Zingerman’s has been growing and evolving since the first delicatessen opened nearly four decades ago in Ann Arbor, MI. Over the years, the company has grown into a collection of retailers, wholesalers, producers, and distributors called Zingerman’s Community of Businesses, each with its own specialty.

Zingerman’s Mail Order, an online grocery and gift store, is one business that’s had to adapt, perhaps more than any, amid the Covid-19 pandemic. Demand has increased more than 40% since the pandemic began, says Teri Laeder Zingerman’s process engineer.

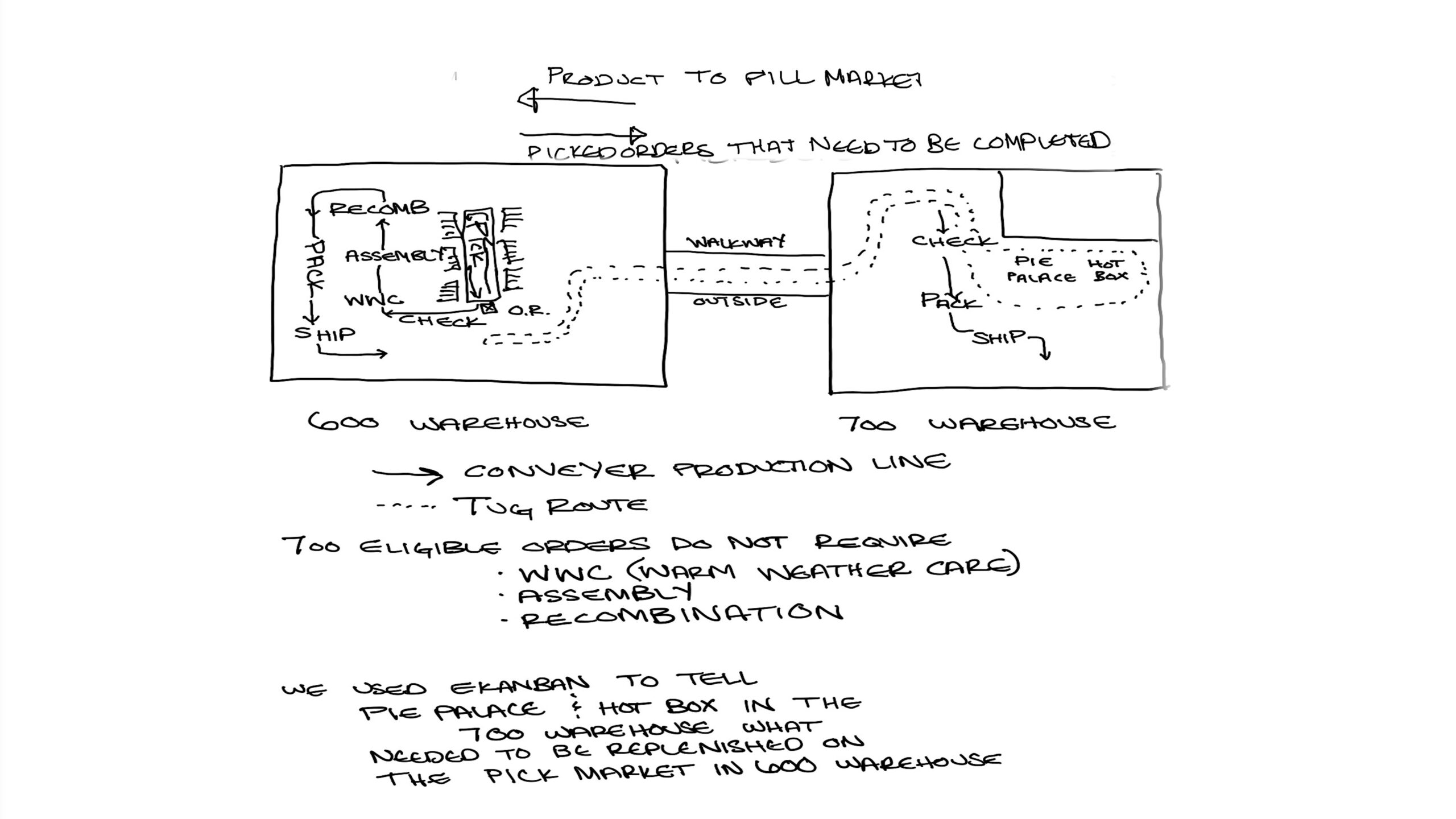

To keep pace with the demand spike, Zingerman’s applied lean principles that the business unit has been practicing for approximately 15 years. Among the changes was the development of a second production line in a warehouse across the street, which receives work orders through an e-Kanban. Additionally, the products from this secondary line move to the original line, where they are packed for shipping via electric tugs. This system also relays information to the line operators through various visual signals. For example, electronic monitors at each work cell display the customer orders, and the tug is sized to hold only 30 minutes of inventory.

This visual-management system provides more visibility into demand and inventory needs, which is critical in a business that deals with perishable goods and fast turnaround times. Combined with the tug route, the visual system allows the team to add capacity and efficiently move products without compromising safety by overcrowding workers in a single facility, Laeder says.

“It allowed us to have 130 people in our main warehouse, and then an additional 30 people per shift working in this additional space (to meet demand while maintaining proper social distancing),” she explains.

Zingerman’s Lean Journey

Zingerman’s Mail Order began its lean journey when Jeffrey Liker, professor of industrial and operations engineering at the University of Michigan and author of The Toyota Way, introduced one of his PhD students to the company. The student, Eduardo Lander, and Zingerman’s Mail Order Managing Partner Tom Root ran several experiments with the help of an engaged team that helped set the tone for a transformative journey.

One experiment involved the creation of lineside markets to facilitate a build-to-order model for the company’s popular Weekender baskets to replace the previous method of batch production. In the past, the company would assemble the gift baskets on a long table, and workers would pull items, such as a loaf of bread or a brownie, from racks and package each item in boxes and store them in different locations throughout the warehouse, Root explains.

6 Guidelines for Monitoring Visual Management Systems

Zingerman’s Mail Order uses six rules to help it evaluate the system’s health.

- Customer Process withdraws items in the exact quantities specified on the kanban (visual queue).

- Supplier Process produces items in the precise amounts and sequence specified by kanban.

- No items are made or moved without a kanban.

- A kanban should always accompany each item.

- Defects and incorrect quantities are never sent to the downstream process.

- The number of kanban is reduced carefully to lower inventory and to reveal problems

“What that meant is that as the night went on, the amount of completed gift boxes began to grow and grow, and this was the source of that space problem,” Root says. “So here we have these boxes everywhere.”

To move toward a build-to-order model, the Zingerman’s team created inventory racks with rows of food where workers could pick the ingredients. Next, the worker builds each box by gathering ingredients from the marketplace and then sends it down the line for final packaging and shipping.

“The quality of the basket went up because the maker was focused on one at a time, so they were better built,” Root says. “The accuracy of the contents of the basket went up. … We had a very early win. It felt like a big success in terms of quality, and it was apparent it was going to solve that space problem.”

This earlier lean work provided the foundation the company needed to contend with extreme fluctuations in demand and the need to incorporate new social distancing and safety protocols when the pandemic hit. So, Laeder, Root, and the team reached into their problem-solving experience grounded in lean thinking.

Leaning on Experience

The pandemic left the team with a short window of time to prepare for the unexpected demand spike and a huge challenge in maintaining flow. Creating continuous flow means producing and moving one item at a time or in small, consistent batches through a series of steps as continuously as possible. Ideally, the flow would match the customer-demand rate, each step making just what is needed by the next step. To achieve this, the Zingerman’s Mail Order team first resized various lineside markets based on demand.

Then, the team members needed to figure out how to incorporate additional space to ensure proper distancing and limit the number of people in one area at any given time. Finally, they decided to add the second production line at a newly built warehouse across the parking lot from its primary operations and link the two facilities through the tug system inspired by its existing pull production process. Laeder and her team also created an electric signal, an e-Kanban, that tells operators what to produce and when to replenish the market.

The Zingerman’s Mail Order Tug Route

The ordering system electronically transmits the information about the products, including location and quantity, required to fill each order to the appropriate location on the production line, where the operator views it on an electronic display. In turn, the operator picks the product, attaches a sticker printout of the product, and adds it to a tote attached to a tug, which travels to replenish the lineside market, where other operators — who have the order printout — add other products to fulfill that order. Once the order is complete, the tug delivers it to the packing and shipping work cell.

The printing of the work order triggers an e-Kanban signal at the work cells in the packaging warehouse, notifying them what to build. The e-Kanban is essential because the assembly team works in a separate warehouse. The only other option was to place color-coded flags on the carts to signal the next order, but that would have added 30 minutes to the production process, Laeder says.

In addition, certain items, such as chocolate, are not eligible to be placed on the trolley because they’re temperature sensitive and need to be packed with ice. So, the team included a visual signal on the work order to notify workers which products they could place on the trolley for final packaging.

When the size of the markets shifted due to the pandemic, the team added kanban signals. The number of Kanban signals represents the number of inventory items the customer needs and the time to complete the route. This visual system enabled the team to see and understand they would not run out and, at the same time, not over-produce.

Change for the Better

The kanban system provides everyone with the information needed to stay on the same page. Managers can focus on problem-solving and meeting customers’ needs instead of relaying instructions to the workforce. The process enables more visibility into production rates versus demand, inventory levels, and any issues encountered along the way. And each team member in the process has the visual tools needed to make adjustments based on demand. The team can see and solve problems quickly before they get out of control, enabling flexibility when fluctuating demands are ruling the day.

The system also provides an efficient way to meet customer expectations without sacrificing employee safety or product quality during this challenging time. Looking ahead, the team is looking to improve its e-kanban app, so it can match to demand.

“We created all of this in 100 days, so we created the bare-bones skeleton of how we wanted this application to work, so we’re making it cleaner and testing it to make sure it’s doing what we want it to do, Laeder says.

You can learn more about the Zingerman’s Mail Order journey in the graphic novel Lean in a High-Variability Business by Eduardo Lander, Jeffrey K Liker, and Tom Root.

Read other recent Lean ‘n Food Posts:

- Transforming a Food Desert to a Food Oasis–During a Pandemic

- Reach for Your Mind Before Your Wallet

- Rethinking the Retail Food Industry

- Planning the Purposeful Turnaround

- Reimagining an Industry in Crisis

Meet Karen Gaudet, one of several LEI lean coaches who stands ready to design an education and coaching program that meets your needs precisely. With our customized coaching and learning experiences, an LEI coach will guide your team through the practical application of lean principles and practices, helping them learn as they address a real and meaningful business objective. Schedule time today to talk with a lean coach.

Meet Karen Gaudet, one of several LEI lean coaches who stands ready to design an education and coaching program that meets your needs precisely. With our customized coaching and learning experiences, an LEI coach will guide your team through the practical application of lean principles and practices, helping them learn as they address a real and meaningful business objective. Schedule time today to talk with a lean coach.

Or learn more and register for LEI’s new workshop, Learning to See Using Value Stream Mapping, a go-at-your-own-pace, web-based course based on the innovative information in the landmark Learning to See workbook, which introduced value-stream mapping to the world.