“If you truly believe lean is your operating system, then you don’t stop when a pandemic hits.”

– LEI coach Alice Lee’s respectful challenge to Dr. Kiame Mahaniah, CEO LCHC, March 2020

It is easy to quit thinking and doing lean on any given day but easiest of all when disaster strikes. Who would blame you? As an emergent crisis descends, many organizations activate an incident command center and appoint a leader most suited for the particular disaster. In the case of a global pandemic with many unknowns, healthcare organizations around the world appointed their Chief Medical Officer, a trained physician. At the Lynn Community Health Center (LCHC), the CEO appointed Kimberly Eng, the COO, former chief of staff, and a trained industrial engineer and lean thinking leader. What guided the CEO’s decision?

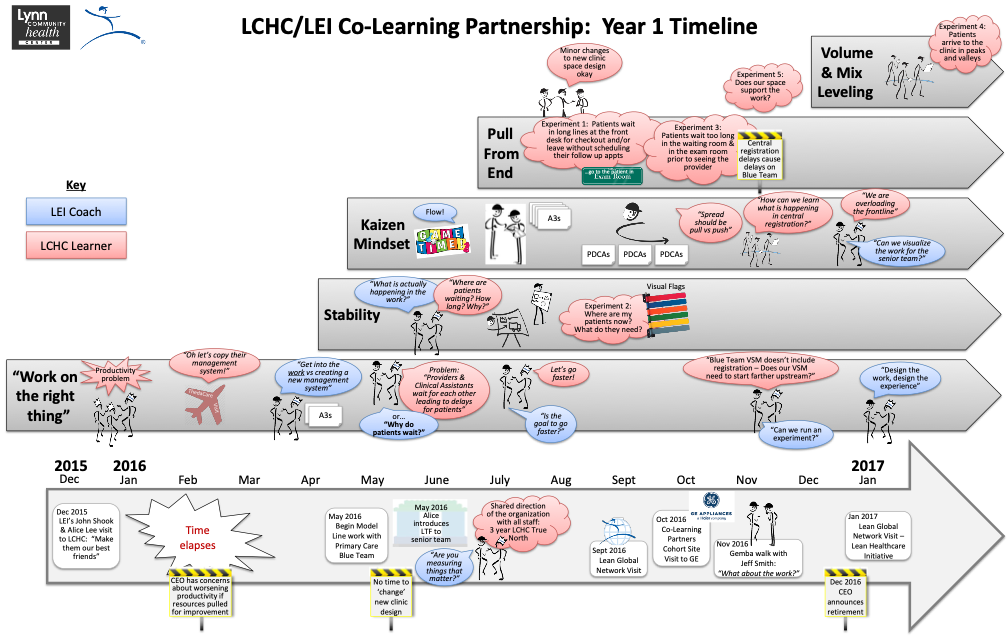

To answer this, we need to go back to 2016 when LCHC confronted its traditional management system with the introduction of a lean model clinic developed by the people who work in the clinic. The dissonance caused by this effort led the organization to begin to shift its long-established mindset and behaviors.

LCHC has been practicing its emergency response in small ways over the past two years ranging from snowstorms to gas leaks. Kim likens this practice to training for a soccer match, where all you can do is practice the fundamentals, plays, runs, and combinations — but when it comes to game day, it’s all about how those pieces come together and how well you adjust to the presenting situation as a team.

A guiding principle for Kim’s thinking over the years has been to think deeply about the next move and its purpose, given the current situation. No formulae, no roadmaps, no copy/paste thinking. A hallmark principled approach that has served LCHC well in the four years of its practice of lean thinking is to start with reducing the chaos and gaining stability. This approach builds a stable platform to make the needed improvements, which often are transformational and enable a significant leap forward.

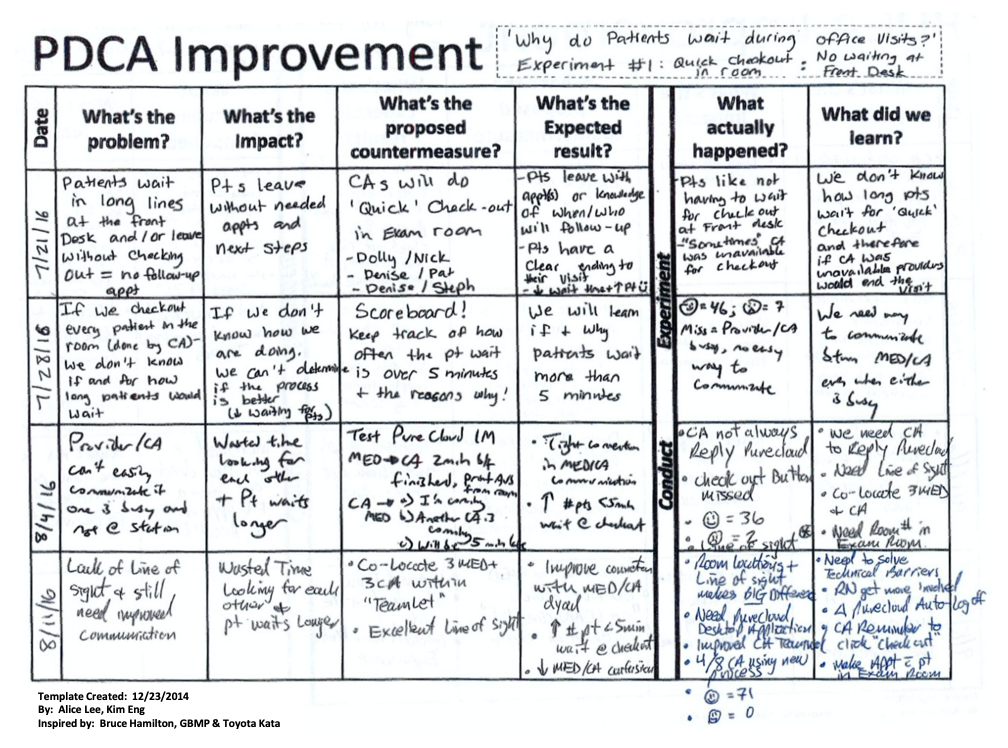

In 2016, Kim’s first move for LCHC (after the leaders toyed with the idea of just copying what they had seen at an exemplar) was to create a model of what a better way could be and reduce the frustrations for both patients and providers. Within a few months of focused effort to reduce chaos and create a reliable and stable work environment, through short weekly tests of change by clinic team members, a model clinic emerged where wait times for patients and providers were essentially eliminated. Kim’s approach was to engage the clinic team to lead the PDCA cycles. Every week, team members documented the problems and their impacts and then crafted an experiment to test their hypotheses on what may best address the issue.

One of the many PDCA sheets that LCHC used to inch its way forward to a model clinic. Click on image for larger version.

As they iterated their way to better and better, investing each week’s discovered knowledge into the next experiment, the team’s problem-solving competence and confidence grew, and keystone habits were formed. This experience created ownership and emotional attachment for the problems and the solving of them by those who do the work under study. There is a human need to co-create experiments and knowledge together, which leads to sustainment and a mindset shift for the team.

The timeline showing the first year of the LCHC-LEI Co-Learning Partnership. Click on image for larger version.

The then CEO, Lori Abrams, was intrigued by the team’s fast progress and asked Kim and the clinic team to take on the design of a new clinic – can we design the patient and staff flows, the information and material flows as well as the physical space to flow at the needs of their patients. Like the model clinic work where a question (Why do patients wait?) informed everything the team did, the team used a question to help the it remain focused with this new challenge, “Does the physical space support the work?” Through the model clinic 3P work, the team had documented standardized work and job breakdown sheets for processes like exam room checkout, rooming, supply kanbans, and visual management flags that pulled people and processes as needed. These standards created a solid foundation to make a more significant improvement leap. With this foundation, the workspace could be designed to support care teams and not functional siloes, offer line-of-sight to the entire value stream, and provide a patient-first perspective. The team completed the new flow design in a few weeks!

Covid-19 Tests the System

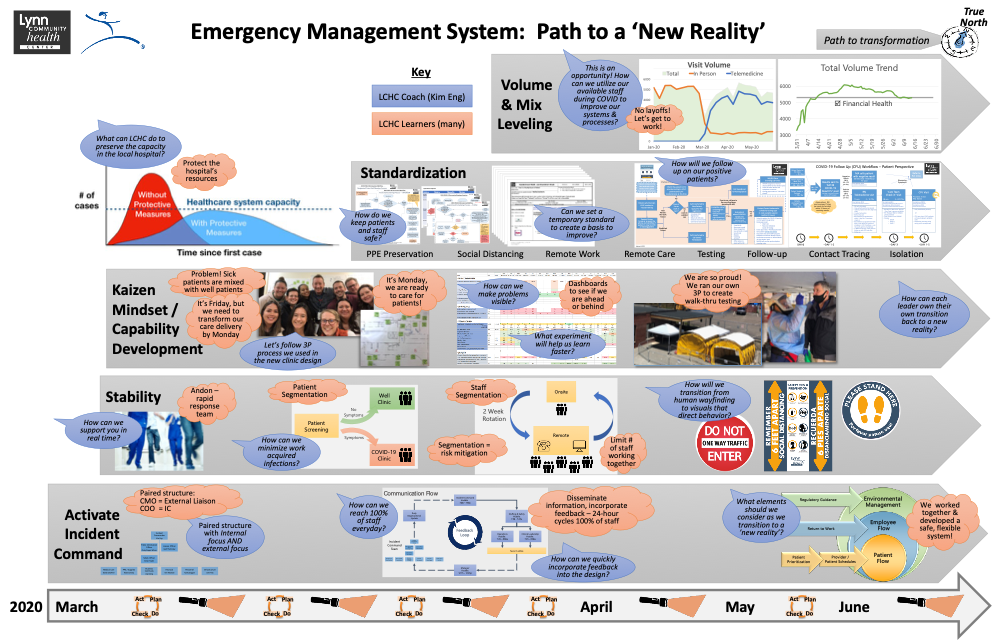

These last four years of thinking and practice to get better and better was put to the test in March 2020 when the pandemic arrived at LCHC’s doorstep. The Covid-19 incident command system was activated, and the CEO appointed COO Kim Eng as incident commander (IC). Kim was paired with the Chief Medical Officer (CMO), Dr. Geoffrey Pechinsky, to eliminate any delays in tackling issues in either clinical or operational realms and to provide an external lens to inform the internal work. As IC, Kim was given the final say and decision-making powers over budget, operational changes, resources, and communication on anything Covid related.

Kim’s first move as IC was to create a management system that allowed for rapid learning and adjustments for this dynamic and unpredictable situation and to keep everyone safe. While other organizations began to furlough and lay off hundreds of their team, LCHC resisted. Kim believed this was an opportunity to leverage their most valuable asset — to entrust their staff to improve and stabilize the evolving work and flows needed to address the challenges presented by the pandemic head-on.

Kim coached the teams to create initial standards where none existed. These were temporary measures to achieve a level of stability and a baseline from where the teams could learn quickly, improve, and ultimately get to even better standards. Amid the chaos, standards (even temporary and imperfect ones) provided structure and meaning. This uncommon approach created teams unafraid to try new ideas because better standards soon replaced old ones in rapid PDCA cycles. The bias for learning quickly resulted in hundreds of new workflows and related job breakdown sheets as LCHC team members redesigned nearly every process and many roles to accommodate the new work requirements of a pandemic.

Kim explained: “Often, we would go live with something as a ‘minimum viable product’ so that we could accelerate our learning process. The situation was rapidly evolving mid-March. The leadership team decided over the weekend we must start screening our employees for symptoms. However, we were days away from implementation. We did not have a documented screening protocol, workflow, or physical flow. Instead of waiting for a full plan, we implemented on Monday with a first draft of a standard. As employees arrived to work, we learned in the moment what worked and what did not, such as how many screeners we needed based on the cycle time. This was a turning point for us as a leadership team – it was a complete mess, but no one was hurt, and we learned so fast (so many problems were uncovered!). We could see how our analysis paralysis often got in our way.”

Measuring Success

In a city with one of the highest Covid infection rates in the state, the LCHC team has been able to design and improve their flows to result in a much safer work environment for their team members. In early March, a staff member was exposed to a Covid-positive patient, which resulted in 17 additional quarantines of staff. Segmentation standards were quickly created to form smaller cohorts of staff to decrease the risk of cross-infection between groups. Work was segmented to in-person care and remote care to reduce the risk for patients while ensuring the health of the business.

The LCHC’s Emergency Management System timeline. Click on image for larger version.

The last three months have demonstrated how one organization with scarce resources can respond to a problem as daunting as a global pandemic using the same know-how and thinking they have practiced to solve many problems over the years. They have learned how to learn, quickly and sometimes clumsily, but learn they did – and continue to do. There is no playbook to follow as the expert advisors for the pandemic are still learning. LCHC has started to create their own playbook, line by line, informed by countless tests of change and failures, starting with keeping patients and staff safe.

“A leader is only as good as her team. I couldn’t be more proud of what the LCHC family has accomplished.”

– Kim Eng, COO & Incident Commander, LCHC LCHC is entering its recovery phase, and the team members are catching their breath from the initial wave of infections. Still, even as the peak subsides, at the same time, they are starting to prepare for the Fall when they expect the next wave of infections. This newly developed muscle of fearless trying to learn quickly — expedited and facilitated by a monumental crisis — is their new way of being. LCHC is ready for whatever comes next.

LCHC CEO Kiame Mahania, MD, and COO Kim Eng will share their lean approach to increasing productivity at LEI’s Virtual Lean Learning Experience (VLX). To learn first-hand from them and other leading lean practitioners, register now.

—

LCHC is located 10 miles from downtown Boston, in the economically, culturally, and socially diverse city of Lynn, MA. As a federally qualified health center, LCHC serves more than 40,000 patients who speak 72 different languages and hail from 113 countries. More than 90% of them live at or below 200% of the federal poverty line. LCHC is a place of hope and love, where caregivers provide long-needed services to a population often maligned and forgotten, where every patient is addressed with terms of respect, and every life is held in the highest regard.