“I can’t see it,” my boss and mentor announced to my team and me.

10 of us had gathered around from all areas of a heavy industry and technology intensive operation, having just shared the results of a 3 month intensive quality improvement project we’d been working on. Anything, I mean anything, but that comment, I thought. To me, this was the equivalent of cleaning your room to a spotless condition and having your mom declare it “a good starting point.” Only this was worse, much worse. A lot of people had invested many hours of human power (hand and brain) to make an impressive reduction in the act of passing a defect from one process to the next. Call it quality improvement, a morale builder, cost avoidance, scrap reduction—just not “invisible.”

In my world at Toyota, this didn’t make my boss a jerk; it meant that my team and I had some serious reflection ahead. After picking my team up off the floor, I had a “lunch and learn” with my boss/mentor to discuss. Let’s call him Mike.

“So, what’s the deal? Was it really that bad?” I asked.

“Of course not,” he said, “but you know the Improvement Story is critical for people to be able to see the importance of what they have done and for others to want to be involved in the future. The others on the team need to hear that critique and know that it isn’t enough to make real improvement. Without connecting the hands-on work to a clear business need people feel, this work won’t have meaning to anyone beyond this team.”

“Okay, I know the Improvement Story is critical,” I heard myself appealing, “but it’s like we have to do two almost impossible things. 1) we have to make a good match of improvement strategy to the skill of the team. And 2) we have to develop their capability to tell a visual story of what we did, of things that are virtually invisible.”

He smiled at me and said, “Yes, it is exactly like that.”

As we worked through the details of what was missing, it struck me that I hadn’t coached my team explicitly on how to visualize our work. Why was that, anyway? I realized that making a good visual story of improvement work is not something most people want to do or know how to do.

“And why is that?” Mike asked.

“Fear, I think. Different things for different people. But we don’t have a lot of experience with visualizing work, so there is just a fear of looking stupid in front of others. We may be kaizen literate, but not visually literate.”

He agreed, and so we spent the rest of our time discussing how to clarify what visual literacy means in the continuous improvement world, and how to develop those skills.

Years later, I’m still on a quest of how to develop these skills—in myself and others. The definition of visual literacy still isn’t clear in the lean community. There are many ideas and opinions. Most people think of this as some combination of visualizing Big Data, graphic design techniques, and visually-facilitated strategy sessions. I think of visual literacy more as “Cognitive Visualization,” as referenced by David Sibbet in his book, Visual Leaders. This concept includes things that help us visually make sense of our world such as mental models, frameworks, and personal visions that guide and shape our behavior. This is something I’m passionate about because having skills to visually show the way things work and the impact that has at many levels of an organization in terms of how things can be improved – this is one of the best tools you can have as a leader. It’s like having a personal magnetic force field pulling others to:

- See what others see, connecting with what others are thinking, doing, planning

- Align their projects around what the organization clarifies as its most important priorities

- Discover things they don’t know, for example, about the way the different functions of the organization work together as a whole

- Adjust the systems of how things are done (the very things that were invisible, intangible and frustrating)

It may seem hard to visualize work, but the biggest hurdle may just be believing you can share things visually. So many of us decide, “We can’t draw.” (Believe me, if making work visual actually required drawing talent, I’d be sitting on the sidelines).

Next time you find yourself wrestling with a problem, perhaps with an A3 or just a piece of paper in front of you, step over the barrier you’ve imposed for yourself, pick up any kind of writing tool, and just draw something, anything. An amazing thing will happen – your brain and your hand will start working together, ideas will flow, and all you’ll have to do is draw, scribble, organize, erase, and draw some more… and occasionally, laugh. Once we put our fear of looking stupid aside, new ways of looking at old things become not only possible, but probable.

In your day to day work, carry a notepad with you. When you hear people say things in a meeting, try to draw it. When you see things you want to think about more, capture it in a way that will remind you of what you saw. When you see connections between different pieces of work, draw a chain connecting those things together. Drop the fear factor by sharing your drawings with a team member you trust. You’ll probably hear a lot of, “Ah, I get it now” and “Can I see your pen for a second?”

I got this reaction myself when I went back to the quality improvement team after my coaching session with Mike. As I led the team back through the improvement story – imagining my audience to be completely unaware of our improvement efforts – I heard a few groans and some nervous laughter. We didn’t need Mike anymore; we could “see it” ourselves now. This making work visual thing was no piece of cake, but once my team and I realized the difference between doing the work and explaining the work – in other words, as Mike said, connecting the hands-on work to a clear business need people feel – the learning door was open again.

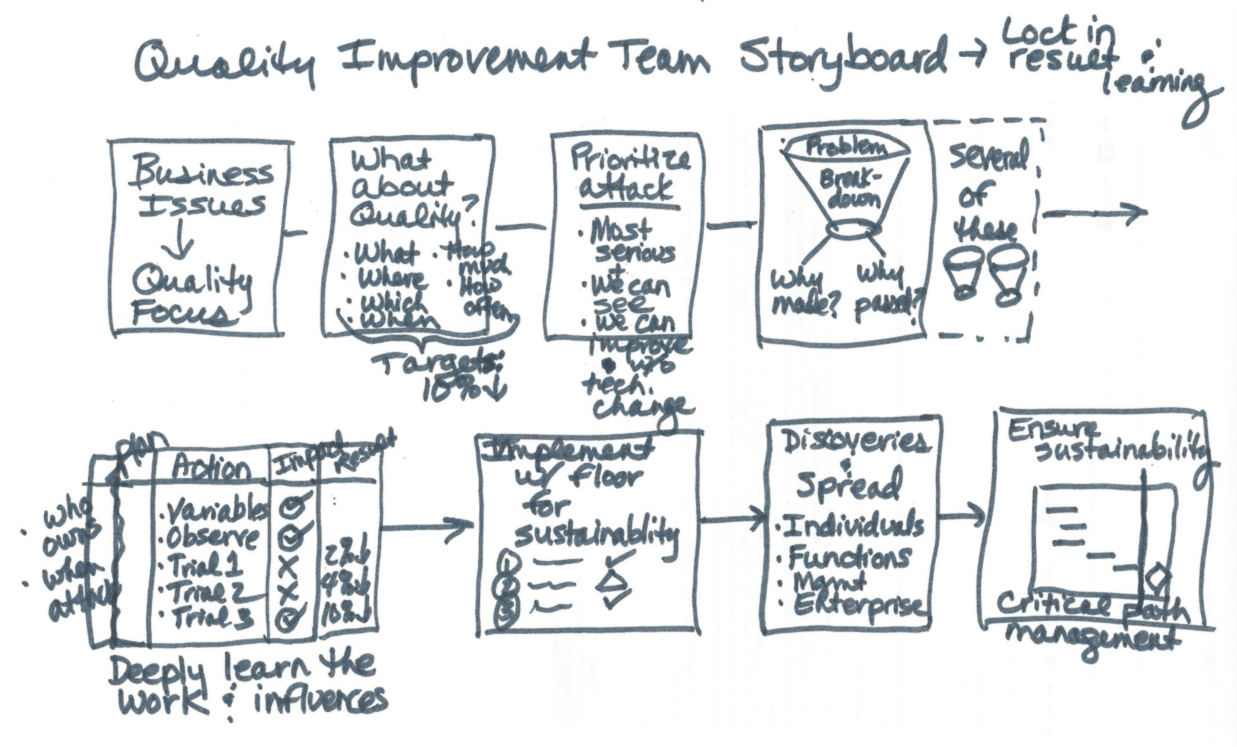

Mike had promised to come back when we were ready to share our story. A week later, after we had made a storyboard to explain the flow of what we had done and why, we invited him back. And sure enough, Mike said the words we had been waiting to hear. “I see what you did. And now let’s look at this together…”

Here’s a rough sketch of the storyboard we prepared for Mike.

As you can imagine, it was a pivotal learning experience for the group. More importantly, the Improvement Story answered questions for very important people. We got input and support from people all over the plant during the major activities. They had already helped without really being able to see what we were doing either. After reviewing the Improvement Story with them, now they were able to see how this improved the company’s ability to create real value for our customer.