Honestly, I have no idea; every company is different. The director of one train maintenance center I know has just installed an andon – the experiment is in its early days – and it has proved to be an interesting experience.

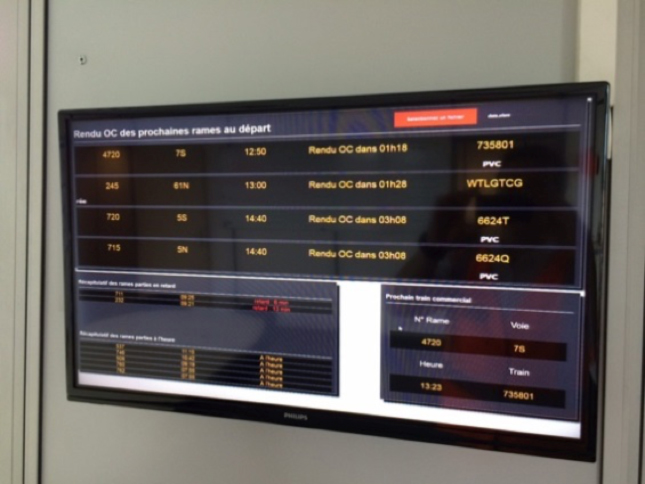

Train maintenance work occurs over very large distances as teams work on various sections of the train. To get started, they installed a very simple system that highlights when the train is not ready to depart on schedule, for whatever reason. The system is automatic, and doesn’t involve operators pulling the line, and so in line with the earliest andon experiments at Toyota (many andon calls are still triggered by the machine itself detecting an abnormal condition).

The center director has a screen in his office reflecting the andon screen set up on the team leader area. He sees what they see.

The first discovery, obvious in hindsight, is that most of the work is done very early in the morning to get the morning trains off, well before any manager arrives on site. The first question the director and his team asked themselves is whether they should make an effort, at least on some days, to show up early or let the guys get on with it (as they’ve done forever).

The second reaction was also interesting as the andon flashed a lot of “false alarms.” Management felt they were false alarms because the andon was mechanically reacting to checklists not fully ticked off, or other detail problems that did not impact the actual departure of the train on time. With a bit of thinking, the director realized these were not “false” alarms. They were alarms, period. The andon was showing them something they had not looked at before, and in doing so revealed the prevailing mindset.

This is classic because let’s keep in mind that the entire purpose of the lean toolbox is to surface misconceptions and to transform management’s mindset. The core assumption revealed here was that the andon should reveal burning fires — issues that would stop the train from leaving on time. In fact, the andon was flagging much finer “out of normal condition” issues.

In quality terms, this is a fundamental issue. Shigeo Shingo used to talk about “death certificates.” Most quality systems are there to track bodies once the accident has occurred and fill in the paperwork after the fact. The real issue is preventing quality mistakes, not managing them once they’ve occurred. This is why the old-time sensei were so pushy on materializing the difference between “normal” and “abnormal” conditions.

Change These Assumptions

Which is exactly what the andon was doing. Managers are discovering that they have to learn to go and see situations that are fine but where something has tripped the andon. No more firefighting, but a deeper look at normal situations to see the potential problem, the “bud” of the problem. This involves changing two rather deep managerial assumptions:

- Catch people doing good work: Go to the gemba to look at detailed work but no burning fire, and learn to work with people on improving normal situations as opposed to always correcting problems. In this center, management has already learned to do that with repeated 5S workshops and work on team ownership and improvement of work areas, but here this is pushing the idea to the work itself. Andon works just as well to see that things are going fine, but some detail (that tripped the andon) can be improved.

- Being interrupted from doing their work to check the local conditions of value-add work: The andon trips randomly and typically interrupts management, from front-line management to the center’s director in the course of their administrative work. Imagine trying to read a book at the park while watching a child. Of course you’ll look up regularly and rush in at the least sight of danger or trouble. Forget the book. The idea is to get the child down from the tree before he falls. Managers must therefore learn to see their administrative work for what it is: necessary muda, and refocus their attention on the gemba.

Ultimately, the andon is teaching the maintenance center’s management team to reassess their relationship with the gemba. Their job is not just to be the main firefighters to jump in and save the situation once the fire is burning – of course they have to do that, they’re maintenance guys. But also must be caretakers of the conditions so that fires won’t break out. This means spending time on the gemba when things are running normally, learn to talk to teams about their standard work and not just catch them out when they do something wrong, and progressively understand friction – how innocuous grains of sand can cause large problems.

Inspect Conditions

I have no idea what your own andon will teach you, but the main topic of jidoka is to shift from post-hoc quality issue management to making sure the problem will not occur. Our core challenge is to shift from post inspection – catching the defect at the next process when something has gone wrong – to self-inspection – catching the defect while it is being made in current production – to source inspection, inspecting the conditions so that the defect is impossible. As you can imagine, in maintenance, this is far from easy because of the spread of work.

…see sndon as a way to involve your employees in helping you figure out the true nature of the work.

What I do believe is that you have to see andon as a way to involve your employees in helping you figure out the true nature of the work and not a tool to jump in on people and “tell them” how to do their job right. The basic, basic premise about andon is that we’re passionate about our product and service and andon will help us to see previously unrecognized aspects of our work, in smaller and smaller details. Andon changes our relationship with the gemba and, as the old-time senseis used to say “gemba is a great teacher.”

Building a Lean Operating and Management System

Gain the in-depth understanding of lean principles, thinking, and practices.