Lean management principles and tools originated on the shop floor to improve manufacturing processes but a regional office of the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has found they are just as effective in improving work flow processes.

The Flight Standards District Office (FSDO) near Boston, while still early in the application of lean principles, cut the time needed to process key certification documents by 51% after using value-stream mapping to find and eliminate delays in the process.

“I wasn’t sure what we were going to get out of it,” said Janet Malouin, manager of the Boston office, referring to the mapping effort. “But I knew that there was a lot of time wasted, a lot of energy wasted, and there had to be something we could do differently.”

The office, one of many regional flight standards offices across the country, is responsible for aviation safety in eastern Massachusetts and all of Rhode Island. The office staff of approximately 30 includes managers, administrative staff, plus safety technicians in three key aviation specialties: operations, maintenance, and avionics.

A FSDO is responsible for implementing safety regulations developed by FAA policy makers in Washington, D.C. FSDOs perform safety inspections, but they must also verify and file the required certification documents for airmen (pilots), flight training schools, repair and maintenance facilities, and companies operating passenger airplanes, helicopters, or agricultural airplanes in the region.

“Anyone who works on anything that has to do with aviation in the U.S. has to obtain certification,” Malouin said.

For instance, if a company wants to repair and maintain a particular type of aircraft, it must document that it has the equipment, manuals, facilities, and trained personnel to perform the work to certification standards. Hard copies of documents and correspondence associated with the application must be kept for various lengths of time (depending on the document) by the FSDO, which also conducts field inspections to verify compliance. The FSDO must also keep copies of numerous documents, including maintenance manuals associated with certifications.

“The FAA office will also continue to surveil you to make sure you maintain the standards, Malouin said. “If you don’t, we’ll issue a violation and/or remedial action.”

At the Boston office, documents are placed in binders kept on shelves in a large library room. Over time, the quantity of paperwork began to overwhelm the existing system, which used two or more binders for each certified operator. One binder contained avionics and maintenance documents; the other, airmen and operation certification information.

“There were a lot of cases where copies of documents had to go into each binder,” Malouin explained. However, documents often were updated only in one binder. Or, if new documentation arrived with a letter from an airline, it could be filed in a correspondence file in the administrative area, not the library. The results were delays for companies seeking certification and frustration for FAA staff trying to find the latest documents.

Then, in late 2007 a pilot project at FAA headquarters in Washington used lean principles to streamline the information flow for updating training handbooks used by inspectors. When the training was made available to the regional FDSOs, Boston jumped at the chance.

Targeting Information Flow

Training at the Boston FSDO began with a half-day lean awareness session for all administrative, technical, and management staff members. A three-day value-stream mapping session followed a few weeks later. The project focus was wide open at the start, according to Cher Nicholas, an FAA Quality Assurance Staff consultant, who conducted the training. “We didn’t know what we were going to look at or what we were going to fix, she said. “It was a busy three days.” There was a lot of discussion and a lot of brainstorming.

“Malouin took herself and the two office supervisors out of the mapping session. “I wanted the people who work where the rubber meets the road to identify the issues,” she explained.

Employees spent day one doing a Pareto Diagram of processes that were not working as well as they wanted. Of eight key processes identified, office information flow was singled out as most important. And the key to improving information flow was improving the system for recording documents in the library.

After the team discussed all the possible projects with Malouin, she gave the green light to improving information flow in the library. “I thought it would give us the most bang for the buck,” she said.

On day two, the team mapped the current state of how documents were processed and filed in the library, identifying 29 incidents of waste such as waiting, overprocessing, and overproduction. On day three, the team created a future state for improving information flow by implementing eight action items.

During the current-state and future-state mapping sessions, the team initially balked at using manufacturing terms, such as “inventory” to identify waste in its office environment. “There was a lot of pushback on the manufacturing terms because they didn’t fit the environment, Nicholas recalled. “We came up with some other terms but interestingly enough by the third day of the workshop, we were using the terms over-production, over-processing, and inventory. These terms still fit because the underlying concepts were the same. All the teams we work with now are very comfortable with the terms.”

After mapping the current state of information flow — how documents came into the process, how they were processed, and how they were delivered to internal and external customers — “it started to become very apparent where in the process improvements could be made,” Nicholas said. “The value stream maps really were a key to helping the team members look together at the whole process to see where they wanted to focus attention.”

The current state value-stream map above shows a five-step process for the flow of information and documents through the Boston FSDO office. A team of 22 employees identified 29 areas for improvement on the map, mostly in the filing/documentation system. The stick-on notes indicate the areas targeted for improvement.

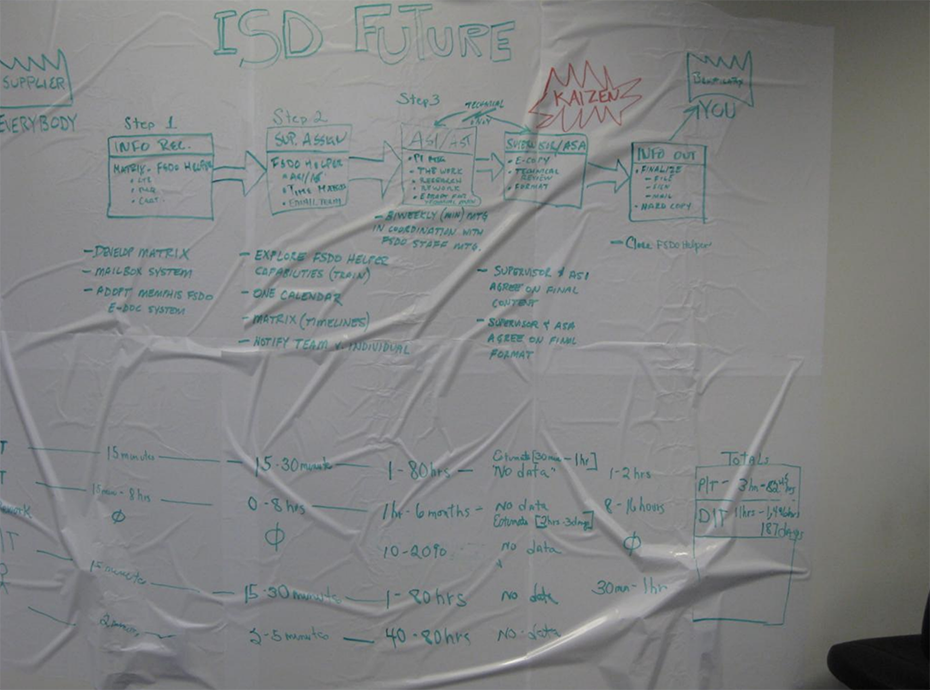

The future state value-stream map below has the same five-step process but now the delays are removed or minimized by creating a streamlined, improved information filing and documentation flow system. Both maps start with “information in” and end with “information out.”

Identifying Root Cause

The overall goal was to make information flow in and out of the library a predictable process. To achieve this, the filing system would have to be improved and standardized to eliminate the causes of delays, duplication of paperwork, and problems with document control.

Many of the wastes indentified by the team stemmed from the traditional system for maintaining paper documents that by law had to be kept on file. (The FAA allows some safety records to be kept on computer files but paper records must be maintained because of the danger that computer files could be lost or wiped out by mistake.) The files contain documents with such information as the planes airlines can operate, what pilots are certified to operate the planes, what flight schools are certified to train the pilots, and what work maintenance or repair facilities are certified to perform. Documents, such as maintenance manuals, also spell out the procedures for doing the work and maintaining certifications. Different operators, such as passenger airlines, agricultural operators, or helicopter lines, require different certifications.

The three departments of safety inspectors — operations, maintenance, and avionics — were assigned to individual airlines or facilities, but documents were kept by department. Because documentation was spread out, an inspector’s task of figuring out if he or she had the most recent document was time consuming. If there were a safety incident, an inspector would have to look in all the books to find legacy information about avionics, maintenance, and operations.

Periodically culling dated information from the files meant searching through two sets of binders.

On December 18, 2008, a week after the mapping workshop, a subgroup of seven people formed the Boston FSDO library core group. They met regularly for the next three months to outline a plan for implementing the eight action items within a year. Basically, the plan defined a way for the three safety departments (operations, maintenance, and avionics) to examine all the documents in their functional binders and condense them into one set that was filed and colorcoded by the type of air operator or facility. The team estimated it would need a year for the project. “It was a huge undertaking,” said Malouin. “This all had to happen while they were doing their regular jobs,” she noted.

Ahead of Schedule

But in October 2009, just nine months later, the team had created a single set of binders that was easy to use and easy to access. Binders were color-coded and organized on library shelves by company type, such as maintenance facility, flight school, air carrier, agricultural aircraft, helicopter service, etc. A template at the front of each binder explained how it was organized, what documents it contained, and how to keep the documentation up to date. All correspondence with airlines and regulated facilities were kept in a separate file. To maintain the new information system, a team of inspectors runs a document retention checklist at least once annually to remove outdated documents. And because all the information is in one binder now, the reviews are much faster than under the old system.

Malouin praised the team effort. “They all got together, they went through the records together, they condensed this massive disaster to one concise book holding everything, and everyone knows where to go to get it.”

Team member Peter O’Leary, principal aviation safety inspector, said the team had an advantage in building and sustaining internal support for the project over the nine months. “I think what helped is that some of us had experience with lean before coming to the FAA. We were able to say that lean does work.” He had used lean concepts while working at United Airlines to improve safety checks.†

Other Benefits

The value-stream mapping project cut the time needed from when a document is received to when it is filed in a binder by 51%. It also virtually eliminated the time staff spent searching for documents and the streamlined filing system helped inspectors learn new assignments faster. But the new system had benefits beyond saving FAA staff and customers time. Having one set of documents contained in one set of binders per company means that every inspector can see the most recent document filed by another inspector.

“It keeps the operations inspectors and the air worthiness inspectors and the avionics inspectors talking to each other, Malouin said. “A huge byproduct of this was the team building. Everybody agreed that this project was needed, everyone bought into it, it became their own, it wasn’t management driven. They took it on and worked it. I made sure they had the resources and got out of the way. I think it also helped people appreciate one another and the value everyone brings to the product.”

O’Leary noted that when people saw that the library project worked, they felt “we can take on other projects.” Subsequent improvement projects that used value-stream mapping included removing delays from a correspondence review process and better tracking and balancing the usage of staff vehicles.

Nicholas said value-stream mapping allowed the Boston FSDO staff to see a process at the same time and work toward agreement on solutions. “They see the opportunity lean provides in helping to find a different way, a better way, for work to flow. By the time we get through the first day of the mapping workshop, they realize lean is a simple but powerful method for improvement. There’s a lot of engagement and by the third day when they do the future-state map, there’s a lot of initiative to deploy it because the process owners create the new process, not me.”

For More Information

Federal Aviation Administration ñ The FAA is responsible for the safety of civil aviation. Established as the Federal Aviation Agency in 1958 by the Federal Aviation Act, the FAA adopted its present name in 1967 when it became a part of the Department of Transportation.

Learning to See Using

Value-Stream Mapping

Develop a blueprint of improvements that will achieve your organization’s strategic objectives.