Jobs and a Strategy to Create Good Ones

Every nation in the world is on a quest to create more jobs. As they should be.

But, we don’t want just “jobs.” We want good jobs. Our friend Zeynep Ton offers a prescription for good jobs. Ton, MIT professor and author of the Good Jobs Strategy, has seen jobs from many angles. Growing up in her native Turkey, Prof Ton had the opportunity to observe tough but decent paying factory jobs. In her university research in the US, where the economy has steadily moved from manufacturing to the service sector, Professor Ton has observed with dismay the sad state of service jobs and the wide variety of policies with which firms approach the employment of people under the pressure of harsh business strategies. But, the good news: Ton has also identified firms – like Costco, Trader Joes, Mercadona, and Toyota – that do a great job of treating employees right. And she shows how and why the firms reap the rewards just as well as do the employees. Read her powerful argument here and here.

Ton has spoken with us here at LEI a couple of times and argues that good jobs and lean thinking are neatly aligned. “For companies, good jobs are a prerequisite to operational excellence and TPS. You need to have it,” she said, adding, “At the same time operational excellence is the prerequisite to good jobs. These two are needed for each other—they form a virtuous cycle.” Her book provides detailed, concrete evidence that good jobs aren’t simply “good to have” but that the good jobs approach is a concrete strategy, in her words, one that combines investment in people, with specific operational decisions related to a company’s product focus, its balance of job standardization and employee empowerment, as well as tangible ways that employees contribute to continuous improvement. As she describes these characteristics of a good job, she asks with a smile, “Does any of this sound familiar to lean thinkers?”

The answer is, of course, yes it does. Lean Thinking, with its roots in the Toyota Production System, has a lot to say about all this, of course, beginning with addressing the question: what is a “job”?

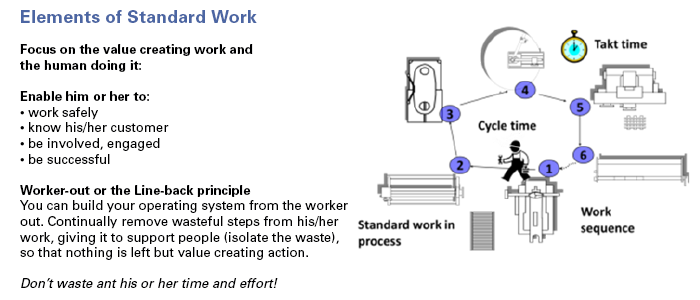

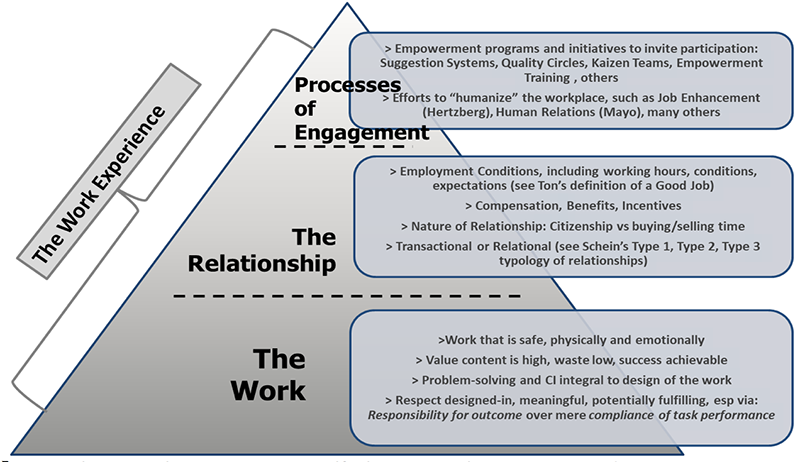

A job is three things. Three dimensions that together comprise something greater than their sum:

- The work that needs to be done

- A relationship

- Specific, documentable mechanisms of engaging people in their jobs, in the work they do

Together, these pieces comprise an ecosystem or overall work environment that results from the many decisions that go into making up three dimensions. A good job begins with good work. Let’s explore.

Fundamentals of the Work

Fundamentals of the Work

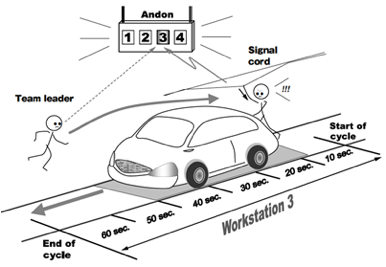

A job is made up of that most fundamental of lean concerns (right alongside the primary concern for value): the work. What is the work to be done to create the value? Lean thinking, borrowing from its roots in the Toyota Production System, has much to say about work, but, unfortunately, as lean thinking has continued its march from humble beginnings on the factory floor to frontiers of numerous kinds, focus on the work too often gets lost in the haze of change management theories, strategy initiatives, leadership development programs, and the like. It’s good to keep it simple: in any organization, we gather together every day for one purpose: to do the work. Tote that bail, pull that barge, process that invoice, acquire that company, sell that widget, scrub that heart valve.

The work pie. Work itself has three chunks and any attempt to understand it deeply must begin here: the value creating work, non-value creating work, and waste.

The Relationship

A job becomes a job (whether after the work has been defined or before) upon agreement between an employer and the employed. Say I need my trees trimmed and you are a teenager looking to make some spending money. I offer 40 dollars for what we agree is a couple hours work. We agree you will do the work this Sunday and I will pay you 10 bucks today and the remainder after I inspect the work that it has been done to my satisfaction.

Or, say I have a company and I post a position that pays $20 per hour for 40 hours per week, 20 days per month, 240 days per year. Weekends and holidays off, plus xx days paid vacation. If we’re in the USA and it’s any time since the 1930s, we probably have a signed, legal, upper case “contract” that binds us, that states the terms of our agreement.

Whether formal upper case Contract or informal lower case handshake-based mutual understanding, the contract between two parties – employer and employed – is the second piece of what constitutes a job. It is a relationship.

Not so long ago in the USA, a contract (formal or informal) between employer and employee was part of a broader social contract that served as an enabling mechanism for the greater society to function effectively. The steady erosion of employment relationships as social contract has led to huge segments of society struggling without a safety net to ensure provision of basic human needs. In recent decades the argument has gained currency that workers could always retrain themselves as companies were free to chase willy-nilly whatever latest trend promised the highest profits. After all, if technology and customer needs combine to mean we don’t need many millwrights, we can’t simply keep people busy running mills just for the sake of running mills. But, it is simply naïve to think a 50 year old millwright is going re-educate himself to become a software engineer.

Thus, social contracts and business realities sometimes collide. Often one side loses. If there’s going to be a loser, it’s usually the worker. It’s worth noting the incredible lengths Toyota has gone to, time and again, to ease the pain or to avoid job loss altogether.

In earlier days, it was common to make statements such as “a day’s pay for a day’s work.” Those platitudes sound old-fashioned in contemporary language but actually form the basis for employer-employee work relationships even today. Indeed, what is a day’s work?

Is a day’s work a matter of time, a matter of using up eight hours? Eight hours doing what? Being on the premises? Most people would say no, it means eight hours to do some task or set of tasks. So, are we agreeing on the time spent (8 hours) or tasks worked on, work completed?

There’s where it gets interesting. Out of eight hours, how much time is spent “working”? If “work” is a matter of time spent, then the entire 8 hours is “work.” But, if “work” entails effort expended toward accomplishing tasks, well, that is another matter entirely. This, then, is where the two basic chunks that make up a job – the work and the contract – intersect. (We shall see them intersect again in the formation of an ecosystem.)

Time ≠ work. Motion ≠ work.

The much maligned time clock, cursed by laborers as a virtual ball & chain pinning them like slaves to their work stations ensured only the potential for work to be done, it never ensured it actually would be done and certainly not done in the right way. So, supervisors and managers (themselves merely employees of a different class) clung onto the thing that was easiest to see – they looked for movement. Keep everyone and everything – every human and every machine – moving. Keeps things humming. Like a big machine. Charlie Chaplin and all that.

It’s time to replace the time clock with the work pie.

This is work that is “standardized” but fully engages the whole human, feet and hands, head and heart. This is what Prof. Ton is seeing at some (too few!) companies, and what we have seen at companies in the lean community over the past 20-30 years. But, the number of companies that go this far remain too few and far between. One factor: integration of various subsystems in which integration can best be understand at (you guessed it) at the level where the work is actually done.

The Ecosystem and the Work Experience

Observe your work, how it is designed, performed, improved – that is where you will find your culture.

Organizational cultures are complex systems. And systems, or ecosystems, we know are difficult to design. Choose your favorite organizational systems theorist: Edgar Schein, Russel Ackoff, W. Edwards Deming, Peter Senge – they all say essentially the same thing about the nature of systems dynamics. Systems are complex and system design is an aspiration as much as it is a science.

Deming wrote: “A system must have an aim. Without an aim, there is no system. The aim is a value judgement. Joining an organization is joining an aim, whether well- or ill-defined.” How about we make it our aim to create great value for customers through providing great jobs for people? Back to the deep linkages between lean thinking and Zeynep Ton’s Good Jobs Strategy.

This is far more than an add-on empowerment program. It is a different view of work itself. We’d like to blur the distinction between work and worker, maker and object. We want to integrate people development inextricably with the design and doing and improving of the work. This gets to the heart of lean thinking and practice: products are a function of the people who make them; to make good products, it pays for organizations to invest in developing people. This is true for factory work, office work, service work, managerial work, knowledge work. If it can happen on the factory floor, it can happen anywhere.

“100 Years of Innovation in the Work”

“100 Years of Innovation in the Work”

Most process improvement initiatives, including so many “lean programs” never go this far. They stop at addressing only the technical side of the equation, ignoring the human side. In those instances, companies are practicing scientific management with perhaps some good industrial engineering. But, the technical side of lean practice without the social side isn’t lean at all.

Other “lean programs” and organizational development initiatives address only the social side, “human centered” programs often with sophisticated engagement and empowerment programs, many harkening back to Frederick Hertzberg and Elton Mayo. But, as above in reverse: the social side of lean without the technical side isn’t lean at all.

My observations tell me that the lack of balance among firms in 2017 is split about evenly between leaving out the social side versus leaving out the technical side. What do you see?

There are more aspects to creating a great job than improving the technical pieces of the work itself. Equally true: there are more aspects to creating a great job than tending to only the social side, too.

- Actually design the work. Don’t let it just evolve. Don’t devolve into laissez faire in the naïve belief that since “the people who do the work know it best …” you can therefore simply leave it to “them.” Understand the needed outcomes, the tasks, the specifications (quality, performance, other), the steps, the sequence, the timing. Be engaged.

- Tend to the social side. Understand the individual levels of engagement in the work, but also the relationships, the levels of trust, the interactions. Think of it as a social design project.

- Actively create the environment itself. The setting, the ecosystem and its components. Be engaged in the unending PDCA required to move from A to B to Z. Think of even this as a design project. A very complex one that needs YOUR engagement.

And recognize that these considerations aren’t ancillary to your business strategy – they are integral to how you create the future you want, integral to the becoming of your future. If we all do this, we can make companies and economies that provide more prosperity for more of us.

Here’s a way to see how it all fits together. I invite you to print it out and play around with it. A version for your company might have different points of emphasis here and there, and it should certainly have more specificity. I hope it’s obvious how actualizing all this has to be a multi-functional endeavor. HR: this is your chance to step up! (But, don’t try to do it alone!)

Note how this ties together several dimensions of the Lean Transformation Framework (link to animation): your basic thinking foundation, your work design and people development pillars, and your desired leader behaviors (actually behaviors of everyone, not just “leaders) and management system. (And never forget to tie it all back to your purpose, your problem to be solved, the job to be done!)

Want Better Employees? Be a Better Employer.

So, the lean thinking philosophy of job design holds that the technical/process and the socio/people sides of the equation to create a great work experiences are equally important. Well-designed work recognizes all the social and technical factors that go into producing the right quality at the right cost in the most timely way possible, with performance consistently improving over time. Treat employees well and with respect, and you can expect them to do their best. Leave out the social or the technical side and pay the price. Combine great work design with exemplary treatment of the humans who do it, and, as Zeynep Ton argues, reap the rewards.

We want more jobs, but we want them to be great jobs. And a great job needs great work.

John Shook

Chairman

Lean Enterprise Institute, Lean Global Network

PS: For the title of this letter, I owe apologies to the great country music artist Ernest Tubb, who ended his performances with: “If you want better neighbors, be a better neighbor.” A good sentiment for many of the world’s problems, if you ask me. And that’s why we chose “Want Better Employees? Be A Better Employer” as our theme for the 2018 Lean Transformation Summit in Nashville, Tennessee, (just a block or two from Tubb’s famous record shop on Broadway) March 26-27. Join me and presenters from TechnipFMC (creating great jobs for product designers!), MAS Holdings (creating great jobs no matter where in the world you operate!), American Family (creating great jobs for 90 years!), and many other presenters who will share their efforts to build better companies and jobs through lean thinking and practice.