Dear Gemba Coach,

I’ve heard of hoshin kanri and I’d really like to try it in my company – anything in particular to keep in mind?

Hoshin kanri, like many lean tools, is both powerful and a little dangerous. The danger is, as always, to implement the rituals of the tools without quite grasping its purpose – in Hajime Ohba’s terms, to build the Buddha image without placing the spirit into it. Before you introduce this tool in your company or department ask yourself:

- Am I looking for a communication tool to make sure we all understand the direction of the company and how each person can contribute?

- Am I looking for a planning tool to make sure objectives cascade consistently and that local action plans are aligned with higher-level objectives?

If you’re after the latter, beware. Planning is essentially about turning unpredictable into predictable – creating action plans about the future. Planning works well in steady situations, less well for exploratory challenges where, by nature, tomorrow is not known and good ideas will emerge from flexible responses to uncertain situations.

Hoshin kanri is not a planning tool. Its main purpose is to communicate the general direction top management seeks in a way that leaves both latitude to operational units to formulate their own plans, and to reveal difficulties so they can be helped. To my mind, the key points to keep in mind are challenge, catchball, teamwork, and support.

Challenges vs Goals

Challenges are an expression of the large-scale problems the CEO thinks the company should face. They’re usually quite broad, for instance:

- Earn customers’ smiles.

- Double inventory turns.

Challenges should be stark, clear, simple, not necessarily quantified. They are beyond goals and objectives. Challenges express a direction for improvement more than a target to reach. Challenges frame “we must be radically better at this.”

In complex, turbulent environments, people’s mental space tends to be cluttered with the endless stream of tasks to be done, problems to be faced, situations to be turned around, relationships to be fixed and so on. The accelerating pace of information means that it’s becoming harder and harder to see clearly how to prioritize or where to focus. Challenges represent the peak on the horizon where everyone can understand that the CEO wants to go “that way,” even though the path itself is not set.

Catchball is the essential technique to setting the path. Each department head is tasked with setting:

- Their objectives to respond to the challenge.

- How they plan to go about reaching those objectives.

For instance, in one large CEO association, the head of the conference department chose to respond to the challenge of earning customer smiles by setting the objective of reducing customer complaints at conferences by half through (1) taking better care of luggage (When CEOs arrive in the morning at the conference, they don’t have time to check in their luggage at the hotel, so the conference organizer took it on.) and (2) better catering.

The supply chain manager of an industrial firm responded to her CEO’s challenge to double the inventory turns by setting an objective of cutting purchased parts inventory by half over two years through the implementation of supplier milk runs.

Once the department heads propose an objective and a general plan, the CEO can then discuss with each of them to challenge their objective (too ambitious or not enough) and their plan (are you sure that’s the right way to go about it?). But overall the manager remains in control of his department’s plan and ambition as long as the link to the overall challenge is clear: if we achieve these objectives through this plan, we will have visibly moved forward toward the given challenge. The outcome of these talks is an agreement from senior management of the proposed plan – objectives and proposed action.

Turf Wars

An important part of hoshin kanri is cross-functional communication. Once each department has set its plan to move forward, the challenges can be expressed in terms of common goals by choosing how to quantify them in a way that sort of makes sense for everybody: easy for inventory turns, harder for earning customers’ smiles.

The next step is then to organize a roster of presentations where department heads present to each other problem solving A3s explaining how they will overcome obstacles to achieving their targets. Cross-presenting is a critical part of the hoshin kanri process as functional departments share what they’re trying to achieve, what they have in mind and the trouble they run into. This is an essential platform for other departments to understand what their colleagues are going through and how they can help – or at least stop hindering without realizing it.

For example, the engineering department might realize that frequent engineering changes coming randomly might make it difficult to establish the good relationships needed with suppliers to make milk run routes work on a daily basis. Engineering might then consider that part design changes should be released to suppliers on a regular rhythm rather than unexpected batches, to give suppliers the space to work on these changes one at a time, and give them the opportunity to succeed at the milk run program, thus helping the supply chain manager achieve her objectives, and thus helping the CEO succeed at her challenge of doubling turns.

Without such regular communication, functional departments are likely to try to achieve their objectives without regard for the impact of their actions on the full value stream and at the expense of their colleagues, triggering the usual turf wars and corporate rivalries.

Finally, hoshin kanri only makes sense if objectives are met. If goals are not met by far, then the whole exercise is pointless and loses credibility in people’s eyes, becoming one more mindless corporate rain dance in which staff know they’ve got to participate for show but don’t bother to turn their brains on to figure it out.

The visualization of hoshin kanri should reveal clearly where goals are not met and why (according to the function experiencing the difficulty). Senior managers commit to gemba visits to see the problems for themselves and commit to finding ways to help out so that targets are met. Does the function head need more capacity? More expertise? A different way to think about the problem?

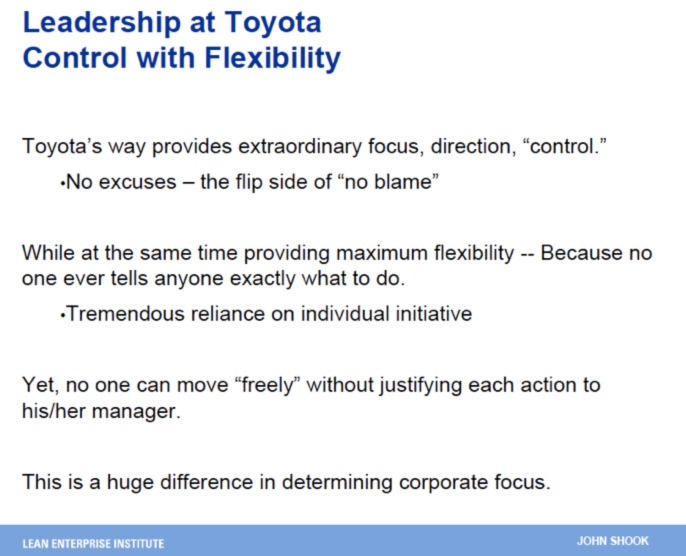

As John Shook explains, this creates a very different managerial environment from what we’re used to:

Hoshin kanri is not about planning but about sharing (1) clear direction and a (2) strong commitment to achievement. Before you start you must think seriously about how hard you are ready to support your department heads in achieving their intended results. The aim is to build on success (even small ones requiring a lot of effort) to demonstrate that we can achieve great things together, not creating one more platform to conclude that nothing ever gets done because senior management announces goals without any real intentions to do what it takes to reach them.

Tempering Big Company Disease

Lean is not a better organizational design method. It was born from Toyota’s realization that growth inescapably brings Big Company Disease:

- The company focuses more on internal processes than on customers’ preferences.

- Department directors solve their own internal problems at the expense of their functional colleagues.

- Senior leaders select pandering middle managers who do their best to keep high potential (and difficult) people from having opportunities to shine.

- Heritage technologies are taken for granted and legacy stops the acquisition of new technologies.

Practicing lean means that one realizes there is no escaping Big Company Disease, but tempering it somewhat is enough to develop real competitive advantage. Lean techniques focus on giving everyone the opportunity to find a “plus alpha” factor in the way they do their work to satisfy customers better, in their terms not ours, to better work across functional barriers, to give bright people space to grow and to nurture our proprietary tech as well as develop new, unfamiliar ones.

Hoshin kanri is a very powerful tool to do so. However, as your question suggests, one must be very aware of its pitfalls. If used as a transactional planning technique it can turn on the management team by creating further frustration, demotivation, and disengagement. To work as it should, hoshin kanri requires from management both a very clear vision of the improvement dimension, and a strong practice of gemba walks to see the reality of work situations first-hand and understand people’s strengths and weaknesses well enough to have practical ideas on how to help them reach their own goals even when they’re stuck.

Management must also have the courage to face the fact that things don’t always go as planned, and the presence of mind to recognize creative ideas born from difficult situations. The promise is real, but making it happen requires already a firm grasp of lean principles and practices.