Be among the first to get the latest insights from LEI’s Lean Product and Process Development (LPPD) thought leaders and practitioners. Subscribe to The Design Brief, LEI’s newsletter devoted to improving organizations’ innovation capability.

In the very early phases of designing the electrically powered Amazon delivery vehicles at Rivian, our designers and engineers spent countless hours closely observing Amazon drivers and other logistics stakeholders as they did their work. We debated observations based on first principles, formed hypotheses, rapidly built many different virtual and physical prototypes, tested them with users, got their feedback, rigorously tested them again, deselected, combined, and eventually converged on solutions. We did all this work before starting to do detailed design because we knew that was how we would create the best possible value.

This anecdote should come as no surprise to practitioners of Lean Product and Process Development. One of the critical findings from my product development research in the late ’90s was that Toyota put far more time and effort into understanding their customer and context at the very beginning of each program than their competitors did. They worked tirelessly to understand and solve the customer’s problem and deliver unique and targeted value with their products.

The other critical difference at Toyota was that a Chief Engineer and a small team of designers and engineers were directly involved in both understanding the customer and executing the program. Having the same people lead both phases of development ensured they would deeply understand what their customers need — and what their product needed to be.

Toyota leveraged the tools and methods of this upfront “kentou,” or study period, effectively. The company created many breakthrough, best-selling products, including the phenomenally successful Lexus brand — much to the chagrin of many “industry experts” who said Toyota could never design a luxury car. My co-author Jeff Liker and I shared many of these stories in the book The Toyota Product Development System. The subsequent rise in popularity of practices such as design and MVP (minimum viable product) thinking serves as testimony to their broad efficacy, ensuring design teams “understand before they execute.”

Closing Critical Knowledge Gaps

But there is much more to the study period than observing your customer. In parallel with deep customer understanding, the team needs to identify and close critical knowledge gaps that stand between their current know-how and what they need to learn to create new value. Whether in engineering, manufacturing, installation, logistics, or service, you must understand how you will deliver unique value.

Set-based experimentation continues to be a powerful tool as you add more workstreams to the process of understanding. Researching broadly, searching for patterns, debating, forming hypotheses, rigorously testing, deselecting and converging across workstreams. Fortunately, a host of digital design and simulation tools are available to enable a more wide-ranging, robust, and faster set-based approach to innovation than ever before.

A final and often overlooked element of the study period is the concept paper, which should continually evolve as your understanding of your customer and your product takes shape. The concept paper is a powerful way to share the product vision, align around a plan to deliver, and enroll the team in the mission. John Drogosz has written more about the concept paper in this month’s “Coaches Corner.”

This month’s video features stories from a wide variety of organizations that have put the principle of “understand before you execute” into practice. Dave Pericak, director of Icons at Ford Motor Company, gives us an insider’s look into the early development stages of the all-new, path-breaking Bronco. Valerie Cole, software architecture manager at Schilling Robotics, a division of TechnipFMC, describes how her team applied this principle to software development on a game-changing, deep-sea remotely operated underwater vehicle (ROV). And the clinical design and innovation team from Michigan Medicine describes how it used these practices to develop clinical processes that led to far better outcomes.

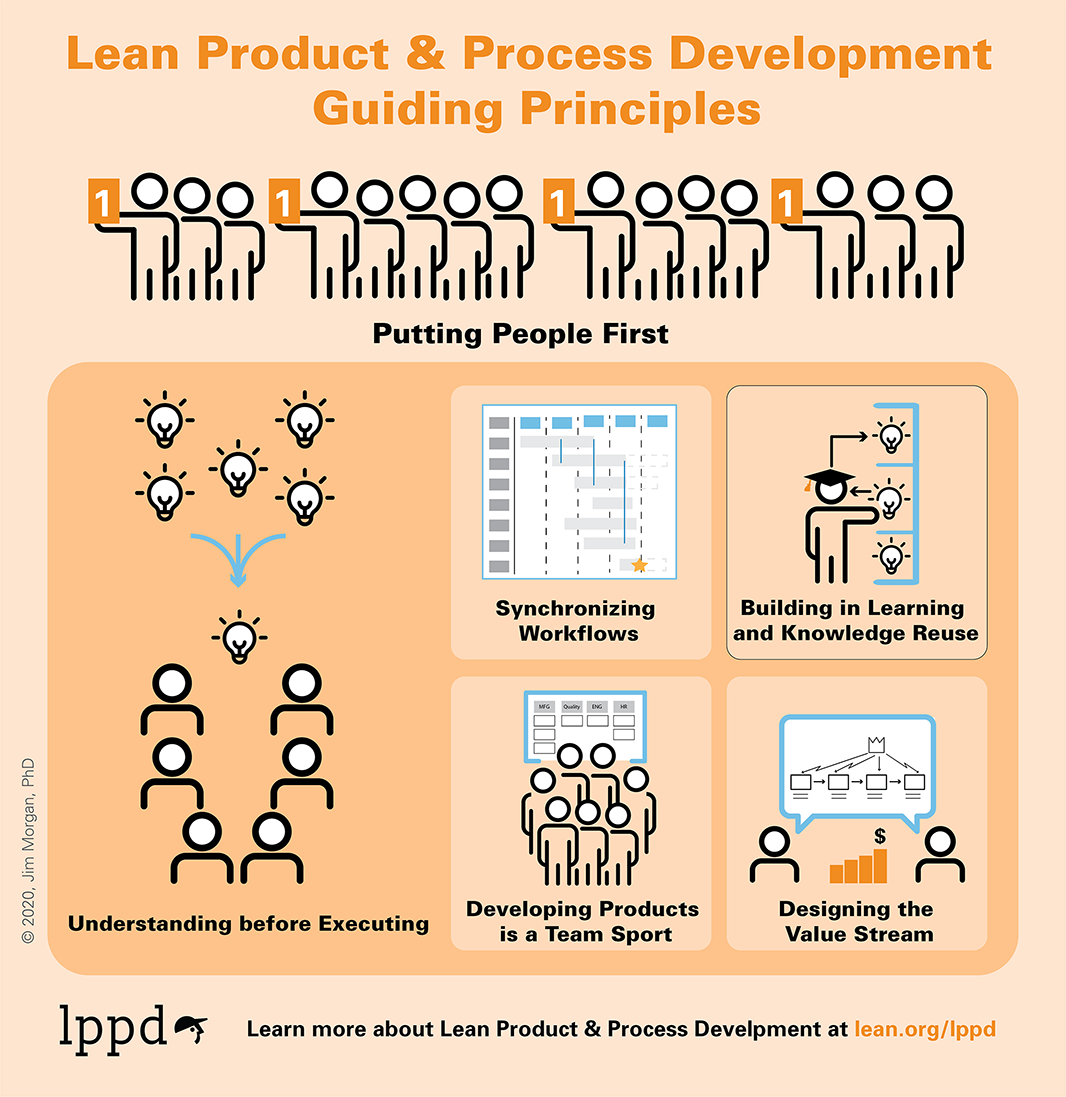

See the Lean Posts and related ebooks detailing other guiding principles:

- Putting People First (coming soon)

- Developing Products is a Team Sport

- Building in Learning and Knowledge Reuse

- Synchronizing Workflows

- Designing Value Streams

Designing the Future

An Introduction to Lean Product and Process Development.