(During The Way to Lean, a free webinar on the “lean trilogy” approach to deeply understanding and applying kaizen daily, we received more questions than presenter Michael Ballé could answer during the Q&A session. Michael is answering them, including the question below, in his Gemba Coach column -Ed.)

Dear Gemba Coach,

What does “separating human work from machine work” mean? How does it matter?

Agreed, the phrase is a mouthful, but “separate humans work from machine work” is nevertheless a key aspect of lean’s “jidoka” principle and a deep source of productivity and quality. Most people are familiar with the “just-in-time” dimension of lean, but the “jidoka” aspect is the hidden part of the iceberg – where the real potential lies.

“Stop and report abnormalities” is rarely practiced, but becomes better known as people intuitively see the sense of it. Rather than build the wrong thing or put it aside to continue to work as if nothing happened makes intuitive sense. Similarly, “mistake-proofing,” coming up with practical devices to reveal not-OK work on the spot is not always easy to do, but easy to understand.

Separating human work from machine work is less familiar, and still a huge source of quality, productivity, and cost reduction. I was on the gemba the other day watching operators assemble factory equipment. As part of the assembly work, they have to cut steel tubes. The operator uses a very simple steel cutting machine: he positions the bar, then lowers the saw on the bar, stops when the tube is cut, stops the machine and picks up the parts. The operator is part of the process – he cannot move on and do something else, so he is tied to the machine. As a result, you need both a machine and a man to do the job.

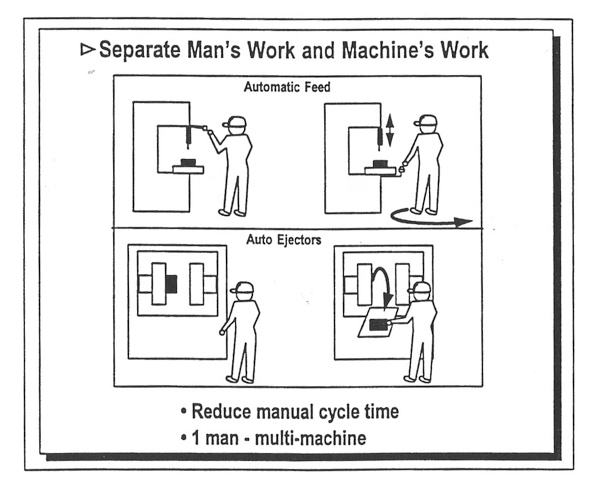

Separating human work from machine work would mean figuring out how to (1) place the part in the machine, (2) touch a “go” button, (3) move on and let the machine operate, and (4) come back later to pick up the part when needed. This involves two basic engineering tricks, as shown here in old Toyota documents:

- Automatic feed: once you place the part, the machine picks it up by itself.

- Autoeject: when the machining is done, the part is ejected so it can be picked up easily.

In other words, imagine you’re cooking a meal on a stove – you’ve got several pans simmering which you need to keep a constant eye on in order to get the dish just right. On the other hand, if you place a meal in the microwave, you press the button and move on to do something else – answer emails or wash the dishes. When the microwave is done, it pings to let you know, and you can come and pick up your dish when it’s convenient. Granted, it takes the fun out of cooking and a hand cooked meal might taste better, but that’s a matter of tech improvement. The point is that the microwave liberates you from having to babysit it through the process, so you can do something else.

Substitute “System” for “Machine”

Many jobs are service related now and you might think: What has this got to do with me; how likely am I to find myself pressing two buttons on a machine to watch it operate? Quite likely, in fact, if you switch the word “system” for “machine.” Think of the number of times you’ve got to babysit a request through any system because you know that if you don’t, the response will never come.

In logistics, separating human work from “system” work means that you get all the right parts and information when you need them, how you need them, and in the quantity you need them as opposed to have to do some work to drag the information or part you need out of the system. Administration is even worse: when have you found admin working for you as opposed to them asking you to work for them?

Many lean students feel they’ve got enough on their plate with understanding flow and that they will get around with more “advanced” principles such as jidoka later on in their lean journey – but they miss the point. Lean is a system, which means that you can’t progress on one dimension without also moving forward on another. For instance, creating continuous flow is one of the key aims of lean as it both increases quality and productivity while reducing lead-time. Continuous flow is often hard because of monument processes, machines, or systems that are centralized and thus create batching.

These “monument” processes often require a lot of care and need people dedicated just to keep them running. In order to make a step further towards continuous flow one needs to:

- Separate the people from the machine by making the machine more autonomous.

- Reduce and simplify the process until it fits in the continuous flow.

In many ways, this has been the story of computers – from centralized card-run mainframes, to mini-computers on people’s desks, to movable laptops to smart phones. None of this is possible without making the process, much, much easier to run.

Tips for Starting

Where do we start? Well, you wouldn’t stand watching your dishwasher cycle would you? Good opportunities for kaizen are:

- Is someone watching a process output in case some parts or product come out wrong?

- After pressing a start button, do you have to stand there to make sure it goes properly?

- Are people holding the part in the machine, or need to adjust the position for the work to be done right?

- Does the machine eject the parts independently so that you can pick them up easy to move on with the next step? (think of vending machines who do eject parts, but then you have to struggle with the flap to get the stuff you bought out.)

Practicing separation of human work and machine (or system) work at every opportunity will progressively change how you look at technical processes and pave the way for brand new insights on machine design – and process efficiency. The ultimate goal of jidoka is to guarantee continuous substance transformation, and the full realization of flow.