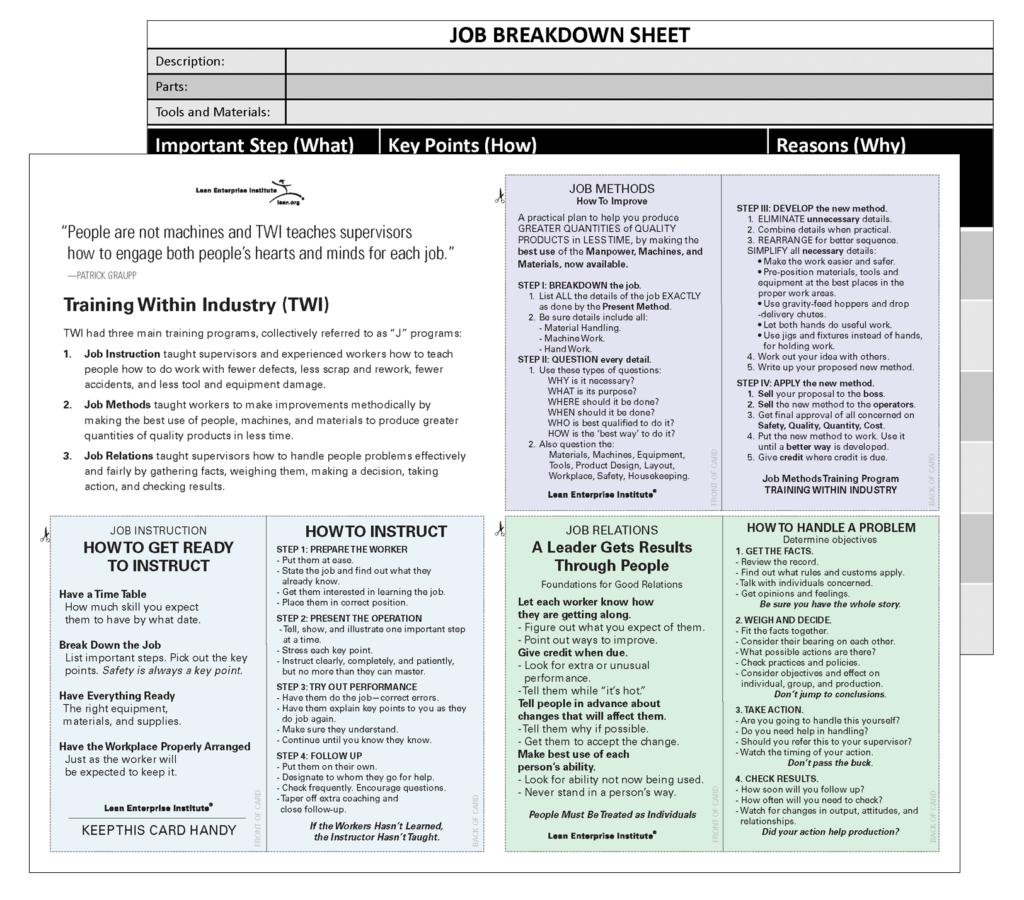

It has been over ten years since I, then a manufacturing engineer, first learned about Training Within Industry (TWI) Job Instruction (JI) from Lean Enterprise Institute coaches. As I now work to help hardware startups develop and optimize their innovative technology and use this method to capture process standards on which clients can iterate, my reflections on it helped me realize how adopting JI not only helps startups build process rigor but also — as importantly — develop a culture of team ownership and continuous improvement.

Early Stage: Building Process Rigor During Technology Development

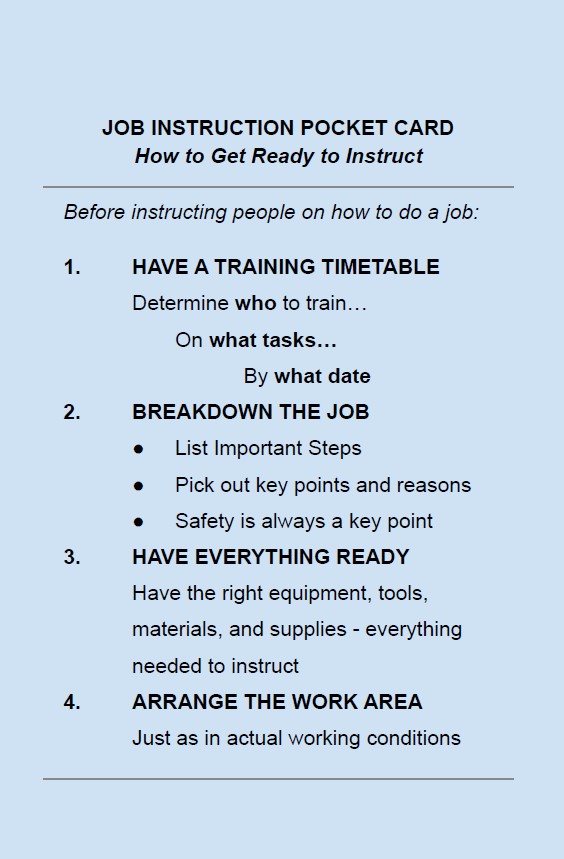

Many early-stage startups operate in a tight-knit, fast-paced environment where multiple process parameters and technique changes happen from one day to the next. In this situation, JI, specifically the Job Breakdown Sheet, is the simplest form of documentation that captures the essential details that may dramatically affect the process output. Formalizing and tracking these details in early process development and maintaining analytic discipline in the plan-do-check-act (PDCA) cycle is crucial — this makes the difference between data-driven and trial-and-error decision-making. Startups doing too much trial-and-error risk wasting precious time and capital and missing performance targets. With JI, teams can stay nimble yet confident that processes remain unchanged despite being performed by different people at different times.

With JI, teams can stay nimble yet confident that processes remain unchanged despite being performed by different people at different times.

For example, a few years ago, while working on functional fibers, my team was optimizing a temperature parameter in a first-of-its-kind process that continuously created thin fibers with microchips embedded inside. We had to get the temperature just right — too high or too low would result in failures. I designed experiments to probe the temperature range, and data collection was quite an effort — it involved testing individual solder bonds between the microchip and wires thinner than the average diameter of human hair. The sample preparation and testing process required extreme care and manual dexterity. To learn and iterate quickly, we needed to enlist the help of our summer intern and technicians, but no one had done anything like this before. However, thanks to Job Instructions, we were able to train them, scale up this testing operation, and generate process insights that informed the next PDCA cycle in a few days.

Late Stage: Strengthening the Improvement Culture

In late-stage startups where companies focus on the consistent execution of the business model, JI is a powerful building block in the company’s pursuit of operational excellence. My experience learning about and using JI in this setting showed me the value of JI from an entirely different perspective.

At the time, the production team had been working to scale up several highly manual, craft-like processes and struggled to achieve consistent quality when one person trained another on the operations. Training could take several weeks for someone to learn the “magic touch” that we couldn’t quite put our fingers on. We also observed that a serial training family tree resembling a game of telephone allowed the process to drift and evolve randomly. The resulting variation manifested in assembly technicians’ different failure rates during in-house testing and field product use.

Over a few months, I observed firsthand the operational and cultural change that took root among the team members.

Over a few months, when the team learned about and worked to implement Job Instruction on critical processes, I observed firsthand the operational and cultural change that took root among the team members. Since then, while leading or supporting training efforts using JI at several different organizations, I’ve repeatedly witnessed its power.

Ironically, when hands-on training is done via JI by default in the organization, it is easy to take the process and the outcome for granted. Therefore, it is important to reflect upon the multifold impact that TWI Job Instruction can have on an improvement-driven organization.

Creating Team Ownership and a Deep Understanding of “Why”

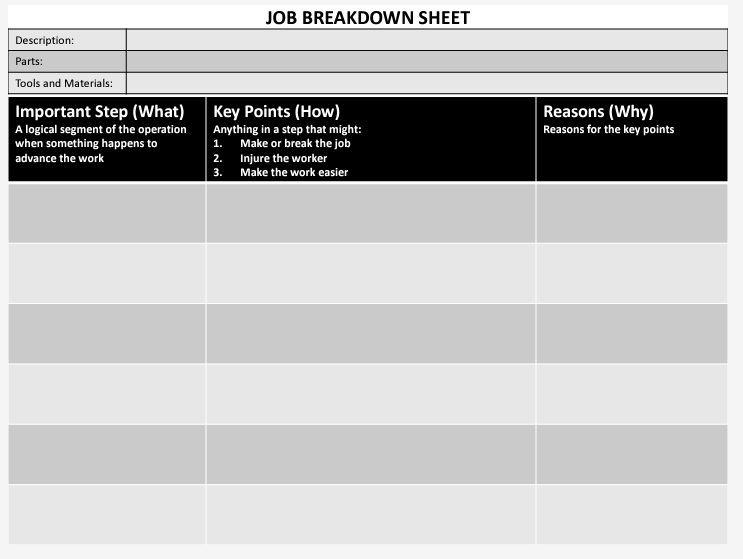

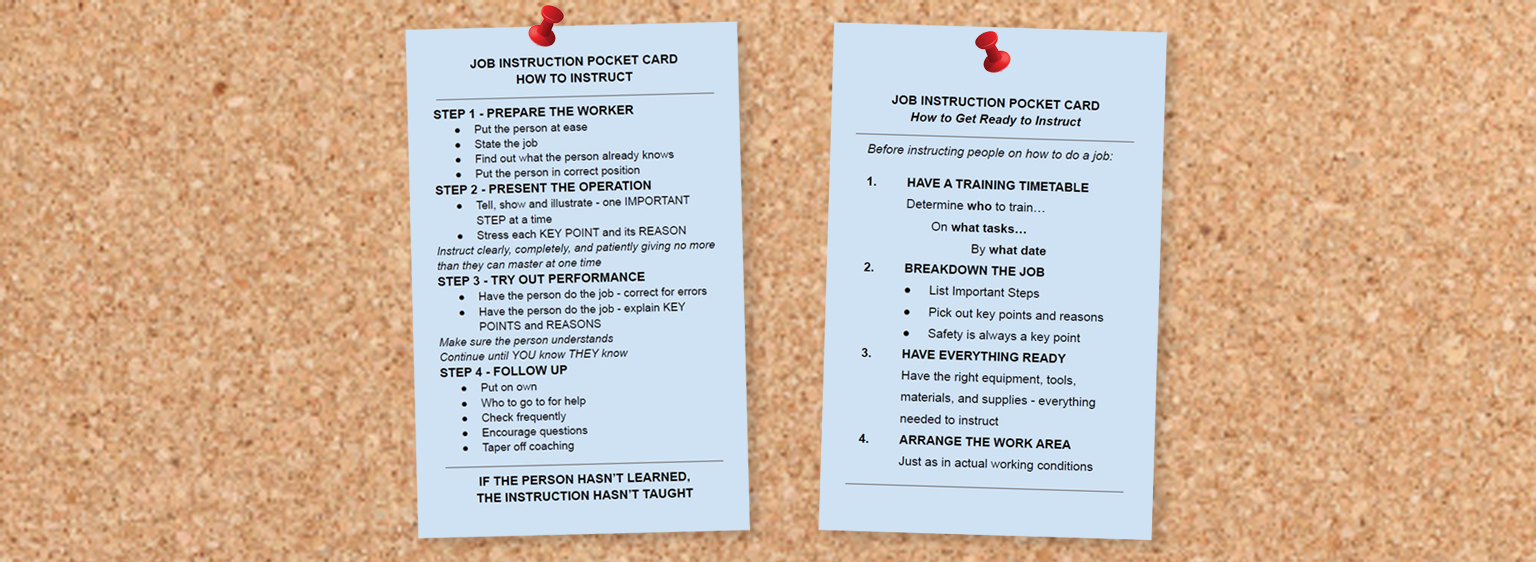

The Job Breakdown Sheet (JBS) is a document that helps the trainer deliver the same information to trainees every time. While preparing the JBS, the team writes down the “important steps,” “key points,” and “reasons.” The need to articulate the key points and reasons concisely forces the team to drill down into the details and determine: 1) what is the “one best way?” and 2) why?

Determining the best verbiage together builds consensus among the technician/trainer, the line manager, and the engineers.

Although seemingly simple, writing the JBS takes practice and iterations to do well. Often, the obvious details are already conveyed to the trainee in the hands-on, non-verbal demonstration of the job. So, this means the “key points” can and should be reserved for subtle details that would truly “make or break” the job. Determining the best verbiage together builds consensus among the technician/trainer, the line manager, and the engineers. Doing this task as a group helps everyone develop a more in-depth understanding and appreciation for the operation. The result is powerful. Once instructions are agreed upon and written down, the know-how is no longer specialist knowledge. Instead, everyone owns it.

With everyone agreeing on the “why,” the team can no longer use the excuses “we do it this way because that’s how we’ve always done it,” or “because the engineer said so.” We consciously and collectively agreed on an explicit “one best way” and have acquired a common language for future iterations. Capturing it on paper not only adds to the organization’s knowledge base but also sets the standard for “see together, learn together” during future improvement efforts.

Shifting From “It’s an Art” to “Everyone Can Do it Well”

Underlying Job Instruction is an implicit assumption that great performance in hands-on jobs can be taught to new trainees rather quickly to achieve the same result. This notion may make some team members nervous, especially those experienced technicians who have intuitively acquired their techniques and “the knack” through trial and error. Without JI, a traditional approach to training would often involve having the trainee shadow and observe the experienced technician or trainer for days or even weeks. The trainee would imitate the trainer, while neither the trainee nor the trainer precisely knows what to emphasize. The results are often not great, and no one knows why.

Job Instruction raises the expectations on the experienced technician/trainer. In one company, we called the experienced technicians “process experts.” The process expert is the only person who can train others in the process they are responsible for. Rather than being the one person with the “special touch” that leads to great results, process experts are tasked with helping all the trainees achieve and perform at the expert’s level. They are also responsible for updating the JBS to implement future improvements.

Training the New Trainers

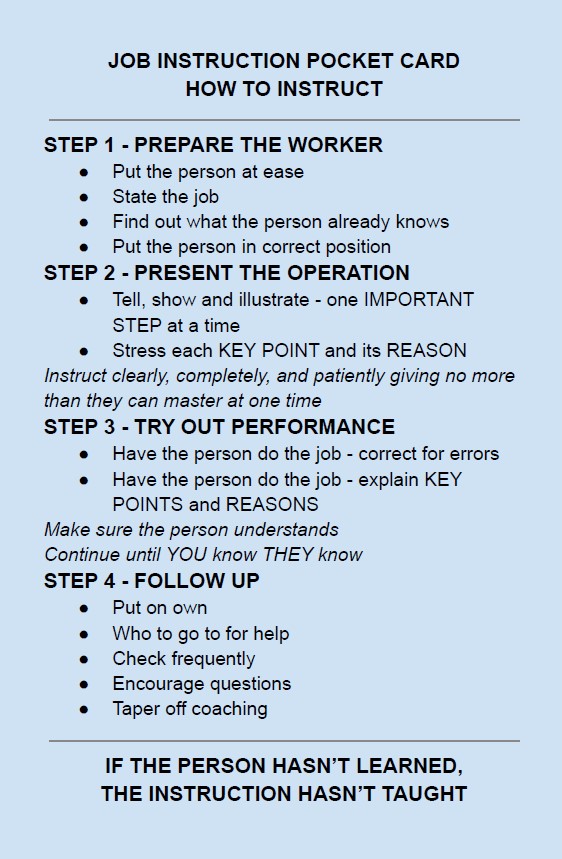

Convincing process experts to take on this new responsibility varied from person to person. I helped process experts practice delivering training according to the “How to Instruct” pocket card. For some, becoming a trainer is natural. Others needed some encouragement and practice to make the transition. Many manufacturing technicians have gotten accustomed to a passive, “just follow instructions and don’t ask questions” mindset from previous work settings. Some were very nervous about public speaking and not confident that they could train their colleagues.

Also, the JI format has its quirks — it took time for people to get comfortable with demonstrating and verbalizing the training content in iterations, each time with an added layer of detail. A few times, the process experts pushed back and jokingly asked, “why don’t you do the training, like before?” It was essential to remind the team that those closest to and most familiar with the work are in the best position to own and improve them.

After the process experts trained someone for the first time, we worked to close any identified gaps before the next iteration. Sometimes we needed to change the wording. Sometimes we needed a few more dry-run practice sessions. For one process, we formalized a test procedure to functionally test a trainee’s assembly before they were officially approved to work on products.

Reflecting on JI’s Benefits

The quantitative gains from TWI JI are significant, but the culture change is priceless. Over time, we shrank training time on complex operations from weeks to days and sometimes hours. The operator-dependent differences in yields decreased and eventually became statistically insignificant.

The quantitative gains from TWI JI are significant, but the culture change is priceless.

However, the most significant change was in how people viewed their work. At first, the change in social dynamics and individual mindsets can be gradual and subtle a, but the long-term difference is impactful and irreversible. The transformation is hard to describe, but I saw the pride in the trainers’ eyes when their trainees did well on a newly learned process, something I’ve never seen before. People also became more open and brought up more problems and ideas to solve them. I could tell they had grown to care deeply about their work — the truly humbling aspect of working on Job Instruction that has stayed with me ever since then. There is not a more powerful example showing how democratizing workplace knowledge can lead to personal transformation and growth.

On a business level, JI enables higher yield, lower COGS, improved product reliability, shorter training time, and higher confidence while scaling up. Startups are in a unique position to leverage JI early in their company’s journey — in addition to the technical rigor it brings process development immediately, JI’s long-term cultural and financial benefits will give companies a significant boost as they transform their innovative vision into impactful, successful products.

Download the Free TWI Reference Guide

Investing in Work(ers) Using Job Methods and Job Instruction

Learn how to develop team members for sustained success.

Great article, this is the foundation for standardize processes and activities that is repeating along the day. The only thing for me is that this needs dedicated people and many of small organizations does not have the economical resources.

Thanks for share

Excellent write-up, Chia-Chun. The article makes a compelling case for TWI in startups. I think it should be stated that TWI not only works effectively for manufacturing, but it also is fully applicable to the service industry (from hospitals to law offices to restaurants) and knowledge creation /sharing organizations (industrial trades schools, agricultural extension, and design offices) as well.

Now my critique of a superficial, narrowly focused, or nominal TWI:

“Training is for dogs. Education is for people…” an old British saying.

Is TWI a part of a company-wide management system such as TPS or equivalent? Or is it an isolated “focused” initiative? Is it done only on the manufacturing floor or there is a clear intention/mandate/vision to do it company-wide through and through (including finance, marketing, logistics, human resources, customer service, etc.) While training and TWI included emphasizes a REPEATABLE AND TEACHABLE set of work instructions, including key points, the ultimate goal is Cultural Change or combined behavior and thinking modification. And it is the JBS, that provides both know-how and know-why, that makes the TWI learning process an EDUCATIONAL ENDEAVOR.

Respect for people is optimized when (a) you are sharing the reasons WHY a key material or procedural detail is important or critical to quality, reliability, or timely completion of the task at hand. Note that rarely people in the trenches of most organizations are told WHY things are to be done this way. They are mostly ordered ‘JUST DO IT”. In this context, everybody, operators, supervisor, engineer, managers, etc are subtly challenged by the JBS … TO IMPROVE or KAIZEN (or innovate with a drastic radical change) considering the sensitivity or vulnerability of the process or product to the particularly challenging key points. In my view, this (engaging in KAIZEN or KAIKAKU) is the max respect for people: “thus far this is the best way we know how and know why to make this product or service, this is our best-proven way now. But knowing your great talents CAN YOU IMPROVE ON IT?”

To sum up, instead of Training Within Industry it should be called: EDUCATION WITHIN BUSINESS (EWB), or Education within Government. (EWG).