In order to do more and improve faster, the Cleveland Clinic is rolling out a methodology for building a “culture of improvement” across the 48,000-employee hospital system. Here’s how it works according to the people making the changes.

The results speak for themselves. Expanded capacity, better treatment outcomes, reduced costs, higher morale and a better overall patient experience. Today, lean process improvement methodologies and problem-solving tools have proven their effectiveness in a wide variety of healthcare settings.

The question is not whether the methods for reducing waste and improving workflow pioneered by Toyota can be applied in healthcare. Hospital leaders are now asking: How can we do more? How can we go faster?

In our previous story we shared how the Cleveland Clinic is building upon years of project-focused improvement efforts and striving to create a system-wide culture of improvement in a healthcare system that employs 48,000 caregivers. Their efforts continue to be driven by two primary factors. First and foremost is the never-ending push to improve healthcare quality and treatment outcomes. Second, with the ongoing changes in technology and healthcare reimbursement accompanying the Affordable Care Act, there are so many opportunities for improvement that the only way to succeed is to engage every caregiver every day in improvement rather than relying solely on the hospital system’s CI team.

“We needed to change the culture so that everyone was thinking about it, teach them some basic tools and a basic approach, and drive responsibility for changes to every caregiver,” Robert Wyllie, M.D., Cleveland Clinic’s chief medical operations officer, noted in our previous report.

Using the A3 problem-solving tool, Medical Director of Continuous Improvement Dr. Lisa Yerian and the CI team considered how the organization could build a more widespread culture of improvement. They eventually decided to focus on building caregivers’ problem-solving capabilities, and then provide support for their individual efforts to tackle the issues that mattered most in their areas.

The culture change efforts began in 2013 in Decision Support Services, part of the Clinic’s finance division, which generates the monthly patient care and financial reports that the organization’s managers use to track performance. Using lean tools, following the PDCA process, and modeling lean coaching and leadership practices, the group made and continues to make dramatic improvements. Their ability to sustain and build upon those gains demonstrated changes in mindset and culture that have subsequently been replicated in a number of other “model areas” throughout the organization.

Still, for executive leadership, the questions lingered: How could they do more? How could they go faster?

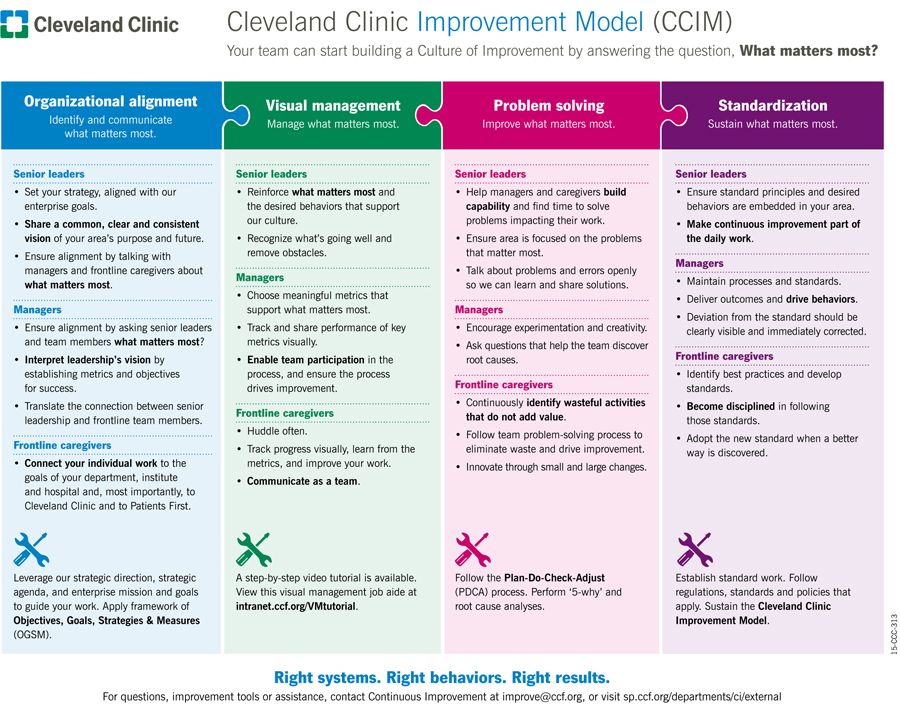

The Cleveland Clinic Improvement Model

To speed up the pace, the Cleveland Clinic CI team developed a model for creating a culture of improvement. The model standardizes the high-level process based on what worked best in the model areas.

Cleveland Clinic leaders and the CI team actively use the four-part model to guide the departments and hospital units on their improvement journeys. To see how it works in practice we went to the hospital floor. Specifically, we visited the medical/surgical nursing unit on the fifth floor of Hillcrest Hospital, one of the healthcare system’s regional hospitals in Cleveland’s eastern suburbs. Following the structure of the improvement model, here’s what we found.

1. Organizational Alignment

As noted above, there’s strong support for the CI department’s efforts to develop a culture of improvement from the Cleveland Clinic’s executive leadership team. Executive Chief Nursing Officer Kelly Hancock in particular was struck by the progress made within Decision Support Services. Early on she visited the area with members of her nursing leadership team with the express purpose of establishing similar areas in nursing.

“Our support has been fantastic from our Nursing Director Sue Sturges and Hillcrest Chief Nursing Officer Sue Collier,” says Matt Drew, nurse manager at 5 Main Tower. “Every time Kelly Hancock has been out here she asks how we can make this move faster throughout the enterprise. That’s why it’s been successful, because we’ve been supported at every level.”

The fifth-floor nursing unit at Hillcrest is one of three designated “ideas to innovation” units. As such it pilots new nursing philosophies, practices, software and technology, which is why nursing leaders chose it to test the CI cultural development approach.

The Cleveland Clinic improvement model repeatedly directs managers to identify and focus their efforts on “what matters most.” The initiative at Hillcrest started by asking the 115 staff members on the unit to do just that by identifying the barriers to providing optimum care.

“One of the top issues was that we were short-staffed,” recalls Drew. “There’s not much we can do about staffing, but we can look at why we are short-staffed. Is it because of people calling off work unexpectedly? Is it because nurses are floating to other units in the hospital? Is it because we have to use our nursing assistants as private sitters” to watch patients.

Patients arrive on the floor, often from the emergency department, before moving to surgery or other treatment areas. In addition to inadequate staffing, some people felt that most patient admissions were always happening at the end of each 12-hour shift. To find out if this was true they started tracking when patients arrived on the unit.

They discovered that, while most patients were not in fact being transferred at the end of a shift, there was a peak admission period. As a direct result of the analysis they realigned nursing resources and created a new shift position from 11:00 a.m. to 11:00 p.m. to better align nursing resources to patient demand.

Matt Drew and his team spent three months tracking responsiveness and staffing, and recording performance data, with coaching support from the CI team. During that period Melissa Vandergriff, CI program director at Hillcrest Hospital, and Susan Coyne, senior continuous improvement specialist within the Clinic’s Nursing Institute, also taught some of the nurses how to analyze this data. They learned, for example, how to create a Pareto graph to plot the root causes of the barriers to optimum care identified by the staff. The barriers and related analysis were posted on the wall of a small, windowless room behind the floor’s main desk. Dubbed the “Improvatorium,” the room is now the nerve center of the unit’s improvement efforts and a showcase for visitors to learn and experience a culture of improvement in the gemba.

Responsiveness was another improvement priority. Specifically, the team tracked how quickly nurses responded when a patient pushed his or her call button. The initial goal was 75% of patient calls answered within 2 minutes, and 95% answered within 4 minutes. Nurse managers graphed and reported the performance for each wing—green if they met the goal, red if they did not—which all caregivers could see during the huddles at each shift change.

“The majority of our sheets were red to start with,” recalls Coyne. “Making their performance visible, making everyone aware of the metric and how they were performing helped the team slowly start to turn them green.”

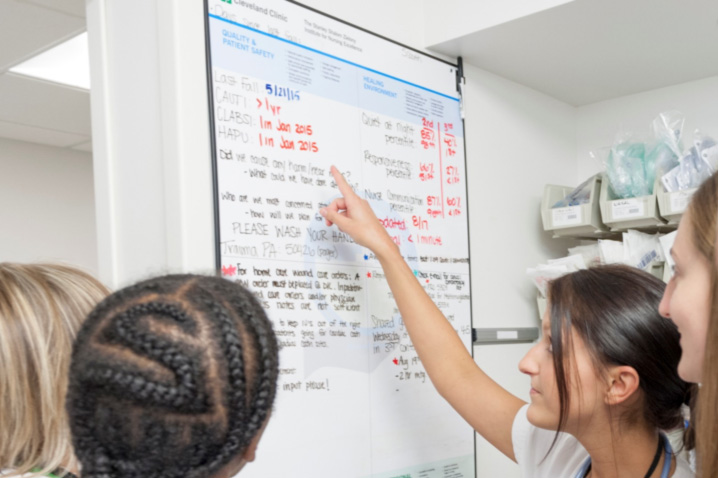

Tracked through the call light system, responsiveness is now one of several key metrics updated and reviewed on a weekly basis. The metrics are reported on white boards that the Cleveland Clinic installed several years ago throughout the healthcare system. These white boards outline a “professional practice model” (PPM) for nursing. The unit at Hillcrest studied and refined how they use these PPM boards, which we’ll present in more detail below. Caregivers huddle around the boards twice a day at the change of each shift.

“We defined standard work on how the board is updated, what it includes, where the data comes from, and who updates it,” says Drew. “That way we make sure that we’re consistently getting that information out to everyone.”

In addition to how to use a daily performance board, unit staff members learned about other visual management tools through an online internal training video. Another video, which the caregivers viewed as their schedule allowed, taught them how to identify the eight forms of waste.

After watching the eight wastes online video, managers asked everyone to record the waste they encountered in their everyday work. A classic example of “be careful what you wish for,” when those lists were turned in managers quickly realized both how much work they needed to do, and that they needed an effective way to prioritize all of the ideas. The online videos and visual tools enabled caregivers across multiple shifts to participate in the changes because they could engage at any time.

3. Problem Solving

On a day-to-day level nursing is legendary for creating workarounds in order to do what’s best for patients. The problem with such individual initiative, absent a formal problem-solving methodology, is that the underlying causes of the issues are never fully addressed and keep popping up.

“As a caregiver, when we have an issue we jump right in to fix it. That’s our nature. That’s how we’re trained,” says Coyne, who worked as a nurse and nurse manager for 22 years prior to joining the CI team. “We need to take a step back and ask, ‘Why?’ That’s how we get to the root cause and make sure we’re fixing the right things. As an improvement professional supporting the Nursing Institute, my biggest challenge is getting people to slow down.”

Creating an A3 report improves the problem solving process by documenting the current condition, getting everyone to agree on a target state, analyzing what’s going wrong, determining root causes, developing potential countermeasures and building consensus around a correction plan. The first A3 created by the Hillcrest nursing unit tackled their patient responsiveness challenge. After asking everyone to identify everything that was preventing them from being more responsive, and digging down into the root causes, managers asked all 115 caregivers to help come up with countermeasures.

“We received roughly 240 countermeasures that we then went through,” recalls Drew. “We looked at what would work, what wouldn’t, and what could be blended together. Then we went back to staff and presented what we thought we could do.

“The powerful thing about this process is that it isn’t only about solving the problem. It’s about shifting the culture from one where people are mandated to do things, to one where making change is embraced. We try new things and see if they work,” he adds. Because the responsiveness countermeasures were fairly extensive, and the unit operates 24/7, the frontline staff led a number of training sessions introducing the changes. The countermeasures that they introduced included new standards for:

- Making and tracking nursing assignments

- Conducting the daily huddles in preparation for new admissions

- Welcoming newly admitted patients to the floor

- Eliminating a step where call lights were routed to caregivers by fully utilizing the features of the current technology

- Performing leader rounds to ensure all patient needs have been addressed.

The powerful thing about this process is that it isn’t only about solving the problem. It’s about shifting the culture …

They launched these countermeasures in tiers over the course of a month. The results were striking. HCAHP responsiveness domain scores jumped from a monthly average in the 4th percentile to the 50th percentile or higher each month. The unit’s average response time dropped 23% from 1:38 minutes to 1:15 minutes, which contributed to a 24% reduction in patient falls from 2014 to 2015.

Building on the success of the unit’s efforts to improve responsiveness, managers handled the staff’s waste reduction ideas a bit differently. On one wall of the improvement room they created a “kaizen board” where they post the ideas submitted by caregivers on individual cards.

As with the PPM boards, they leveraged an existing management process to prioritize, implement and track the ideas. Nursing units at the Cleveland Clinic use a “shared governance” model to solicit ideas for improving patient care, the work environment, job satisfaction and retention. The medical/surgical unit at Hillcrest has a two-hour shared governance meeting on the third Wednesday of every month, which everyone is welcome to attend.

“That’s when we discuss what’s happening on our floor,” says Krissy Cochrane, assistant nurse manager, 5 Main Tower. “We talk about making changes to benefit our patients and caregivers, and generally how to make the floor a better place. Before we started the lean process, ideas would only come in from people who could attend the meeting. Now, the kaizen board is our platform for discussion. We spend the second hour of our shared governance meeting in that room, talking about where the ideas are in the implementation process.”

The shared governance co-chairs review and approve all ideas. When we visited so many ideas had been submitted that a fair number were on hold. Initially, the nurses and other caregivers who came up with the ideas worked on them with the assistance of a coach from the CI department. Today, the unit’s nurse manager and other team members provide that coaching as needed.

“When an idea is approved, we provide the caregivers with a coach, and empower them to work on the ideas. They then bring their countermeasures back to shared governance, where we discuss it, standardize it, and it becomes our future state,” Cochrane adds.

Each Cleveland Clinic hospital has a monthly meeting when the shared governance leaders for each unit come together and work on projects that impact the hospital as a whole. As Susan Coyne explains, “Shared governance gives caregivers a voice to address problems. The problem with it was that we hadn’t really taught them how to problem solve. We’re utilizing the lean methodology to teach every caregiver better ways to do that.”

I was worried at first, when we first started getting positive results, how we were going to sustain it?

The problem-solving training includes creating and using process maps, fishbone diagrams, affinity sorts, Pareto graphs, SIPOC, and other process analysis and improvement tools. It never stops. Once people have been trained on the tools and process, they are expected to teach and coach others. This “multiplier effect” is central to the Cleveland Clinic’s improvement strategy. Building such capabilities makes every caregiver a more effective problem solver, accelerating the organization’s progress and deepening the culture of improvement.

“This is the way we solve problems today,” says Matt Drew. “Yes, I have to be reminded of that sometimes. Most people become managers because they can solve problems. If someone comes to me with a patient safety or quality issue, I will decide what we need to do. Other than that, they fill out a kaizen card and we’ll put it on the wall and figure out what to do. It’s about moving from a rescuer to a coaching manager role.”

4. Standardization

The fourth element of the Cleveland Clinic Improvement Model is standardization. The purpose of standardization is both quality—ensuring that everyone follows the practices determined to deliver the best treatment outcomes—and providing a solid foundation for future improvement.

“I was worried at first, when we first started getting positive results, how we were going to sustain it. But because we took our time, and we identified root causes, sustainment has been relatively easy,” says Drew.

Although no day in nursing is ever standard, the unit maintains a number of standard operating procedures (SOPs). For example, they have an SOP for how they welcome new patients to the floor. The standard is based on what has collectively worked best in the past, with clear checks and balances.

In the CI room there’s a standard work wall where the SOPs and process maps are posted. They review the SOPs during new employee orientations, and managers conduct regular audits to see if the processes are being followed and working effectively.

“Generally, the staff let me know if a process is broken,” says Drew. “We’re not great 100% of the time, but we’re better than we used to be. That’s what improvement is all about. We’re better than we were, and we’ll get to great later.”

A year and a half ago, the floor was down and out … this whole effort has created a total 180-degree change.

Effective visual management tools indicate when there’s any deviation from the standard process or targeted performance. The medical/surgical unit’s PPM boards support sustainment in several ways. Developed by the Clinic’s nursing leaders, the boards communicate “what matters most” to an effective nursing practice at the Cleveland Clinic: (1) quality and patient safety, (2) creating a healing environment, (3) research-based practices, and ( 4) education. The appropriate metrics and related information—response times, patient experience scores, shared governance meeting times, etc.—are reported in each quadrant.

“When we first started our lean work, we didn’t use the PPM boards the way they were intended to be used by the Nursing Institute,” says Krissy Cochrane. “We had a lot of patient-specific things on there. Through this process we made a new patient status board. The off-going wing charge nurse leads the shift-change huddles around these two boards. They share how their shift went, what to expect, and which patients we need to be worried about.”

Signs of Culture Change

By addressing the root causes of issues, making clear performance improvements, and sustaining their progress, the culture on the medical/surgical unit has changed dramatically in a short period of time.

“A year and a half ago, the floor was down and out,” recalls Cochrane. “We had a lot of people leave at one time. Staffing wasn’t very good, and everyone was burnt out and overwhelmed. This whole effort has created a total 180-degree change. It’s a nice place to work now. I’ve seen so much positive change.”

Employee turnover, a frequent gauge of the culture and the work environment, is actually up. But that’s the nature of a medical/surgical floor, according to Drew. They welcome many new graduates who start here to get solid nursing experience before moving on to critical care or the OR. Since the changes, the negative impact of personnel changes is much less of an issue, he adds. When new nurses are introduced to the floor, they are introduced to the problem solving methodology.

“As a manager on the floor, the biggest benefit of these changes has been the culture shift,” he says. “The staff is now a catalyst for change. If a proposal won’t lead to poor quality, or put a patient or co-worker at risk, the attitude is, ‘Let’s try it.’ If we fail, we’ve learned what doesn’t work and we can move on. That’s the PDCA cycle.”

As an example, Matt Drew relates the story of a recent update to the patient call light notification process. Of course the technology worked perfectly during the trials and the rollout on the day shift the first day. But the nightshift ran into some major issues. Rather than pushing to return to the old system, as they might have in the past, the nightshift staff outlined everything that wasn’t working, why it wasn’t working, and how it needed to be fixed.

When something isn’t working in a hospital, the cause can often be traced to other departments. At Hillcrest, when a card goes up on the kaizen board, the frontline staff are empowered and increasingly comfortable reaching out to facilities, or IT, or clinical engineering, to talk about what’s wrong with a process. They’ll even visit the other departments to better understand what’s going on.

This “going to the gemba” approach to problem solving breaks down barriers between departments, fosters teamwork, and focuses everyone on fixing the problem, not assigning blame. It’s another key element in building a culture of improvement in a large healthcare organization like the Cleveland Clinic that is enabling them to do more and move forward faster.

“When we first started, we thought that we would have a lot of barriers,” Krissy Cochrane concludes. “But through this process, working with other departments throughout the hospital, and with the support of leadership, we’ve really removed a lot of the barriers to change things in a positive way.”

Keep Learning:

- Read the first case study: Transforming Healthcare: What Matters Most? How the Cleveland Clinic Is Cultivating a Problem-Solving Mindset and Building a Culture of Improvement.

- Read the Lean Leadership Series Q&A with Dr. Yerian to get her advice for engaging doctors and senior leaders.

- Meet the nurses on this unit and visit the “Improvatorium” (Cleveland Clinic video) to learn more about how the Cleveland Clinic is building a culture of improvement.