Last month I had the good fortune to join a gemba walk with the former plant manager of Toyota Motor Kyushu’s Miyata Lexus factory, Hideshi Yokoi (you can read more about him here). We spent about two hours walking the floor of a major automotive supplier with several members of the executive team.

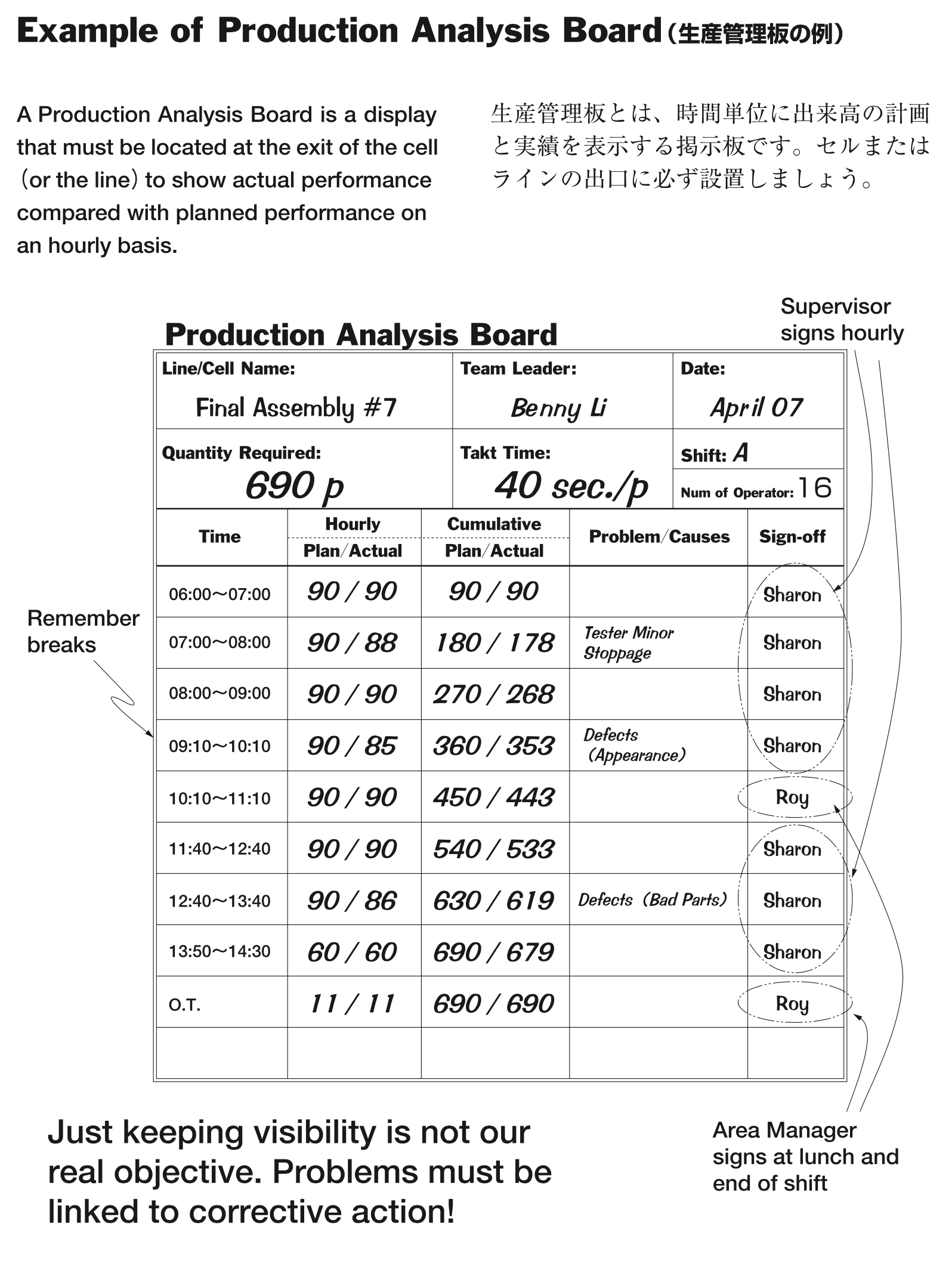

While observing a cell, Mr. Yokoi asked, “What is the production plan? And how are you doing against the plan?” Inside Toyota (and many other organizations) this is tracked on a simple paper chart called a Production Analysis Chart. Hour by hour a team leader writes the actual production against the planned production along with problems that kept the team from achieving the target.

In order to answer Mr. Yokoi’s questions, the team leader had to log into a computer using a passcode, click through some windows, and read a complicated chart. In other words, a computer knew the answer while a person did not.

Mr. Yokoi became visibly upset and began asking the leadership challenging questions about the role of management. Most notably, he asked them, “What exactly does a manager do here?”

I have since spent much time wondering why Mr. Yokoi read so much into the company’s management structure and capability through this simple observation. I’ve come to believe that the Production Analysis Chart represents much more than simply planned production versus actual production and the problems that are causing gaps between the two. Instead, the chart (an example from the book Kaizen Express is shared below) is a figurative and literal social contract that binds management and workers together.

The terms of this contract are:

- Management and the team knows what is meant to happen in this job

- Management knows what is actually happening in this job

- Management promises to address each barrier that prevents the team from successfully doing the job; in other words, management promises to remove excuses

The simplicity of the Production Analysis Chart belies the complexity of the social fabric it weaves. Let’s go through each of the terms one by one.

Management knows what is meant to happen in this job

If production is not stable, then what meaning does a plan have? How can a manager know what is meant to happen in a state of chaos. Chaos is unpredictable. A manager must first make sure a job is consistently stable. At a minimum, this demands that machines work and parts and tools are available. Ostensibly simple, maintenance of production stability, never mind production kaizen, is a demanding responsibility.

I recently spent a week at a different automotive supplier – which I’ll refer to as Company X – alongside members of the Lean Global Network. Several of us worked inside of a cell that commonly experienced an hour or more of machine downtime per shift. Moreover, operators were responsible for supplying their own parts, resulting in frequent departures from work stations. Though a simple analysis revealed the cell could function with two fewer team members, this cell could rarely meet its production plan. The work was not stable.

On top of basic stability, consistent achievement of a plan requires repeatable work. Management must design jobs that operators can consistently complete within a defined cycle time and with perfect quality. Naturally, they must also sufficiently train operators so they have the requisite skills to successfully execute the job. If work is not repeatable, then how can anyone know when a deviation from the plan has occurred?

If a manager is to assign workers a production target, a manager must also assign himself responsibility to create a stable environment that allows achievement of that target. Otherwise, operators will be left to fail. The relationship between management and workers will collapse.

Management knows what is actually happening within this job

Reality rarely goes to plan. Problems inevitably occur. Assuming Term #1 of the contract has been met, management and operators will have an environment that at least allows for awareness of deviation from plan. But just because awareness is possible does not mean it exists. So, what is required?

First, someone must be available to understand what’s happening in the work. At Company X the so-called ‘line leader’ worked the line full-time shoulder to shoulder with the team members. She had no time to grasp the condition of the line never mind respond to problems. She had to make production. For awareness to exist, someone must simply have time and space to observe the work.

Second, operators must have the authority, responsibility, and a mechanism to call for help. Assuming a job is designed as stable and repeatable, an operator should be able to tell when a problem has occurred that will keep them from achieving the plan. She must have permission and an immediate method to indicate a problem exists, thereby providing awareness to the team leader.

When a team leader writes, by hand, the actual production and problems on the Production Analysis Chart, that is a hourly demonstration to operators that she is aware of the current work condition. It is proof she is fulfilling the contract.

But awareness is not enough. In fact, awareness brings responsibility. For if the team leader is aware of problems and has the availability to take action, there is no longer an excuse to do nothing.

Management promises to solve problems when an operator cannot meet the plan

When an operator calls for help, a team leader is responsible for taking a couple different types of action. First, she must immediately intervene to help the operator return to a normal condition as quickly as possible. LEI refers to this as Type 1 problem solving. Successful intervention is not simple. Prerequisites include mastery of every work station for when the team leader must jump onto a job, as well as knowledge of the correct intervention to take.

A few years ago, LEI led a group of executives on a tour of a Toyota supplier in Japan. While observing an assembly cell we caused the operator to fall behind by asking him questions. We were a problem! As soon as we began to walk away, the team leader jumped into the cell to help the operator catchup. Both knew how to adjust their walk paths and their new work content was perfectly balanced. The team leader was aware of the problem, knew the correct intervention to take, and the job was designed to permit that intervention. It was not long before they had caught up to plan. I wonder if ‘Talkative visitors’ ever made it to the Production Analysis Chart….

Immediate intervention brings production back to plan. But a team leader is not just responsible for troubleshooting problems but eliminating the cause of problems. Problem solving is the vehicle for improved performance. Similarly, this is not a simple matter. A team leader must have problem solving skills, the authority to take action, and the resources to solve problems. This gets at the larger management structure that exists outside the production line. Can management effectively develop its people? Does management push responsibility down to the value-creating work? Does management provide support to solve problems?

LEI was fortunate to bring a group of its community members to Toyota Motor Kyushu last June (and we’ll return this June). As I recall, the Production Analysis Charts had a space for multiple stamps: the team leader’s and the group leader’s (in Japan, people use stamps rather than signatures). This points to the literalness of this social contract. The team leader not only captured production number and problems, but signed his name to demonstrate ownership: ‘I know what’s happening. These facts are accurate. I understand I am responsible for solving these problems.’ The group leader’s stamp was demonstration of how this social contract rolls up. The group leader’s stamp evidences he is equally aware of the problems, and is therefore, responsible for enabling the team leader to solve them.

Wrap Up

Let’s return to Mr. Yokoi’s question: “What exactly does management do here?” Even assuming stable production (which it was not), the team leader neither had awareness nor availability to grasp planned production versus actual production and the associated problems. The company was not meeting the terms of the contract.

Looking ahead, I think reflection on this question will grow ever more useful. Industry 4.0 promises the opportunity to capture real-time data to understand the precise condition of all sorts of things. But it also presents the risk of outsourcing management to machines, thereby absolving management of responsibility and tearing up the social contract that binds them together with workers.

As the numbers pour in, it is worth stopping to ask, “What exactly does management do here?”