During the past four years working at Lean Enterprise Institute, I’ve interviewed more than 800 members of our community seeking help or support in their individual learning and organizational transformations. One question I often ask is how each person first became aware of lean thinking, and how that exposure led them into practice. Spending my prior 13 years in manufacturing, I was very fortunate to learn about lean in 4 distinct approaches, each of which built my practice and deepened my understanding in its own way:

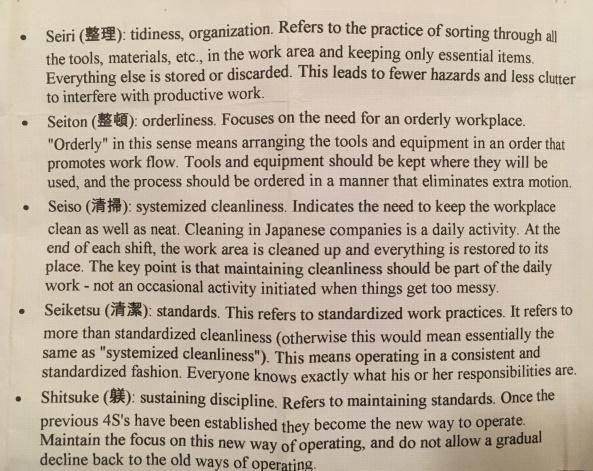

My very first exposure to lean was through a “5-S event.” The organization sent a team member (Jeff) out to a training class, de facto appointing him to lead the company’s lean endeavor. Upon his return from class, a day was set aside, and a front office “5-S” extravaganza ensued. This was my very first exposure to the world of lean. I still have an artifact from that event, a piece of paper Jeff handed to me explaining “5-S.” What I read resonated at an intuitive level, and I was curious to learn more:

Needless to say, organizing desks and cleaning up the work area, however fervently and well-intentioned, does not a 5-S system make. The sincere effort, unsupported by any other context, could not sustain (it never had a chance). The overall lean endeavor, so hoped for, lost its luster and faded away to higher priorities, firefights and heroics.

We tried once more like that, with a different team member, Mike G. (implication: It must have been Jeff’s fault?) Mike set up shop in a double-wide cube filled with resources, whiteboards and inspirational quotes. Ill-equipped to navigate the social-technical terrain, Mike never quite made it out of his cube. Any further understanding from this brief era would be theoretical.

“You have to understand that the very idea of experimenting on LIVE work, with PAYING customers invoked sheer terror from the leadership team.”

Our third lean era was the age of Albert. A bright, energetic, knowledgeable consultant with years of practical experience, deep TPS knowledge and the warmest, kindest heart you’ve ever known. The trouble was wrestling an area for improvement that management would sign-off on. You have to understand that the very idea of experimenting on LIVE work, with PAYING customers invoked sheer terror from the leadership team. “What if the experiment failed? How could we deliver? What would we say? No- it’s too important, too risky, we don’t have time to experiment, to learn, to improve.” And failure was not an option- this was the mindset, even at the expense of learning.

Here we had a living breathing practitioner, and a few people willing to give this a road test, but nowhere “safe” to learn. At the time, I was managing a $5 million piece of business that was operating in the shadows of our #1 customer. It was the stepchild account that no one paid much attention to. Accordingly, it was rife with waste, long lead times, frequently renegotiated schedules, quality issues, etc., a perfect playground. I knew the work inside & out, knew all the ways it went awry on a daily basis, how much it (and our relationship with this customer) would benefit from the attention and any improvement. Not yet understanding anything more than what 5-S was, I approached Albert and asked if this work would be suitable.

Jackpot! I will call this the first way I learned about lean, through Shop floor hands-on Kaizen. We invited the customer fully into our process, studied the work and mapped the value from beginning to end, recognizing the waste. We identified product families, calculated takt, observed cycle times. We measured throughput, capacity, and the materials, equipment and operators needed. We aligned on the right batch size, formed a team, and repositioned the equipment on the shop floor into a manufacturing cell. We walked the floor daily at 9a, we huddled twice a day morning and evening, we met as a whole team, including operators, once a month to talk about quality and performance. The work accelerated, became visible. We began delivering on time, with less scrap. The most impactful thing I remember is the wholehearted effort and the way the weekly client calls went from hour-long excuse-fests to respectful 10 minute check-ins. We built accountability into our process, and trust into our customer relationship. It was an excellent way to learn.

“The most impactful thing I remember is the wholehearted effort and the way the weekly client calls went from hour-long excuse-fests to respectful 10 minute check-ins. We built accountability into our process, and trust into our customer relationship. It was an excellent way to learn.”This way of learning accelerated my learning curve, because I was learning through doing. Learning through trial and error, through my hands, eyes, ears, and in the midst of experience. Rather than theoretically understanding “product families,” from the shop floor perspective we could look at the routings, look at the materials, SEE how different products had different needs, followed different paths, making the logic evident. We didn’t learn how to take a gemba walk; we TOOK gemba walks, and learned how to to do them better each day. We didn’t theorize around when where and why to huddle; we huddled, because we needed to. We made mistakes, we learned from them. It wasn’t until afterwards that I learned the names of the tools, features, methods we applied.

Riding on the success of the manufacturing cell, our company decided to invest further. We developed a Lean program (PEP, we called it) and our courageous leader Mike W. wrote for state funding to secure classroom training for the entire company. We were awarded the grant, and hired an organization to come on-site and teach a lean curriculum, weekly, to all employees: Classroom training. Previously, during the effort on the shop floor, I learned about methods (which we didn’t always stop to name and explain). Here in the classroom, I learned about the tools. Basic simulations illuminated the common-sense simplicity of single piece flow in pull systems. In the classroom, I gained a perspective and foundation for the tools we used, and what it was we’d actually done previously out there on the shop floor. Aside from the general exposure and awareness, we developed a vocabulary around lean; a way to talk about a better state. But the biggest influence classroom training had on me was the gift of a voice.

By this I mean the ability to express a healthy discontent with status quo. Learning in the classroom environment with 25 of my peers served as an encouragement – and even an expectation- from the organization to offer productive alternative ways to “the way we’ve always done it.” Anyone struggling in the vortex that is both mountains of WIP, yet an inability to deliver on time can attest to the fact that there MUST BE A BETTER WAY. The classroom training exposed that better way to the entire group of individuals fostering the status quo. It was no longer some crazy scheme to consider doing things differently. Here, in fact was a way. There was no more excuse for our collective mediocrity, and we were empowered to say so.

As our classroom training program came to an end, we hired a full time Lean Coach (Paul) on staff. This coach worked with individuals, cross-functional teams, and departments, to develop individual’s capabilities for lean thinking and problem solving. Until working with our coach, I’d not thought of Lean as a way to think. Up until then it was merely a set of tools applied through these methods that had a remarkable effect on the work. It simply didn’t occur to me that Lean might be an epistemology. A way of thinking, maybe even a way of being. I remember things came into view as clearly as a dawning sunrise when I realized that value, waste, pull, flow, pdca and problem solving were ways of behaving as much as tools to apply to the work. That learning came through working on a team to design and pilot a new system (in effect a “service cell”) in our administrative area of the business. Shortly after testing, proving and implementing the service cell, I began to learn A3 problem solving through one to one coaching.

That was May, and by August of that year I was at LEI, having journeyed over 5 years through 1-off events, shop-floor improvements, classroom training, and individual coaching into my still very basic understanding of Lean thinking and practice. As you can imagine, the learning has continued. A new dimension to my learning has incorporated books (like Kaizen Express and The Work of Management) to walk me, at my pace, through the more complex things I experiment with. My forays into mapping my own work, developing Kanban and supermarket systems, as well as iterating visual management systems has been rooted in experimentation reinforced by books, and supported with coaching.

Each approach to learning Lean brings value into my work and improves my capabilities. There isn’t one way (for me) to get there. In my case each situation called for a different approach, and each approach to learning showed me a different dimension, making Lean Thinking more accessible, deepening my understanding and developing my practice.

How did you first become aware of lean thinking, and how has that exposure led you into your practice?