Dear Gemba Coach,

How do you handle it when you find out you’ve been wrong; when you’ve advised people to do something that you later discovered wasn’t right?

I kick myself – and tell them. It’s never easy, but if you’ve been working with people long enough they understand that you’re not all knowing and that the journey of the discovery works both ways – you learn as they do.

My biggest, latest mistake was on obeya rooms. I’ve been setting up obeya rooms to encourage management teamwork for a decade, and been writing about this for almost as long. When obeyas started to appear in engineering, they were mostly extended plans visualized on the wall. Useful, but not earth shattering.

What I was doing at the time was a main wall with an indicator, such as quality, or inventory, and then the relevant A3s underneath to show the team they were collectively working. Something that would look like:

Courtesy of N. Dubost, Thales

Management teams kept telling me this was an awkward format, but I didn’t know what else to do – it did produce better teamwork and I felt we needed to stick with it until it became part of the culture.

Oops

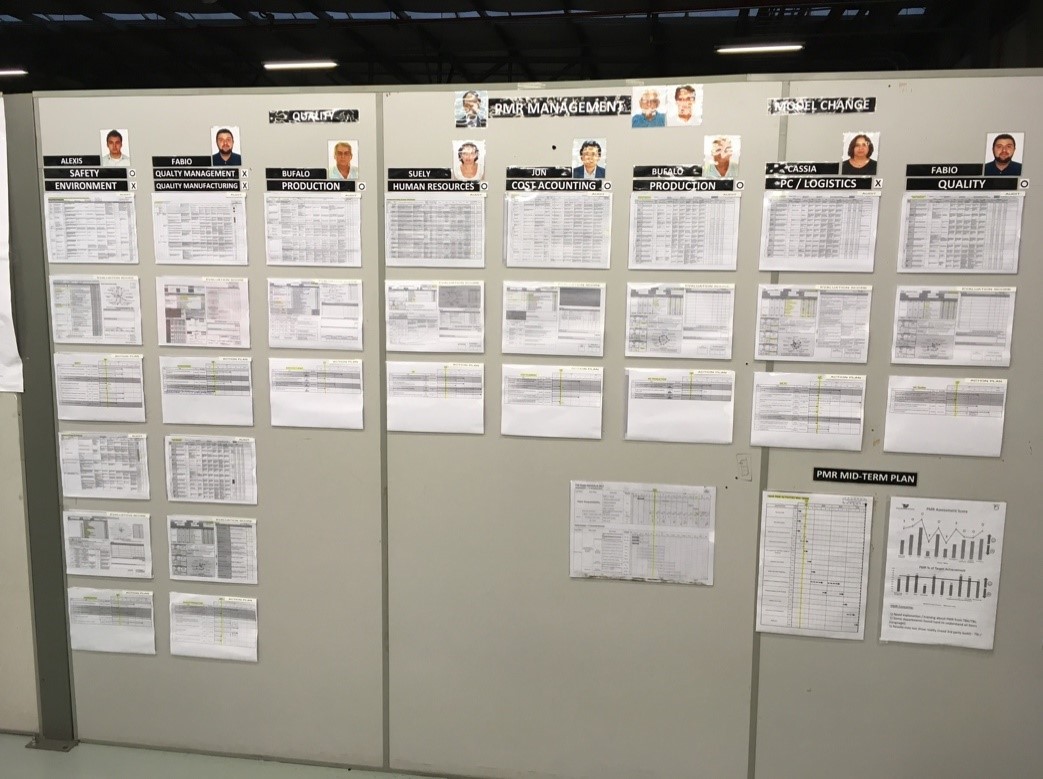

Then, a few years ago, I visited a Toyota Boshoku supplier plant in Brazil, and saw a different format:

Courtesy of Boshoku Brasil

And:

Courtesy of Boshoku Brasil

What struck me was that the presentation was definitely by function – even though functions could participate in solving generic problems, such as quality or model change and so on.

It had been bugging me for a while, and I kept encouraging management teams to set up obeyas in the old indicator driven way until I read more about the origins of the obeya. The origin story is well known, and I had heard it right from the start when I started obeyas. Takeshi Uchiyamada, the story goes, was appointed chief engineer of the first-generation Prius and felt overwhelmed by all the different technologies he had to fit in the car. He felt he did not have enough authority to make key decisions in front of very experienced disciplined leaders, and so set up a “large room,” an obeya, for collective decision making. This worked so well Toyota made it a standard of its Toyota Production Development System. With its indicators and A3s.

I have argued for a while that obeyas are not about project management but product understanding. Even so, I missed the fundamental purpose of the original Prius obeya: meshing technologies.

The project-management bias is so deeply ingrained that it is hard to escape, even when you try to do so. Obeya is not about visualizing our cross-function efforts. On the contrary – it’s about displaying our functional efforts to each other so that we can understand what each other are doing and come up with better decisions together. The deeper insight is that:

- At a product level, we need to mesh technologies together to offer a great product

- At a business level, we need to mesh the systems together to deliver more value

Great products are the outcome of how well we mesh technologies together (the “hat” of the QFD matix). Great companies are the result of how well we mesh systems together.

Bite the Bullet

Consequently, obeyas look very different in form and spirit. They visualize the old results/process framework in terms of clear qualitative business results (safety, quality, flexibility, productivity, etc.) from repeatable methods, to processes in terms of technical “how-tos”. One wall for indicators of various kinds, and the rest process points that need explaining system by system or tech by tech in terms of next steps, problems encountered and explaining what we’re trying to do in order to clarify interfaces. APIs in modern parlance.

Courtesy of B. Evesque, SNCF

Yes, it’s tricky. I’ve pushed people to do one thing, and now have to go back and say, “Sorry, I know I insisted on this but I was wrong and we need to change it.” Well, it’s a question of biting the bullet. If the argument is strong, they’ll accept it, and you’ll get a healthy dose of ribbing.