Dear Gemba Coach,

We’ve drawn the value-stream map of one of our complex production processes (17 steps), identified the key bottlenecks, and improved the process. Yet, six months later, the performance is just as bad as it was before – what are we missing?

Nothing … Everything? I have to start by pleading guilty. Back in 1995, I wrote a book about process reengineering. I was fully committed to the idea that “it’s always the process, never the people,” and “put good people in a bad process then they’ll perform badly” and so on: change the process, change the performance.

I still subscribe to this but in a completely different way.

This time last week, I was sitting in a crowded restaurant, chatting with the COO of an industrial company. We were deep in conversation in a noisy place and the waiter was trying to read us the specials – when in fact we had already made the banal choice of two chicken Caesar salads. The waiter started complaining we were not listening to him – we weren’t. The peeved tone made us look up, probably not very nicely, and the waiter responded with a put-down, and I suggested we go for lunch somewhere else and … eventually, his boss intervened and handled our lunch from then on which went back to bland food and interesting conversation.

There was nothing particularly wrong with the process: seat people, hand over the menu, give them the specials, take the order, serve.

Most processes are designed to work.

But then real life intervenes in 1) difficult conditions (at that time of the day the restaurant was very crowded and busy and staff overburdened) and 2) ambiguous situations (we had quickly made our choice, the waiter is instructed to sell the specials, we were all rushed).

In unclear conditions, when people get hit by an unexpected small variable, they tend to misinterpret, react wrongly, and suddenly an incident appears out of nowhere.

From the study of “normal” accidents we know that when humans are faced with one curveball, they usually cope. When a second thing goes wrong at the same time, it gets hard, and at the third (in our case, the table next door was trying to get the waiter’s attention for water they had requested but hadn’t received), people lose it – particularly when the environment is loud, noisy, stressful, confusing. When they lose it, they react exactly the wrong way and things can get very messy indeed.

No Correct Way – Ever

In our traditional thinking, we are obsessed with looking for the “right” way to work. We’re seldom interested in acknowledging there will never be a clear “correct” way to work, but an infinity of wrong ways which can be discovered and mapped and avoided – real knowledge.

Before changing the process in any way, a difficult (and more reasonable) challenge is to figure out how it behaves in different conditions. It makes sense to map the process, but first to look for case-by-case problems.

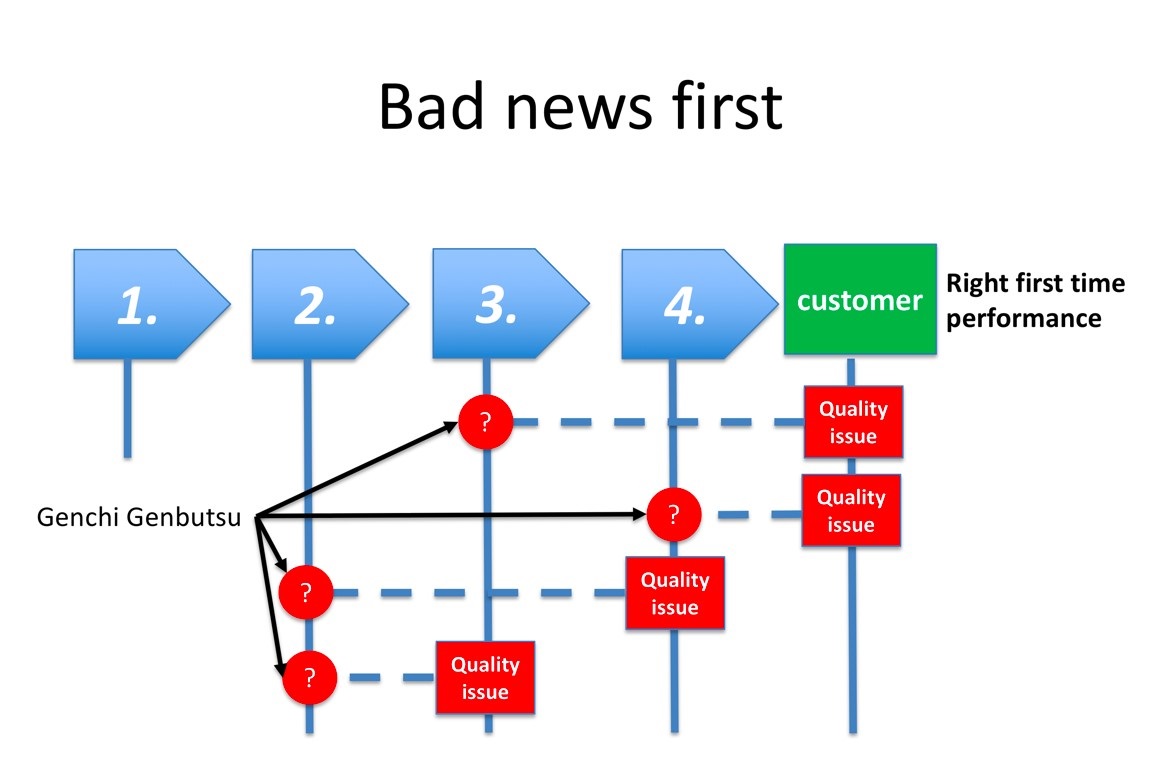

Map the process on a wall, and then start collecting the bad news by adding quality issues and where you believe they originated.

Then, rather than look for process issues, go and see at the gemba to figure out what causes and conditions real people are really faced with:

- How clear are the working environment and job purpose?

- What sort of jarring events are they likely to be dealing with (this varies greatly from one place to the next)?

- How well do they understand how the process handles these cases and the impact on overall performance?

- How trained are they to react correctly to make the process perform and not make matters worse?

The next step is to train and train and train people both to the basics of the job to get it done, according to the current process and then to problem awareness and solving so they better recognize situations that are going south.

Then listen to them and change the process one change at a time.

3 Challenges and 2 Facts of Life

A great lesson of lean is to make what you have work before you start changing it, solve problems to understand more deeply what is happening and then kaizen one change at a time when you know where you’re going (For instance, in the restaurant’s case, the indifferent food is at least as much of an issue than an overworked waiter).

More deeply we have three great challenges:

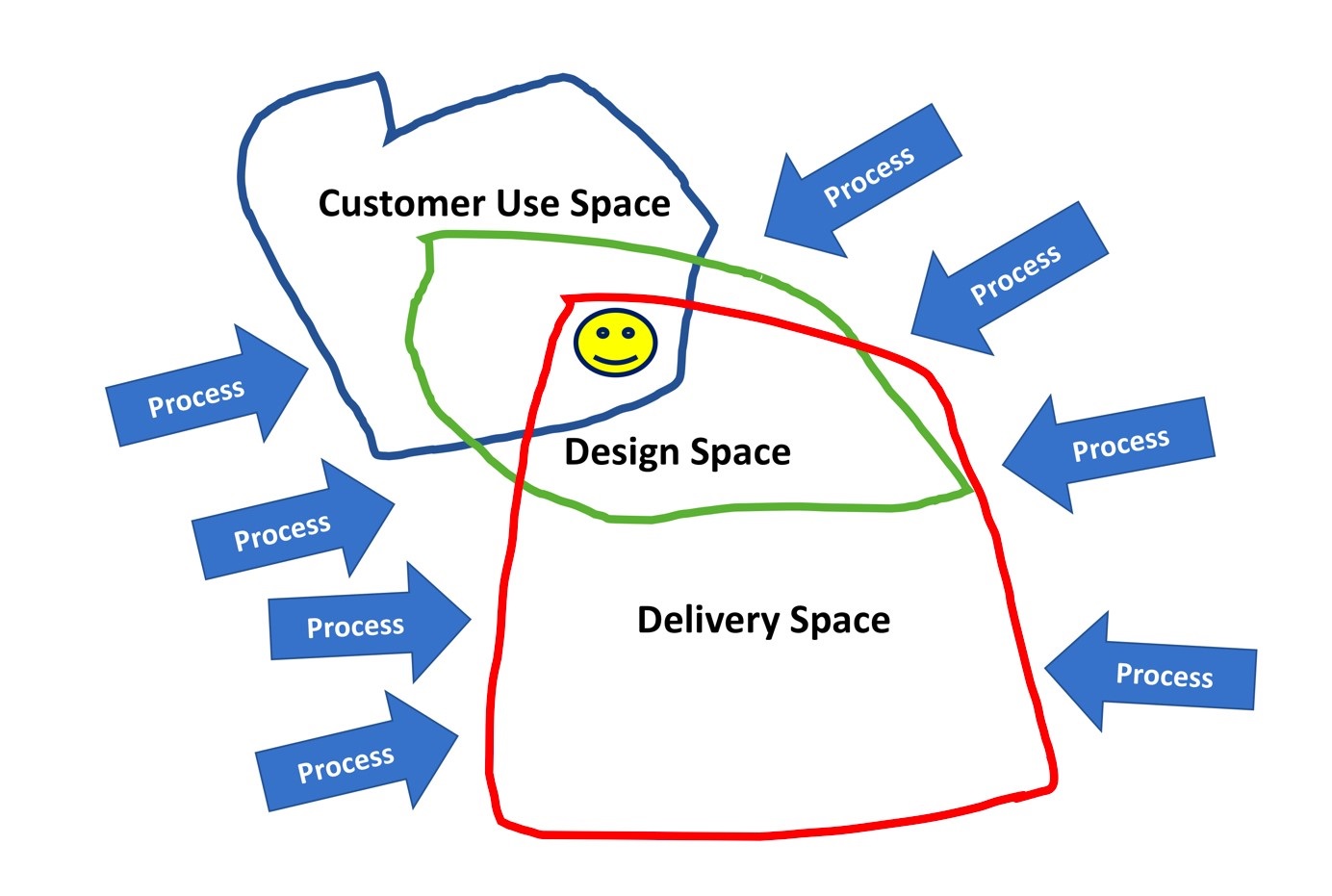

- Understand the customer use space

- Understand the design space

- Understand the delivery space

Products are the result of the interface between customer use space and design space, technical processes are the result of the interface between design space and delivery space, and company organizational processes are all around – supporting, or, on the contrary, hindering.

We have to accept two facts of life. First, these spaces will always be mysterious to some extent, which means that if we’re serious we need to keep looking for knowledge gaps all the time (and specialized functions, such as marketing, engineering or production tend to reduce the mystery to their own worldview). Second, processes are designed to handle the most common case, tend to be “sticky” (as in, difficult to evolve even though the need changes), and interlinked, and, thus, tricky to change.

Ironically enough, the discussion with the COO was exactly about that. Since the start of the year, his CEO had used a windfall of cash from a good operating year last year to push hard for a “digital transformation” by launching several “breakthrough” projects at the same time, and, as a result, confusing everyone in the organization and losing business very quickly. They were trying to salvage the situation by reducing the number of simultaneous changes required of employees and crafting better explanations of why and how.

In this sense, all “genchi genbutsu” activities are indeed about problem solving (teaching people to better cope with a variety of conditions and look for causes) and on-site learning (learning to fill the knowledge gaps in the customer use space, design space, and delivery space).

A rather long-winded answer to a question that is deeper that might seem at first go. Yes, the temptation to just “fix the process” is huge, but as you’ve found, it doesn’t amount to much unless the fix stems from: 1) understanding deeply the value the process brings to customers, 2) knowing how it was originally designed and with what ideal in mind, 3) training people to cope smartly with special cases and, 4) listening to their suggestions for change and supporting them in carrying out the changes, one step at a time.

The process to fix is not the “process” itself, but the process to develop people so they have a better understanding of their job purpose, a greater awareness of conditions, a smarter handle on causes and countermeasures. Then they can contribute to both fixing processes one change at a time for higher performance and making sure the fix sticks.