday problems, among the Cleveland Clinic’s thousands of caregivers. In the fall of 2012, Dr. Robert Wyllie, the chief medical operations officer, challenged CI department leaders to build a culture of improvement.

“We needed to change the culture so that everyone was thinking about it, teach them some basic tools and a basic approach, and drive responsibility for changes to every caregiver. We had to give everyone the opportunity to look at how they’re doing their day-to-day jobs and where they could make improvements, reduce wastes, cut costs and improve the patient experience,” says Dr. Wyllie.

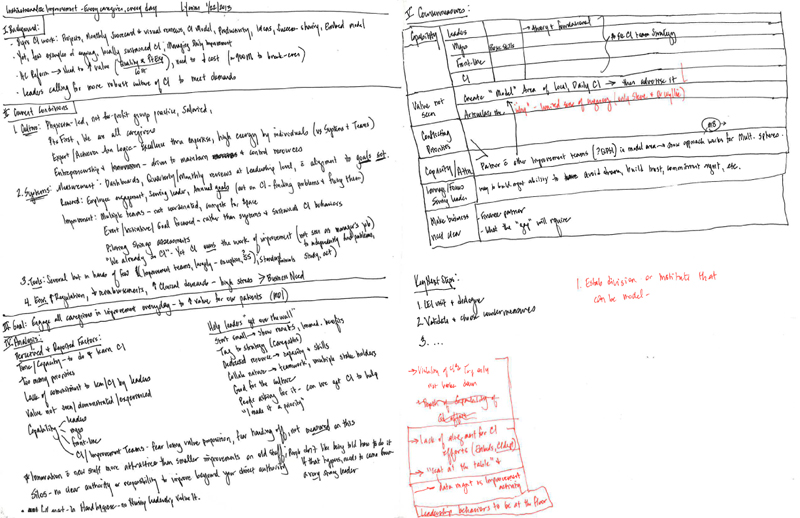

Dr. Yerian and I had a long discussion about the state of continuous improvement at Cleveland Clinic,” Reich said. “It was obvious to both of us that there was a gap between the isolated islands of improvement that were occurring and a sustainable system-wide culture of continuous improvement. Any time a clear gap like this exists, there is the opportunity to further clarify that gap and study countermeasures in the form of an A3. That’s one of its primary purposes.

But how do you actually go about creating a culture of continuous improvement? When Dr. Yerian posed that question to Lean Enterprise Institute COO Mark Reich, he said it sounded like they needed to create an A3 report around it.

The A3 turned out to be the perfect tool for tackling such a multifaceted question. Everyone had an opinion of course, and many of those opinions were highly political. Changing the culture would extend well beyond the CI department. It touched the organization’s management systems, reward systems, and data systems; it would ultimately be reflected in how people talked about and tried to solve problems. Incorporating input from many people and departments, the culture change A3 went through more than a dozen iterations.

“We finally settled on capability as a fundamental contributor to creating a culture of improvement,” recalls Dr. Yerian. “You need a certain level of capability to understand how to solve problems effectively and to understand what the most important things to work on are. Our caregivers need to be capable of identifying and solving problems, with support and coaching, as part of their everyday work. If we could impact capability, we hypothesized, we could impact our culture.”

That was the hypothesis for creating a culture of excellence and improvement. Like any hypothesis, it had to be tested. And, for it to spread, people needed somewhere to go to see for themselves what such a culture looked like and how it worked.

STRATEGY A3 ON HOW TO CREATE A CULTURE OF IMPROVEMENT

The Number One Criterion of a Model Area: It Has to Work

Around this time the impact of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) on the revenue models of healthcare organizations was coming into sharper focus, recalls Chris Donovan, executive director, Enterprise Information Management and Analytics.

“In early 2013 our CFO Steven Glass told me we had to figure out how to take 12 to 14 percent of our costs out. That wasn’t something we could do just by asking people to work harder,” he explains. The rate of improvement had to accelerate dramatically. There simply weren’t enough CI people to support all of the work that had to be done.

“You can do SWAT-team improvement projects, but that doesn’t change how people think. We had to change the way we lead. We had to empower people to find efficiencies and solve problems on the fly. We had to change the way we approach our work,” Donovan adds.

You can do SWAT-team improvement projects, but that doesn’t change how people think.

To test the A3 hypothesis, Donovan’s group, Decision Support Services (DSS), which is part of the finance division, became the first model area for how a culture of improvement might operate on a day-to-day level. The group is located in an administrative building in a suburb south of the main downtown campus. With the industry-wide push toward value-based care and an increased emphasis on efficiency and costs, it was a fortuitous place to start. The decision support group generates the monthly patient care and financial reports that managers at all levels use to track performance. Basically, they keep score for the entire Cleveland Clinic organization.

Kicking off in May 2013, the initial focus in the DSS group was on problem solving. That started with learning how to create and use an A3. An expert from the CI department trained two “lean leads” from each of the group’s four teams, who then trained their teams. They rolled out other lean management and problem-solving tools in a similar fashion, always emphasizing the connection with the scientific method through the PDCA (plan-do-check-act) cycle.

Rather than follow a cookie-cutter approach or do comprehensive across-the-board training, the CI department tried to introduce methods and tools to the DSS teams only when they were needed. That way they weren’t introducing solutions to problems that hadn’t arisen yet. The approach was less didactic and more purposeful than many introductions to lean principles because it focused on providing solutions to real problems that the team was facing.

For example, when the DSS group implemented a kaizen suggestion process, it generated a flood of ideas. To prioritize those ideas managers realized that they needed a better understanding of the strategic priorities of their department and the Cleveland Clinic organization as a whole. They could then align improvement activity accordingly. To do this they utilized a strategy deployment tool first developed in the 1950s known as OGSM (objectives, goals, strategies and measures).

“Building these capabilities is highly engaging; it’s fun and really connects with people,” says Dr. Yerian. “But in order to provide value the work has to be connected to the priorities of the organization. The organization’s leaders need to see that the problems the teams are solving are those that are most important to them.”

This strategy deployment work was one example of the lean leadership capabilities that the Cleveland Clinic had to develop in parallel with the core problem-solving approaches and tools. During the weekly CI reflections, in addition to practicing and modeling coaching behaviors themselves, Dr. Yerian and Chris Donovan—who separately attended LEI lean coaching and leadership workshops—would give managers and executive directors feedback on how they posed questions to their teams, and how they discussed and recognized results.

“If we had just taught the frontline how to solve problems, without changing the way we lead, it wouldn’t have gone anywhere,” says Dr. Yerian.

Utilizing the problem-solving tools, implementing countermeasures and continuing to follow the PDCA process, the decision support group started to find permanent solutions to intransient problems and began to make dramatic performance improvements. During the first three months, they documented 130 kaizens (approximately one per person per month), saving over 1,600 hours. When the initiative began, they were rarely hitting the monthly target date for releasing the monthly financial reports. Today, they always hit the target, and expect to get the reports out a day earlier this year.

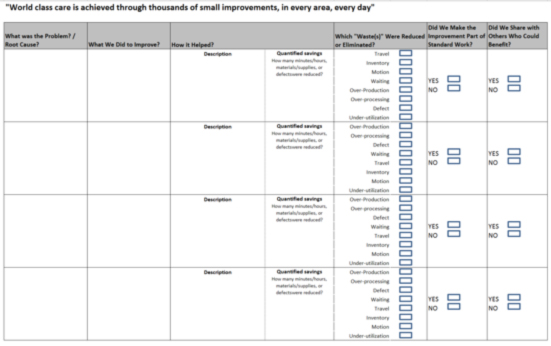

Kaizen Capture

One thing the DSS team learned is that as improvements unfold and multiply, it’s easy for people to forget where they were prior to initiating their lean journey and lose track of the progress they’ve made. Now every model area team tracks their kaizen activity on a simple reporting form (above) to document the value and impact of their improvement activities. Capturing such gains also supported reward and recognition efforts, sharing of best practices, standardization, and ongoing reflection.

To confirm that the targeted capabilities were being developed and that the teams were making progress, they reported on their activity every Friday to senior department and CI leaders. In addition to results, the leaders looked for knowledge development and lean management behavior, according to Dr. Yerian.

Today, evidence of this expertise is demonstrated by the variety of visual management tools being used in the department every day. Members from the DSS group come together for a stand-up huddle at 9:45 every morning. Reviewing project status and key metrics on the performance boards, they talk about issues from the previous day, potential problems, and countermeasures. There are always issues to address because data processing times vary, sometimes considerably, depending upon what might be running on the servers. Each daily huddle ends with an around-the-room check in when anyone can bring up any questions or issues.

In addition to dramatically cutting down on email, the daily huddles have tightened the links between the four teams in the department. People are much more aware of the impact their work has on the next person down the line, and are therefore more accountable to the overall department goals.

In less than two years, the DSS group’s efforts enabled the team to reduce their costs by over 10 percent. As efficiency improved, no one was laid off; staff size was reduced through attrition. In addition to costs, the group improved service levels, quality and responsiveness as well. Productivity gains increased capacity as internal demand for new and more advanced performance reports and analytics increased.

Today Finance, Tomorrow the World

As the first model area the decision support group made a commitment to welcome visitors from other parts of the Cleveland Clinic organization to come and see what they were doing, to talk candidly about what worked well, and to share what some of the challenges had been. The lean leads are also helping to spread the problem-solving capabilities to other departments. This takes some of the burden off of the CI staff, which is currently made up of only 32 people in an organization of more than 40,000 total employees.

“We wanted to create a ripple effect,” says Dr. Yerian. “Building lean capabilities and then teaching others is an excellent development opportunity for our caregivers.”

Hundreds of caregivers from across the organization and beyond have visited decision support services, reinforcing the message that the lean work they were doing was important to future of the organization. The visitors included the Cleveland Clinic’s executive officers, who were all briefed in advance on lean leadership methods, such as productive questions to ask that would support the group’s efforts. They included CEO and President Toby Cosgrove, CFO Steven Glass, and Executive Chief Nursing Officer Kelly Hancock, who returned the following week with her leadership team with the purpose of establishing a similar lean model area in nursing. Today the lean model area in the inpatient nursing unit has achieved dramatic improvements in patient call light responsiveness and nurse communication.

Internal demand ultimately led to the creation of six additional model areas representing a cross section of the organization in both clinical and administrative areas, on the main campus and in regional hospitals. These included: surgical supply, nursing, pharmacy, business intelligence, revenue cycle management (another finance group) and outpatient phlebotomy. After starting with problem-solving tools, each area pulled in capabilities and CI department support as needed. Because they were all following their own path, progress was sometimes painfully slow.

“Just as we ask others to reflect on their work, and where their problems and opportunities are, the CI department had to be doing the same thing,” says Dr. Yerian.

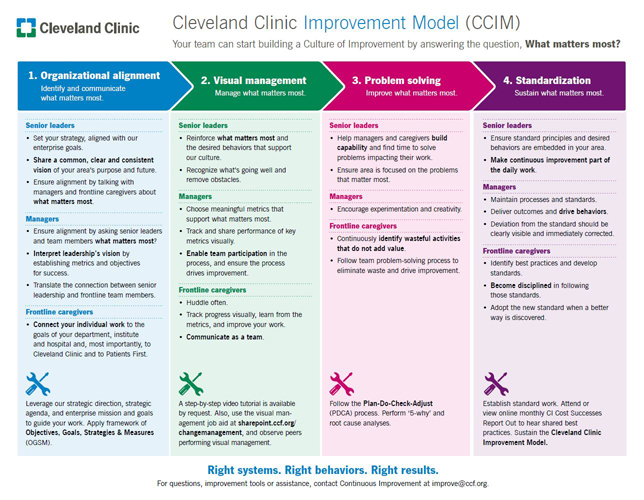

Reflecting on the pace of progress, in the spring of 2014 the CI team began to develop a model for creating a culture of improvement (below). The Cleveland Clinic Improvement Model is based on what was working well in some of the model areas, and the core question: What matters most? It is designed to give everyone a better sense of what they are trying to accomplish.

The CI team defined four key systems and related behaviors that need to be established at each level of the enterprise for the lean management system to be effective. Key elements of the model are:

Today, the CI department members working with each model area are deliberately helping them advance along the dimensions of this framework. The model also provides a common internal language around continuous improvement, supports progress assessments and offers guidance on what managers and teams need to work on next.

CLEVELAND CLINIC IMPROVEMENT MODEL

Accelerating the Cultural Transformation

The seven model areas represent a cross section of the Cleveland Clinic in terms of clinical processes, administrative processes and sophistication. In terms of number of employees directly engaged, the nursing unit model area at one of the Cleveland Clinic’s regional hospitals is the largest with roughly 150 caregivers.

Now that the original hypothesis has been proven, the CI group is working in a variety of model areas and other ways with other departments and areas where managers want their teams to become better at solving problems and delivering on their core purpose.

To reach every employee and drive a lean cultural transformation I don’t think we have to put every single employee through a model area. To get to a tipping point, we have to develop enough capability in enough people and reach enough different parts of the organization.

“To reach every employee and drive a lean cultural transformation I don’t think we have to put every single employee through a model area,” says Dr. Yerian. “To get to a tipping point, we have to develop enough capability in enough people and reach enough different parts of the organization.”

The framework for creating a CI culture could speed up the organization-wide transformation. For example, in recent months when outpatient phlebotomy had a strong mandate to improve performance, the initial impulse was to jump into the traditional project-based approach with the CI department doing some time studies, drawing a process map, and so on.

- Organizational alignment – Does everyone have clarity on what matters most?

- Visual management – Does everyone know how they’re doing in the areas that matter most? Do they know if they are winning or losing today?

- Problem solving – Does the area have an effective way to solve the problems that matter most to the purpose of the organization?

- Standardization – Are the best practices that matter most locked in as a foundation for future improvement? Are the best practices shared with other areas?

But then they looked at all of the variables in the process and realized that volumes and other factors would always be in a state of flux. Caregivers in the area needed to be able to respond to and address any future issues on their own. So instead they started by asking the more basic questions embedded in the cultural transformation model. Does everyone know what matters most to the Cleveland Clinic and what they need to deliver? Does everyone know how they are doing, and if they are winning or losing today?

By starting with those questions, communicating the expectations, and tracking hour-by-hour performance, they made some dramatic improvements in a very short period of time. Specifically, in the six outpatient phlebotomy locations on the main campus, they improved the percentage of patients being seen within 15 minutes from 51% to 96% within two months.

“You need to build the capabilities that will help solve the problems that you face in delivering on your purpose,” explains Dr. Yerian. “In the earlier implementations we were teaching our caregivers some things that weren’t relevant to the immediate problems that they needed to solve. It’s no wonder that this team achieved results three times faster – we eliminated all that waste!”

| ABOUT THE CLEVELAND CLINIC  |

Keep Learning …

- Visit the Cleveland Clinic web page.

- Read the Lean Leadership Series Q&A with Dr. Yerian to get her advice for engaging doctors and senior leaders.

1. “A Collaborative Approach to Lean Laboratory Workstation Design Reduces Wasted Technologist Travel,” Lisa M. Yerian, MD, Joseph A. Seestadt, Erron R. Gomez and Kandice K. Marchant, MD, PhD, American Journal of Clinical Pathology, 138 (2012), 273-280