In an ideal world, all of our teams would be made up of long-standing subject-matter experts, used to working together collaboratively to deliver solutions and create value for our organizations. But at the company I work for, Telstra (Australia’s leading telecommunications and information services company), perhaps not unlike yours, our teams are often project-based. So we have been focused on finding better ways to explore project scope at the start of a project, when there can be a level of uncertainty and complexity that must be addressed quickly to ensure that we deliver the best outcomes for our organization.

This article is about one of the ways we use the Cynefin Framework to help plan our work in the early stages of a project in order to make better use of the time and the skills of our people.

The Cynefin Framework by Dave Snowden 2014

Cynefin, a framework created by Dave Snowden of Cognitive Edge, is a sense-making tool that people who work in areas as diverse as manufacturing, government, and IT find very useful. It helps us identify the sub-types of work and the practical ways to combine different methods and approaches for effective problem solving and delivery. In essence, it’s a tool used for sensing what type of system we are working in and checking that the approaches we are using are suitable, especially in uncertain and/or complex environments.

I first came across Cynefin while attending CALM Alpha, a Cynefin, Agile, Lean Mashup conference organized by Dave Snowden in the UK early 2012. There I learned how the Cynefin framework helps us understand how Agile and Lean approaches work in each of the four domains and how Cynefin can help tailor team activities to suit.

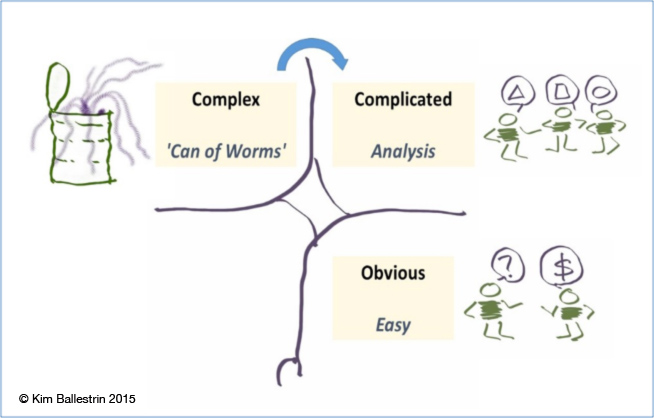

The framework actually has five domains, with the middle zone being called Disorder (in other words, the type of system you’re in before you know what type of system you’re in). The other four domains fall into two broad categories: “ordered” on the right-hand side and “unordered” on the left. Take a look at the image below. It shows three different categories of problems. The categories are based on the Obvious, Complicated, and Complex domains from the Cynefin Framework:

If you have a problem that falls in the Simple or “Obvious” domain, the actions you take can safely be based on best practice because you have a high level of certainty about them – you know what you’re working with. If your problem falls in the Complicated domain, you should to base your actions on expertise and analysis as you still have a high level of certainty and there may be several good solutions available. And lastly, if your problem falls in the Complex domain, you should base your actions on exploration and experimentation. Then you need to identify your assumptions about what’s going on and use specific techniques to look for stable patterns to help you understand what’s really going on.

What you want to avoid with any project or problem situation is applying thinking and actions you’ve used for simple/obvious problems in the past to complex problems based solely on your comfort with a previous process or experience. When you do this, you create more problems, waste time, and almost always get undesirable outcomes.

Using Cynefin for Project Management and Better Decision-Making

At Telstra, we run workshops where we pull together diverse subject matter experts from various functions to provide context and do analysis work collaboratively. Our earliest workshops (Idea Collaboration Sessions) are designed to help us learn more about the customer needs we are trying to design for, the groups and systems we think will be impacted by the project, and the overall costs and time-frames associated with the project. We do this so we can make well-informed decisions about which projects to invest in. We use these workshops to gather the context-relevant information we need to make decisions. They allow us to gain an understanding of the scope of the project and whether it is feasible to deliver it for a desired budget and time-frame.

Once an idea proves feasible, we make a list of high-level functions, features, and capabilities that are required to deliver the project. We make this list by walking through customer experience stories or journeys – the kinds of things you’d recognize from a course on Design Thinking. As we walk through customer journeys, we note any extra capabilities we think will be required to support that customer experience. The principle we use here is to “go very broad and very shallow on scope.” (We may just get out an excel spreadsheet and make a list of required capabilities in column A, see image below).

Next, we narrow the scope to the set of capabilities that we are certain we need to have ready for day 1 (project launch date). This set we colour green in the template, anything that we debate about color yellow, and anything we are sure can wait until a project phase 2, we color white. For the rest of the project we focus only on green items. This saves us time and money by only doing detailed work on the scope we are certain that we need. As we go, we “argue other scope in” because it is more effective to argue scope in after and only after we know what we really need.

At the business case stage of the project delivery process, we are looking to get estimates of the work effort to +/- 30% in order to finalize the business case. Workshops and other activities are focused on defining solutions with these estimates in mind. By asking the question, “How easy is it to estimate this?” we can classify the high-level capabilities, features, or epics into three different types. Here’s where Cynefin becomes useful.

We categorize work items into three types:

- Easy (those that fall into the Simple or Obvious domain)

We can name one person that we can have a 10-20 minute conversation with and he/she can provide an estimate along the lines of, “It will take this long and cost this much” - Analysis (those that fall in the Complicated domain)

There are subject matter experts we can name (or at least the groups that they come from). We are able to plan workshops or analysis activities from 2-3 hours or up to 3 days (any longer is likely to not be analysis). At the end of this time, experts will have come up with a good solution that can then be estimated. - Can of Worms (those that fall into the Complex domain)

These are items we are not sure about or don’t even know who should be involved with yet. Solution options would be heavily debated if we tried to simply workshop them.

|

Features, |

Ease of estimation |

People and groups to involve |

Actions |

|

Work item 1 |

EASY |

Person ‘X’ |

Plan the time to go and ask the person for the estimate, then work the timing in with the rest of the planned activities |

|

Work item 2 |

|

|

|

|

Work item 3 |

|

|

|

|

Work item 4 |

ANALYSIS |

Person ‘A’, Person ‘B’, Group ‘Y’, Group ‘Z’ |

Schedule and plan the workshop and analysis activities based on the people who need to attend. Across the entire scope, itbecomes easy to see which items can have parallel workshops and which need to be done in a sequence given the attendees required |

|

Work item 5 |

CAN OF WORMS |

|

Start by asking questions of yourself and your team like, “What assumptions are we making about this item?” Then use exploratory methods to invalidate or validate those assumptions. DO NOT try to workshop these or combine these items with analysis or easy items. |

© Kim Ballestrin 2015

It can be tricky to work out what to do about “Cans of Worms” projects and problems. A topic or activity that should take just one workshop suddenly turns into three or four. And we end up with a lot of assumption-based conversations. The main thing we want to do is turn these conversations into fact-based discussions. The easiest way to do this is to understand one key assumption and go and find out more information about it.

In one of these projects, we had the product manager go and ask some key questions about another project which was further along and had solved the item that we identified as complex to see if it could be re-used. It took a 30 minute conversation to find out that indeed we could more or less reuse their approach. In this way we avoided derailing other analysis workshops planned for the following week.

Once my team needed to design a solution that we discovered would impact another project no matter how it was designed. People would suggest one thing and immediately the topic would turn to the impact on the other project before we could finish working out a feasible approach to the first one. We went around in circles. In this case we decided to use one session to focus on creating a feasible solution with the attendees from the impacted project (noting the impacts, but not raising them in the session), and another just to discuss the impacts. That’s when I realized we could use the domains in the Cynefin Framework to identify these different kinds of conversations much earlier, which would help us plan our work better. In hindsight, I realized I would have used exploratory conversations or technical “spikes” to check our assumptions first and then run workshops to design the solution with a lot more solid information. So now that’s what I do.

When and How To Use Experts Versus Non-Experts

Back to our ideal world – of course we would like to have “experts” work on all facets of our projects. However, at Telstra this often causes bottlenecks and delays while we wait for a particular subject matter expert to finish one workshop and become available. And there are times when expertise can actually be a disadvantage. In his book Sources of Power: How People Make Decisions, the decision-making research psychologist Gary Klein tells us:

“Expertise can also get us in trouble. It can lead us to view problems in stereotyped ways. The sense of typicality can be so strong that we miss subtle signs of trouble. Or we may know so much that we can explain away those signs, as in the missed diagnosis in example 16.1. In general, these shortcomings seem a small price to pay; however, there may be times when a fresh set of eyes proves helpful.”

We want to involve non-experts in designing experiments as they are likely to explore areas that experts overlook. As Klein says, experts can have a tendency to use familiar solutions and determine that those solutions are appropriate very early on in any process. When work falls into the Complicated domain, this can be effective. But for work that falls into the Complex domain, it is not. It often creates a very inefficient process that leads to long timeframes and large costs.

When we use non-experts, we are able to treat ideas that are proposed to us with a light touch, and use inexpensive ways to test those ideas. The aim is to have many ideas being tested at once and quickly (and safely) learning if they fail or succeed. As we learn more about the items that we are exploring, patterns start to stabilize. Once that happens, the work moves from the Complex domain into Complicated, and the problem situation becomes easier to solve.

In summary:

- When starting a project, find out as early as possible if it is feasible to build a solution for the amount of money and time you are prepared to invest.

- Start with a very broad and very shallow coverage of the scope and then narrow that scope as quickly as possible to avoid wasting effort on further details that may not be required.

- Argue scope in later if needed; don’t try to cover everything and argue scope out later on.

- Pre-classify the types of conversations and workshops that need to happen into a) easy b) analysis and c) cans of worms (if these terms work for you and your organization, or come up with your own for working with the Cynefin Framework)

- And, last but not least, quarantine those cans of worms items! Don’t let them derail the rest of the work you and your team are doing. Then use exploratory techniques to turn the cans of worms assumption-based work into fact-based conversations.